|

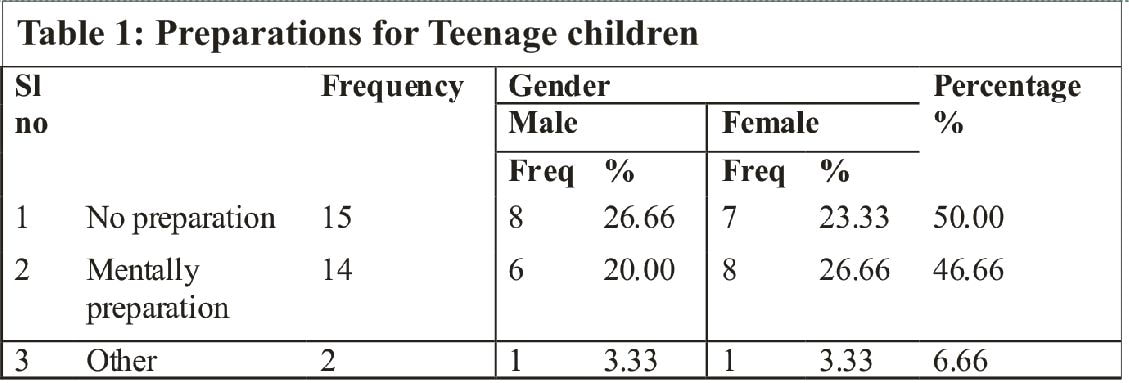

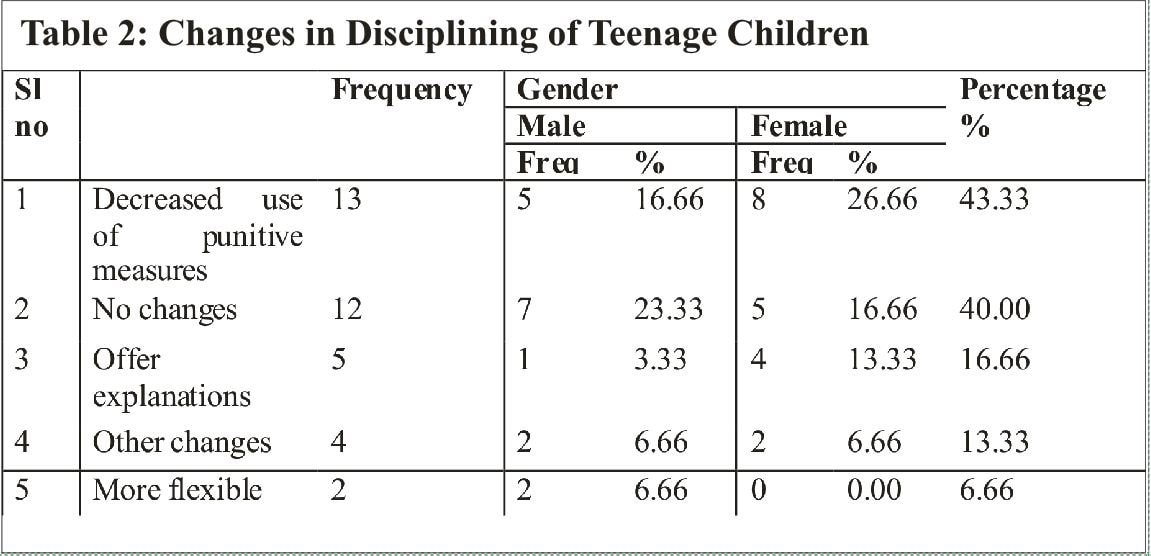

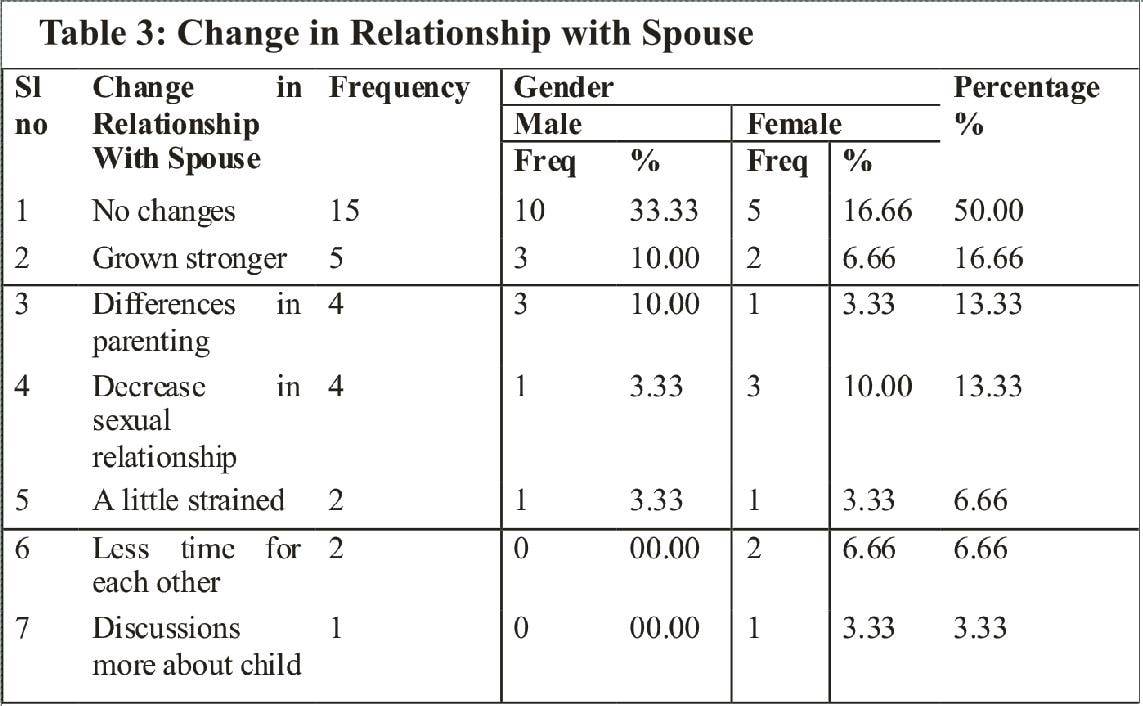

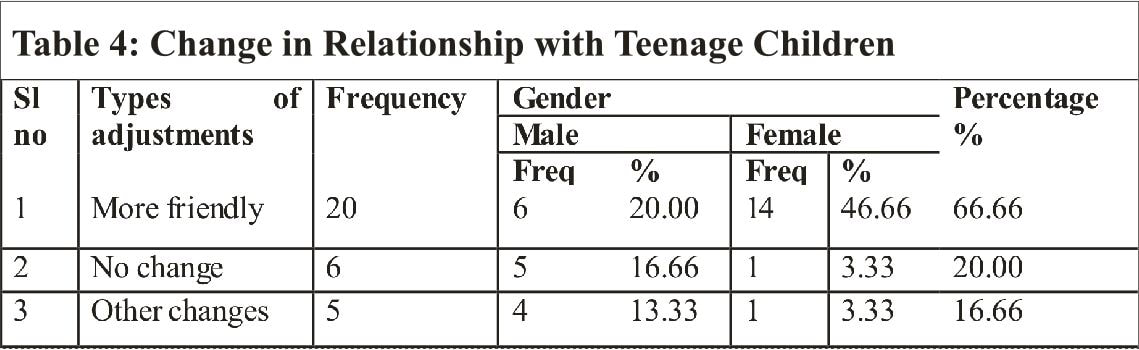

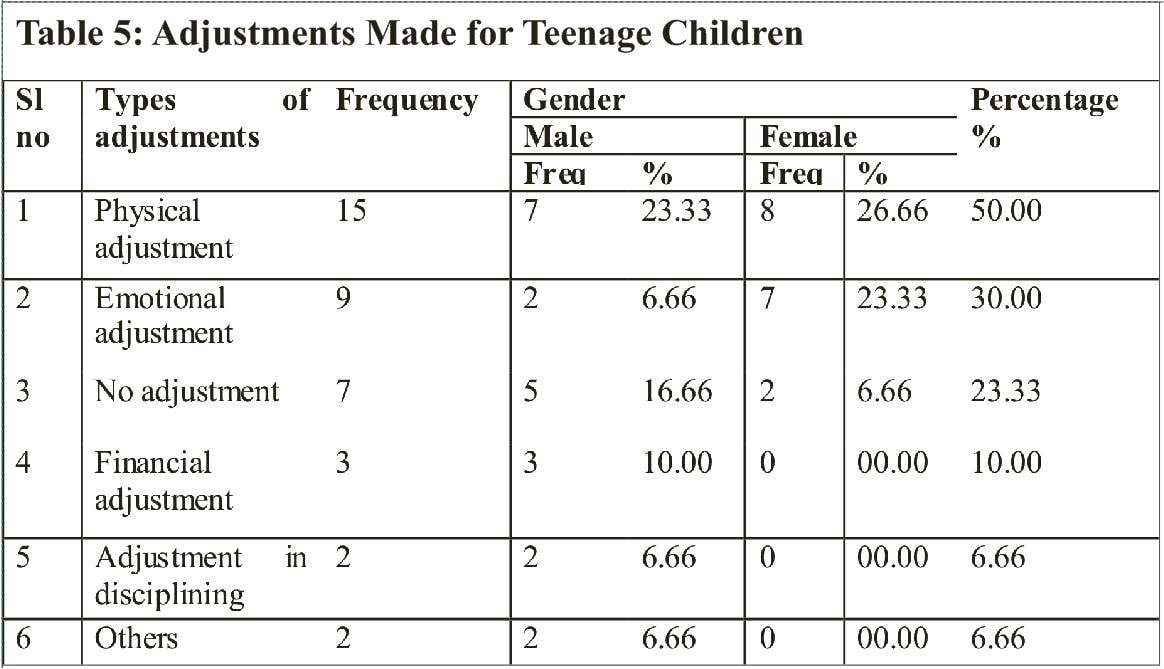

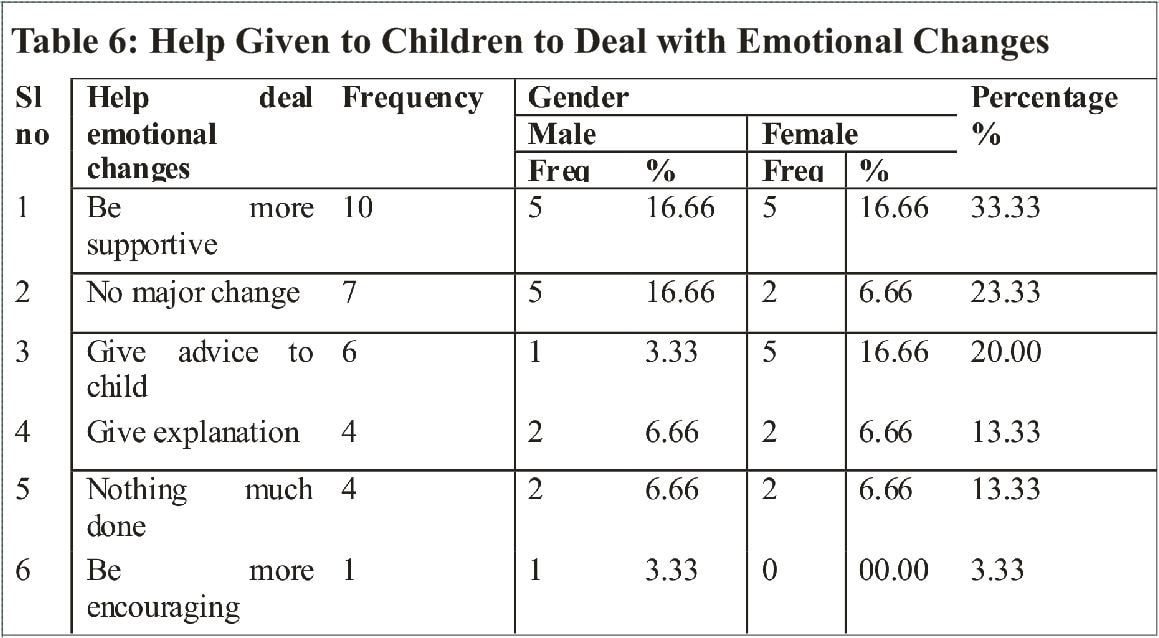

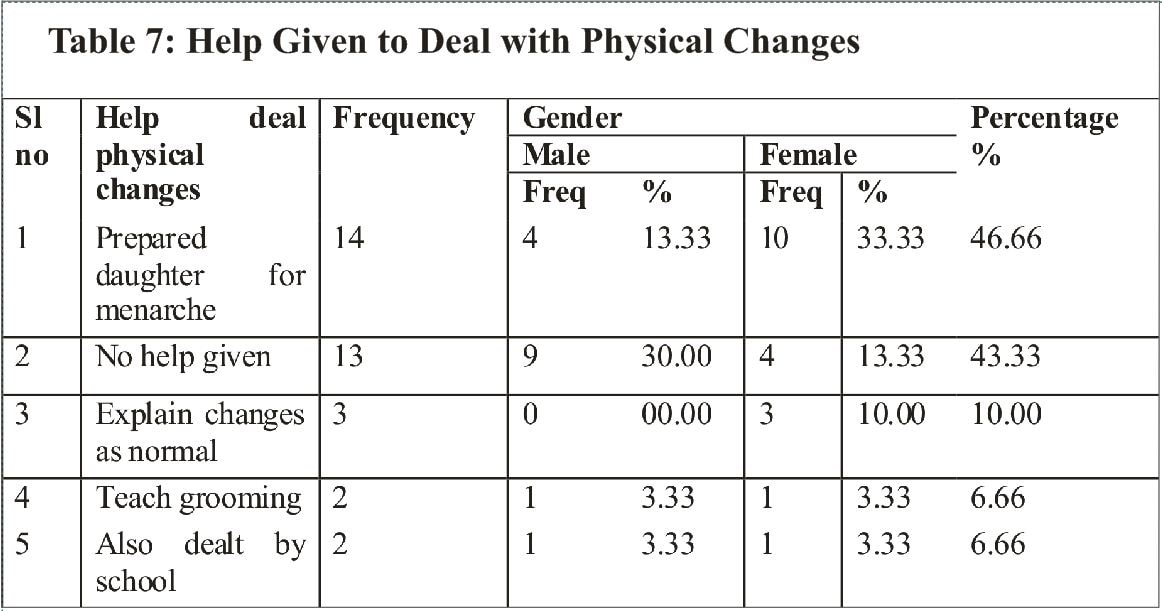

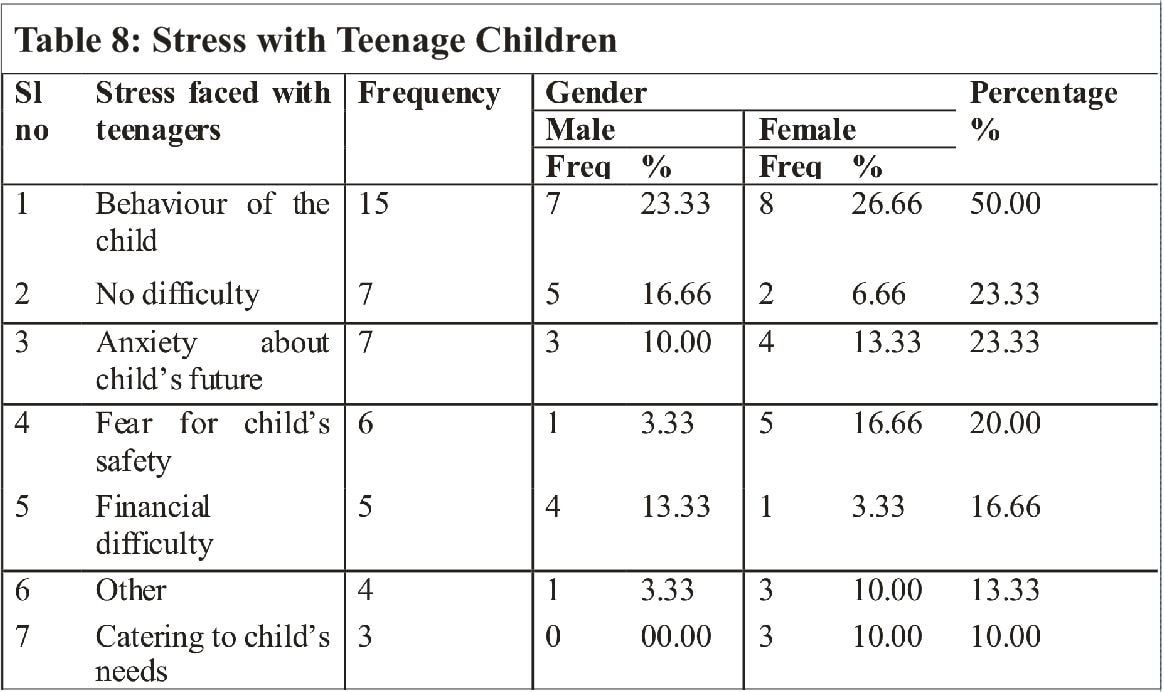

Abstract: A qualitative inquiry was carried out on thirty respondents who had adolescent children to understand the life cycle tasks of families with adolescents. It was seen that most of the parents of adolescents have to undergo changes in relationships with spouse and children and had to make various adjustments in their lives in order to accommodate the needs of adolescents. This article also looks at the ways in which parents handle the stress of having a teenage child at home and briefly discusses the implication for parental counselling. Introduction A family developmental perspective is considered crucial to understand family health and dysfunction and their relationships to individual symptomatology. The families are considered to be going through a periodic family transition of a crisis nature that necessitates structural change with in the family (Lewis, 1988). Going through these transitions also involve restructuring and taking over new roles and tasks. Parenting is one such role that couples assume upon the arrival of a child. As the child grows the tasks of the parents undergo changes and challenges. Parenting adolescents is said to be one of the most trying stages in the family developmental life cycles. Understanding the tasks of families with adolescents can help prepare parents and adolescents go through this transition with lesser turbulence and more understanding. This paper attempts to bring an understanding of the tasks in parenting adolescence and looks at the implications of the same in counselling. Review of Literature According to Pipher (1994), parents who are in control and high in acceptance, have adolescents who are independent, socially responsible and confident. Henry and Peterson (1995) found that adolescents tend to do better in a family where parents have rational control and ultimately decide what is appropriate. The important issue in this stage is for the parents to focus less on the adolescent’s problems and pay more attention to themselves and their own relationship (Carter and Peters, 1997). Preto (1999) suggests that the families with adolescents need to make adaptations in their family structure and organization in order to handle the tasks of adolescence. In doing so, the family is transformed from a unit that protects and nurtures a young child to one that is a preparation center from which an adolescent enters into the world of responsibilities and commitment. After a course of confusion and disruption, parents are able to change their rules and limits and reorganise themselves to allow adolescents more autonomy and independence. This life cycle stage is one in which the sets of generation renegotiate roles. Parents and grandparents are also seen to redefine their relationship and spouses renegotiate their marriage and siblings to question their position in the family. Some times the demands in the re negotiation are so strong that they can reactivate conflicts between parents and grandparents or between the parents themselves. When compelled to make changes in themselves, and experience acute dissatisfaction, then the normal stress and tension that comes with this lifecycle stage becomes exacerbated. This stage indicates a change in the relationship in which there is more closeness. This often results in difficulty for parents in disciplining their children. Dankoski (2001) also further states that the teens can also be strong triangulators of their parents. This affects the closeness in their relationship by splitting them or detouring the focus from their relationship. There could be conflicts and power struggle in their own relationship that can affect their ability to accept their adolescents’ increased independence. The increased autonomy in adolescents could be a feeling of fear for the parents. Hence, they need to make a shift in the bond between parent and child. Parents are found to be less providing less support to adolescents regarding biological and physiological changes they experience. Sexuality is another important aspect in which there is little parental input. This creates a situation where adolescents turn to peers and other sources of information (Abraham 2000; Abraham & Deshpande 2001; Sachdev 1998; Murthy 1993). Verma and Saraswathi (2002) have found that competencies and coping styles between parents and adolescents are a source of anxiety and stress both for adolescents and parents. Parents themselves appear ill prepared to cope with social change, having grown up in hierarchically structured and interlinked social and caste groups that provided stability (Singhal & Misra 1994). Describing the importance of family relationships among adolescents and young adults Kaye et al (2008) have found that parent-marital quality combined with parent-adolescent relationship quality are related to physical health, mental health, substance use, sexual activity, and religious activity outcomes during middle adolescence and, to a lesser extent, early adulthood. Further they have also stated that adolescents who have troubled relationships with both parents, poor parental marital quality tend to be at a greater risk for negative well-being outcomes. They tend to have substance use and poor health among other outcomes. Cui and Donnellan (2009) have demonstrated that marital satisfaction decreased over time for parents with adolescent children. The increases or decreases in parental conflicts were over raising of children and this is was associated with changes in the marital satisfaction for both mothers and fathers. Several studies (Patterson and Kavanagh 1992; Moitra, & Mukherjee, 2010; Okorodudu, 2010) have observed that parenting plays has an influencing role in adolescent delinquent behaviour. These studies indicate that adolescence is a period of potential turbulence for families and handling of the changes and needs of this period is a very important task for parents undergoing this transition. Methodology This was a qualitative, exploratory research. The aims and objectives of this study were to understand the tasks of family with adolescent children, stress faced and coping with stress. 30 respondents were selected for the purpose of the study using snowball sampling technique The researcher first identified a local person as the key resource person, who has a 12 years experience in working with the local community. The sample was described to her. Researcher was introduced to the respondents who agreed to participate in the study. Informed consent was sought from them. These respondents in turn introduced other respondents who fit into the same description. And they in turn assisted the researcher to identify other respondents. 30 respondents were recruited to this study through the above said procedure. In order to get the male- female perspective, efforts were made to recruit equal number of female and male respondents. Data was collected using a Semi-structured interview schedule (prepared for the study) Table 1 depicts the different ways in which the respondents prepared themselves for bringing up teenage children. A qualitative analysis of the data revealed that 50% respondents had not prepared in any way for the problems associated with teenage. Some of the reasons given were that they had not done any particular preparation as they had not thought about it and were prepared for the second child who was going to enter teenage. For example, one person said, “ Where is the time to think about all these.” Another respondent said, “ no, but I would be preparing when my daughter comes to the age, because we have other problems when a girl comes of age. For that I am naturally preparing now, because my daughter is 10 years. For my sons I did not.” Yet another person said, “ no, we haven’t thought about it.” Around forty seven percent (46.66%) respondents reported that they had mentally prepared for bringing up teenage children. This included reading about teenage, discussing about how to bring them up and anticipating the problems associated with teenage. The following are some of the examples to illustrate the same. Quotation 1: “ I thought of my teenage how we were prepared! We were not given much attention and I was feeling lost. I was thinking that my children should be prepared mentally and physically for the changes and I stared reading up on all these.” Quotation 2: “ I discussed with wife regarding how to bring up the child, freedom to be given etc, and at times we would discuss with others who have gone through this stage for some guidelines and read magazines.” Quotation 3: “We anticipated that as they get into their teens they will have their own lives rather than mix with you; they would be with their friends and you become the older generation.” The other preparations involved financial preparation and distancing physically from children. Table 2 illustrates the changes made by the respondents in order to discipline their teenage children. A qualitative analysis of the data revealed that the majority of the respondents (60%) had made changes in the disciplining of the children. Out of them 43.33% reported decreased use of punitive measures like beating the child as a change in their disciplining pattern. The following are some of the examples for the same. Quotation 1: “I don’t beat him any more” Quotation 2: “Before I used to beat them a lot, drop hot wax from the candle on their hands. Now I have stopped all that.” Quotation 3: “I try not to be very harsh with her.” Forty percent reported no changes in the disciplining pattern. Some of the reasons given were that the children were obedient and that they (children) have made the changes themselves. For example, one person said, “ more or less it is the same pattern. We always try to justify our action.” Another respondent said, “even now they follow their routine, and listen to what we say.” Yet another person described, “ No changes. It has been the same. They have changed. They have accepted all changes.” About seventeen percent (16.66%) had resorted to giving more explanations and advice to children. For example, one respondent said, “ I have stopped beating them. I just tell them what is good for them to do and what is not.” According to another respondent, “we now explain things to her and tell her things in a serious manner.” Two respondents became more flexible. For example one respondent said, “we have become more lenient to her, we can’t stop her from talking to her male friends. We have to be more flexible with time and generally leave her alone.” The other changes included increased verbal reprimands, treating adolescent as equal, and non-interference. Table 3 depicts the changes that took place in the respondents’ relationship with spouse as children reached adolescence. A qualitative analysis of the data revealed that 50% reported no changes where as the other 50% respondents experienced some changes in the relationship with their spouse. About seventeen percent (16.66%) of respondents reported a stronger and closer relationship. For example, one person said, “our relationship has only grown stronger.” Another respondent said, “ we have become emotionally closer to each other and he gives me a lot of advice and help.” Around thirteen (13.33%) reported differences with spouse on issues like parenting and disciplining. According to one of them, “we started having differences of opinion in how to bring up and in dealing with children. She prefers to use physical punishment whereas I don’t.” Another respondent explained, “Both of us have different ways of thinking regarding children. I try to make him (husband) understand that he needs to be less harsh on them.” 13.33% respondents reported a change in the sexual relationship. This included less frequent sexual intercourse and being more careful when children are around. For example, one respondent said, “we control ourselves more than before now as the children are growing up and they understand these things.” According to another respondent, “ we are not sexually that active, we are careful.” 6.66% respondents reported a strain in the relationship. For one of them it was not due to the child while for another it was because of the teenage child. According to one of them, “it is a little strained now. When wife has an argument with the daughter, she takes it out on me. This causes some tension in me but I try to understand and keep silent.” The other person said, “our relationship is not so good but it is not because of the daughter.” Having lesser time for each other was another change reported by 6.66% respondents. The respondent described, “I think children are more important than husband. I give more time to them as they need more attention, so I have less time for my husband.” One respondent reported that discussions between the spouse and her more about child centered. According to her, “now there is more talk about how husband should be with the son, how to deal with him, his future etc, other wise no changes.” Table 5 shows the change in the relationship with children as the children reached adolescence. A qualitative analysis of the data revealed that a majority (66.66%) of the respondents experienced changes in their relationship with their teenage children. The major change reported was that of having more friendly relationship with the child. This included being more friendly, having better communication and a more sharing relationship. The following are some of the examples for the same. Quotation 1: “we are more friendly- we are like friends, I reciprocate according to their age only.” Quotation 2: “I am still their parent, I tell them I am still your mother not friend so you have to talk and behave like that, which they hardly do. I talk with them matters that I could not talk when they were children, they are more like my confidantes. I tell them my emotions. When they are children it will be burdensome for them, but at 17 you can tell them exactly what you feel.” Quotation 3: “In a friendly way. When they are young it is more of a motherly feeling, now it is that of a friend, you can’t be bossy.” Quotation 4: “ I cannot say that they are children, I have to be like a friend to them.” Quotation 5: “there is some change in the relationship with my son. If I don’t wear matching clothes then immediately, he will tell what sort of clothes match. Now he feels that I should not be shabbily dressed- we are more like friends- sometimes I ask him or take his opinion in dressing.’ There were no changes in the relationship for 20% respondents. According to one respondent, “the same relationship of father and daughter is continuing as before”. The other changes reported included giving more responsibility to children, physical distancing from daughter, strained relationship with child, emotional distancing of the child and change in the power equation. Table 5illustrates the various adjustments made by respondents for their adolescent children. A qualitative analysis of the data revealed 50% respondents had made physical adjustments. This included providing more privacy to the children by giving a room of their own. For example, one person said, “ by this time, we came to the quarters. My son was in 9th standard and we had to give him a room. My son used to sleep in the hall before that.” Another person said, “they were given separate rooms. They did not want us to come into their rooms. We got them what they wanted for the room.” Yet another respondent said, “we looked out for houses in which there were different rooms. Before the girls and the boy were in the same room.” According to one respondent, “gave them private rooms, they wanted privacy while changing the dress so we had to do that for them.” One third (30%) respondents made emotional adjustment. This included being careful as to what was said to children and adjusting to mood swings. One respondent said, “We are careful in what we say and what we do. They are growing up now.” Another respondent said, “ their mood functions they can be terribly aggressive at one moment and low at another. They can be very independent at one moment and tearful the next. They have mood swings and I have to understand why he had these and try not to be agitated myself.” Twenty three percent (23.33%) had not made any adjustment. For example, one person said, “He already has one room so there was not much we had to do.” Another person said, “Nothing much they are just growing up that is all.” Financial adjustment had to be made by 30% respondents. This included meeting children’s needs and giving pocket money. One respondent said, “Now that they are growing up, we have to give them some pocket money which means we need to do some budgeting in the house to include this provision.” Adjustments in disciplining were reported by 6.66% respondents. One of them said, “We have given him a long rope, we don’t jump hastily to scold him, and we try to be more lenient towards him.” The other adjustments reported were giving more importance to children and adjusting to child’s demands. Table 6 depicts the various ways in which the respondents (or spouses) helped their children deal with the emotional changes in teenage. A qualitative analysis revealed that the most common way in which the respondents helped their children deal emotional changes was by being supportive (33.33%). This included being more patient with the child, having conversations with the children and not hurting the children. The following are some examples to illustrate this further. Quotation1: “ we have been told at the Church that the children should not be hurt emotionally or physically. I try to be like that. I try not to hurt them.” Quotation 2: “ she gets annoyed, I just leave her, I don’t tell her to do any work, leave her free and be patient with her.” Quotation 3: “By talking to him a lot you can help.” As far as 23.33% respondents were concerned, there were no major changes, to be dealt with. According to one of them, “there was no emotional change.” One of the ways in which 20% respondents had helped their children was by giving advice to their children when there was any behaviour problem. For example, one person said, “ if they are disrespectful I do not allow them to be, I advice them a lot about it, as to how they should talk and behave.” Giving explanations to the actions the respondents as well as explaining to the child about his or her behaviour was another way used by 13.33% respondents. One of them said, “ my daughter is not at all like grown up, she has mood changes- gets irritable. We don’t say anything; we pacify her and explain to her as to why we scolded her or asked her to behave in a particular way.” Another respondent said, “when they show insolence I am very firm with them and wont’ allow them to act like that. At that moment they may hate you. But when they have cooled down I sit with them and tell them the reason.” Thirteen percent (13.33%) had not done much to help the children go through the emotional changes. One respondent described, “they are irritable at times because of the physical growth. I did not know why they were behaving like this, I did not pay attention I did not do anything. They overcame themselves.” Being more encouraging towards the child was the way in which one respondent helped. She said, “ I encourage her to talk, share her feelings, and encourage her to mix with people.” Table 7 shows the various ways in which the respondents (or spouses) helped their children deal with physical changes that occurred in teenage. It was found that 46.66% respondents (or spouse) had helped their daughters by preparing them for menarche. The following are some of the examples. Quotation 1: “ My wife talked to her about periods. That was her department.” Quotation 2: “ I prepared daughter for menarche, told her how to use pad etc.” Quotation 3: “ I would explain to her about monthly periods. In the beginning I was a bit shy and I asked my mother to do that.” Quotation 4: “ my wife told them what to do when they get their periods. When they have their periods they will be tired, I ask them to take rest.” Forty three percent (43.33%) had not helped their children deal with physical changes. For example, one person said, “He is too young, there is no major physical change.” Another respondent said, “ I have not done anything, they are daughters so my wife may have told them.” Yet another person said, “For son, I did not have any problem, he reads a lot. He knows about these things. He has a scientific mind.” Ten percent had explained about the physical changes. One respondent said, “ when they tell me (about the changes), I tell them it is normal and there will be more changes. I had talked to them about menarche and nicely prepared them for it.” Another respondent said, “ When she came up and asked me about the changes I had explained her all these are normal changes.” Two respondents had taught grooming hygiene to their children. One of them described, “ they are physically changing, they are boys and their change is not same as girls. They have body odor, so I introduced them to deodorant. Gave them right tools to shave, dress up presentably and go out. I gave them this sort of lessons. I taught them all this clearly”. Another one said, “ they did not know how to shave, so I taught them how to shave. They have pimples, I told them how to take care of that.” About seven percent (6.66%) respondents reported that there was help from school for the children. According to one respondent, “ the school has some programs regarding using sanitary pads, they also have lessons regarding all this.” Table 8 illustrates the various stress/difficulties respondents had faced with teenage children. A qualitative analysis of the data revealed that 50% respondents had experienced difficulties related to the behaviour of the child. The following are some examples for the same. Quotation1: “ my wife and I have arguments with our daughter which is very stressful. She just doesn’t listen to us, she has become so withdrawn she is irritable and answers back to us.” Quotation 2: “ the only difficulty we face is that he spends more time on the phone talking to his friends and this really bothers us.” Quotation 3: “ if I want him to do some work, he will flatly refuse. He does not bother what others want, arguing about what he says is always right, taking back. He is arguing with his father all the time. And I have to pacify them.” Quotation 4: “ she has become adamant, she does not listen to me.” Quotation 5: “ my son is my tension, my husband can’t talk to him, he shouts back at him.” Twenty three percent (23.33%) respondents had no difficulty. According to one of them, “ no, they don’t give me any problems; they iron, wash they do their routine things.” Another person said, “ I don’t feel much stress at all. She keeps me informed about herself and her activities and I have full faith in her”. Another 23.33% had experienced the anxiety or the worry about the child’s future. One respondent described, “ How they will grow, how they will choose their career, what will happen to them- these are the questions in our minds. All this is a big stress for us.” Another respondent explained, “ you know that you have to set your own course of life, academic wise especially, spiritually, morally they have to grow values at this time. As a small child you are teaching them, but at a different level but at this age if they don’t develop it what will happen to their future. He might shape up totally different. So I have to be on my toes always. I find this very stressful.”

The fear for child’s safety was another stress reported by 20% respondents. For example, one respondent said, “ my main stress is her safety. If she is late I am tensed until she comes back. Since she is a girl anything can happen to her.” Another person said, “ When I go to my mother’s house I will be always thinking of my daughters. I can’t leave them alone here and go, what if something happens to them?” About seventeen (16.66%) percent respondents experienced financial difficulty. One respondent explained, “Every stage you have to meet the financial requirement. Financial stress is always there. We have to educate them, buy them what they need.” Another one said, “To get her into college, expenditure is there. Financially it is a problem to maintain all this.” Catering to the child’s demands was another stress reported by 10% respondents. This included cooking for the children and not able to do what one wanted due to the attention that had to be given to the child. For example, one respondent said, “It is hard work, Sometimes we have to do whatever we don’t like to do. When they have exams we can’t see TV. They feel neglected if we are with the guests and not sitting with them. When I am bored and want to do something, second son does not allow to do anything.” Other difficulties reported were worry about child’s friendship with opposite sex, decrease interest in studies and their discontent over the lack of finances at home. Discussion Adolescence is often described as a stage in which the family has to make adaptations in structure and organization in order to handle the tasks of adolescence (Preto, 1989). One such adaptation found common among respondents of the current study was the decreased use of punitive measures in order to discipline the teenagers. This observation demonstrates that families with adolescents tend to become more flexible in the handling of adolescents and they rely less on punitive measures to discipline their children. This finding is different from that of Preto’s (1989). According to Preto (1989) many families continue to reach for solutions that used to work in earlier stage, where as in the current sample, these families seem to change its strategy by being less punitive. Bringing in changes in the parent child relationship and adopting friendly approach seems to be what majority of the respondents have opted for. This finding is consistent with the need for structural shift and renegotiations of roles and relationship (Preto, 1999). Saraswathi and Ganapathi (2002) have also opined that in nucleated urbanized families parental system becomes less authoritarian, more permissive, child centered and responsive to the children. The finding but different from Sharma and Sandhu (2006) finding Indian parents are more punitive/nonreasoning, verbally hostile, physically coercive as well as autonomy granting and indulgent toward children in the ages 12-14 years than in ages 6-8 years. The structural changes are not confined to the roles, relationships and functioning of the family. Adolescence is a period when there is an increased demand for autonomy and independence and structural shifts (Preto, 1999). The current study reflects that one of the ways in which this structural shift takes place is by defining the physical boundaries and providing privacy both for the adolescence and the parents. Defining physical boundaries indicate that parents are willing to encourage autonomy to their teenaged children. Saraswathi and Pai (1997) have also reported a shift in parenting towards facilitating autonomy in adolescents. Further analysis revealed that early adolescents (ages 11-14) were more prone towards delinquency as compared to late adolescents (ages 15-18), because when children enter adolescence other persons such as peers and romantic partners become more important than parents, and their influence on the behaviour of the adolescent is quite high when compared to their parents. Due to this reason, parenting is more crucial and vital during this phase of life (Moitra & Mukherjee 2010) The finding of the study also reveals that parental relationