|

Abstract The last few decades have marked a glorious period of demographic transition in Karnataka, especially marked by considerable decline in both fertility and mortality rates. According to the 2011 Census, the state has a population of 6, 11, 30, and 704 with a decadal population growth rate of 15.67 per cent as against 17.64 per cent for the country. It was 17.51 per cent as against 21.54 per cent for the country in 2001. As compared to the other states, Karnataka state has already achieved the replacement level fertility by 2006 itself (TFR 2.0 & Replacement level fertility was 2.1). As per the 2011 censuses, Karnataka has a better position in terms of sex ratio i.e., number of females per 1,000 males (965) as compared to the national average (933). During the last century, the sex ratio was adverse to the women and continued to be so. In 1891, there were 991 females per 1,000 males. But a century later, the sex ratio had substantially declined over the period to 960. The progress of health care and its utilization has fully supported to achieve the life expectancy at birth of women that is higher than the men and the male-female gap is widening in favour of females. Age at marriage is an important indicator to understand the levels and trends of population growth and it plays a key role in limiting the family size. It is also considered as one of the best indicators for studying the status of women in the developing countries (Vagliani, 1980). The fertility transition has been further faster in the south resulting in widening the gap in fertility between northern and southern districts and between rural and urban areas. The percentage of contraceptive use among currently married women in the state has increased from 58 per cent in NFHS – II to 64 per cent in NFHS – III. It is also much higher (64 per cent) than the national average (56 per cent). This paper argues that demographic transition has helped women to get into employment and therefore achieve empowerment, because women’s increasing employment is influenced by their changing demographic profile. This is in terms of better access to health, nutrition, marriage at proper age (not child marriages), small family norm and economic and social empowerment, to mention a few. Women’s health has undergone substantial changes for the better. Yet, in many cases, women lag behind due to illiteracy and lack of better opportunities to work and income. The concept service sector is very vast and there are wide gaps in women’s access to better economic opportunities and empowerment although there are better options wide open. Social inequality based on caste, class, region and skill formation besides continued gender based oppression are the causes behind this continued backwardness of women despite support from a positively changing demographic situation in Karnataka. It calls for appropriate policy intervention and public debate and participatory action. Introduction Ever since the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were set up, empowerment of women has gained additional emphasis. Importantly, there is a shift in the realization from viewing women’s problems purely from a gender perspective to being viewed as a basic human right, and also as lying at the heart of developmental efforts to achieve these goals. Even at the global level, obstacles faced by all countries, irrespective of their level of development, are the widespread prevalence of gender discrimination, violence against women - at home, work place and in the public places and continued patriarchal dominance (UNDP, 2009). Many studies have argued that such gender based disparities are at the root of stagnation and overall development. In the Indian context, women largely suffer from two major handicaps, viz: • they are illiteracy; and • low work participation rates. Because of the above these two reasons, women are deprived of control over assets, personal security and participation in political processes. However, data on demographic indicators for women suggest that there is a positive change in this respect, where, due to incessant efforts by the government, there is a decline in fertility, over the years, leading to demographic transition in the country. This positive improvement has enabled certain long- standing and remarkable achievements for women, such as their economic empowerment caused by their role in productive economic activities. Women’s Health and Economic Empowerment A positive side of women’s status in India and in the state is that thanks to the concerted efforts of the government, the health status of women has seen significant betterment in the recent decades as compared to the earlier years. The health status of women is generally measured from the point of view of their life-cycle stages occurring in them. For example, ages 0-6 are very delicate and susceptible to childhood diseases causing infant mortality. Discrimination in nutrition levels, care and facilities for basic hygiene, etc., affect the genders differently. Girls from poor families are often deprived of and marginalized in accessing the above. Second age category of 6-15 or 17 is of growing up where many of the earlier stage’s deprivations continue to haunt young girls and make them very susceptible to anemia and other deficiencies. Further, 15-49 years in their life are critical years as they mark the reproductive stage or phase, when a woman is exposed to much physical strain and requires a lot of nutrition and attentive health care practices. ‘In general, women suffer adverse health outcomes such as higher mortality and morbidity at stages in their life-cycle when they are biologically and socially vulnerable such as during their peak reproductive years and during early childhood’ (Syamala, 2013). But in their old age, ‘women have an advantage in health outcomes over men in the later stages in life reflecting in lower mortality rates’ (ibid). As maternal mortality rate (MMR) is generally used as an indicator of maternal health, and well being, even a slight improvement in that standard MMR1 is taken as a positive improvement. For a long time, the data indicated high levels of mortality of women caused by childbirth casualties or death occurring during childbirth. It continues to be an important indication of women’s low status in the country (It is 212 deaths per 1000 deliveries, thus making India as a country with continued highest levels of MMR in the world (ibid). Women’s Improved Health and Her Labour Force Participation An interesting phenomenon that has occurred in the recent decades is also about the increased labour force participation of women across countries of the world, even including the backward regions such as Africa. With increasing demands on economic needs and consumerism, women are accepted to be stepping out of homes into the public sphere and accepting roles in the service sector, business, trade, professions, and so on, just as men have been involved in these activities since long. There is almost no economic activity that is left out of reach of women. This has been made possible with increasing access of women to migration to cities and towns. There has been a tremendous change in the gender roles of women and men. The traditional roles of women have almost collapsed especially in the urban areas. They have stepped into a number of economic activities, both in the informal and formal sectors. Gender gap has more or less reduced and vanished depending upon the type of activity and place of residence, urban or rural. This transformation has also come to affect the existing pattern of gender division of labour and gender relations in the work and family spheres, in both rural and urban areas. What is important from the point of view of the present paper is an interesting turn of events caused by the above-discussed positive impact of health reforms on women in many countries. It refers to the rising or already well established higher growth in labour force participation by women. Not just this, but the improvement in health of women and the decrease in the burden of child bearing and resultant child rearing practices that used to consume a whole of their time and energy, have also led to women having an upper hand in their participation in the labour market often to a much greater extent than men. In other words, low fertility is linked to increased labour force participation in both the developing and developed countries. India is not lagging behind this trend. Even here, studies and NFHS have reported that fertility is declining over the years leading to a rise in women’s employment potential shown in their increased labour force participation rates. What is more: India is fast approaching the international norm of “2 child” in this respect. However, unlike other countries, the decline is unfortunately not resulting in increased labour force participation by women. This is a sad situation as the low fertility in India is not matching with the international trend of “2 child” and it is more perplexing to note that the mismatch between low fertility and high or improved labour force participation is more glaring in the case of urban India, i.e., cities and towns. In fact, the improvement should have reflected itself better in the cities and towns. With the above background, the paper considers the twin issues of fertility transition in Karnataka and the increased participation of women in the service sector as being interlinked. The National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) data used here is based on the comprehensive surveys of Employment and Unemployment rates and is brought out once in every 5 years. The study has shown that (using the NSSO data) the participation rate of women in labour force has to be viewed for analytical purposes from the perspective of sectors of work also. The table below shows that the Labour Force Participation Rates (LFPR) are in fact much higher than the All India figures! This is for both Males and Females and it is also true of both rural and urban. Female Child Labour While the demographic transition has resulted in increasing work participation by women particularly in the wage labour type of activities, sadly we also notice the presence of a high rate of female child labour among the households of these women. Thus, the greener side of fertility transition is blurred by the rising female child labour incidence. The improvement in controlling fertility seems to have not been used completely for women’s emancipation as poverty has continued to affect women’s lives by pushing the girls to work, rather than enabling their continuation in the school. Even the programmes like “Sarva Shiksha Abhyan” are of little help here. Data shows that female child labour in the state, unfortunately, is higher than the national average. For example, 24 out of every 1000 workers are child labourers here, making the situation highest among the neighbouring states of Karnataka (refer to the table below). Further analysis of data has disclosed that in the villages of the state, child labour is quite high not only among the female children but also among boys. But when we come to the towns and cities of the state, there is a different trend where both male and female child labour is found; although it is seemingly high for boys. This does not mean that the girls are in schools in the urban areas. It only suggests that due to poverty of the household, girl children are denied education and are kept in the house to take care of domestic work and/or caring for younger siblings. This situation is quite true especially among the households belonging to lower economic strata where both the parents are at work. Work Participation Rates across Age Groups A significant contribution of declining demographic rate or fertility rate is the increasing work participation rate for women in different age groups. For example, it is not so well established in younger age groups leading to the conclusion that girls are allowed now-a-days to seek education, at least to a minimum level or primary or higher primary. The reforms introduced by the government and through programmes like “Sarva Shiksha Abhyan” are relevant to be noted here. Tables 3 and 4 show that there is a decline in WPRs for younger age groups and substantial increase for the older age groups. This is a very good sign especially in the school going age group, indicating the importance of female education and more so in urban regions. Work Participation Rates and Household Income It is further seen that decline in fertility rate and the resultant increase in work participation rate have a link to household (HH) income and empowerment of women in the HH. Women are increasingly getting into service sector jobs due to the free time available to them. Data shows that due to freedom from pregnancy and additional child care duties, women, particularly in rural areas, are able to be engaged in work. According to a state government study carried out at ISEC, 57 per cent of rural women are engaged in some or the other form of work. Educated women have taken up work in the formal sector like small industries. They also often commute to nearby towns and cities as teachers, garment workers, etc. Rural – Urban Differentials Despite the betterment in female fertility rate towards a decline, the work participation rates in for women show a reverse trend as far as rural and urban areas in the state are concerned. For example, it is found to be high among poor households. Only a few women are able to remain outside the work pattern. Forced by economic hardships at home women are pushed into employment, regardless of other responsibilities. Women from high income brackets and those from middle income groups are far less in employment categories. This is particularly true of the rural areas where non availability of work and patriarchal social norms and rigid cultural patterns are stated to be the causes of reduced work participation by women. Participation of Women in Service Sector across Social Groups As noted already, women from the weaker sections of society and from low castes are also those with the highest participation in the lower levels of service sector activities. Agriculture has the largest segment of working women (84 per cent) and 86 per cent of them are from the SC group. Women from the general category are employed in agriculture up to 75 per cent. Participation in non-farm employment is restricted to women from higher income groups. As far as employment in the service sector like garments, urban jobs in offices, self employment, professions like nurses, teachers, tailors, petty traders etc are restricted to the women who are educated and residing in urban areas among the socially backward classes. On the contrary for the general group the line was more flat. High WPR and low level of education among the socially deprived class implied low skilled jobs characterised with low pay, tedious and long hours of working. This calls for programmes towards skill development among the socially deprived class. WPR is quite high with respect to deprived classes in both rural and urban areas. Work Participation Rates across Education Group Women from rural areas have a deeper decline in employment than those in urban areas. The pattern of women’s empowerment is closely related to their educational achievements and employment. Service sector jobs are varied in terms of their income returns. Higher the education of women, higher is also the rate of unemployment. There is also a wide gap between unemployment by the illiterate and their jobs in the service sector and that of the educated unemployed women (50:104 in rural and urban areas respectively). There is a trend towards taking up jobs in the industrial sector by women in urban areas. Manufacturing is a major sector here followed by education. In the latter, there are a high proportion of teachers, which is opted by most of the women. However, due to a period of recession and economic fall, manufacturing sector faced a downward trend from 2004-05. The sector has somehow regained its original position by 2009-10. At present, the share of manufacturing in the overall rate of women’s employment is 30 per cent. Rural areas continue to have a large share of female work participation in agriculture as marginal workers. Rural areas have continued to have a marginal decline in the share of agricultural workers. Agricultural worker continues to be dominant category among females. Not much replacement of labour has taken place in rural areas with respect to female work participation.

A happy trend is that from 2009 onwards, nearly 44 per cent of female work force is in regular employment. This has provided better job security to women and has enabled improvement in their overall socio-economic status also. The contribution of fertility transition is substantial in this regard. District wise Situational Analysis Lastly, the paper presents the wide variation observed in the work participation rates across districts. Variation is much higher in urban areas (39 per cent) than in the rural (30 per cent). Women were not found unemployed in any district but for Gulbarga and Bellary which have shown high unemployment rates in their rural pockets. On the contrary, the urban areas have shown increasing participation by women in various types of service sector activities. The north Karnataka districts are not only those with high poverty but they are also highly backward with low agricultural productivity caused by poor irrigation and dry lands. It is distress that has pushed women to take up whatever comes their way. Many have migrated to southern areas looking for wage labour. Districts with low work participation rates point towards not unpreparedness of women to work but of non availability of work. Conclusions The paper has discussed a few trends in work participation by women in rural and urban Karnataka chiefly influenced by declining fertility rate. It has also discussed the various facilitating factors promoting greater participation in work by women. Women from lower castes and classes are more into blue collar service sector activities and for low wages and uncertain jobs with no security – personal or financial. The districts in the north are more affected by the negative growth caused by economic instability. True to feminisation of poverty, the brunt of the problem is faced by women. Women in urban areas are much better in their work and social status as they have taken up employment in relatively better sectors. The advantage is high for these women if they are also literate or educated. The situation could be improved by the Government paying special attention towards specific policy to encourage more and more women to get into employment that in the long run promotes their empowerment. Further, the paper recommends also that the Skill Commission set up by the Central Government as part of the 11th Five Year Plan, by the Planning Commission, in 2009 can take up measures to improve the situation of women’s economic empowerment. On job training and capacity building has taken place already under this skill development programme. So far about 3.5 lakh persons have been trained in various trades. The decline in fertility can be usefully utilized by the State Government only when it evolves proper channels for empowering women in the state. References

Dr. M. Lingaraju Faculty, Centre for Human Resources Development, Institute for Social & Economic Change, Nagarbhavi Bangalore 72. |

Categories

All

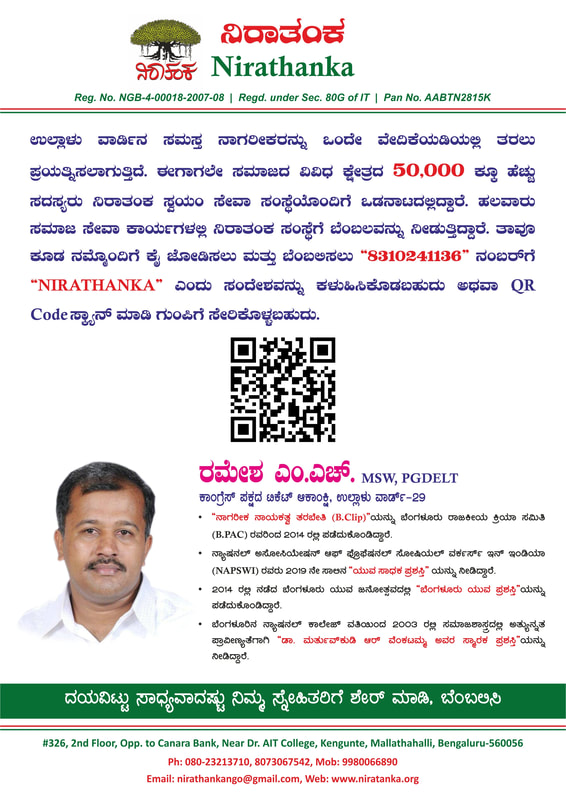

Social Work Learning Academy50,000 HR PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS. MHR LEARNING ACADEMYGet it on Google Play store

|

SITE MAP

SiteTRAININGJOB |

HR SERVICESOTHER SERVICESnIRATHANKA CITIZENS CONNECT |

NIRATHANKAPOSHOUR OTHER WEBSITESSubscribe |

MHR LEARNING ACADEMY

50,000 HR AND SOCIAL WORK PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed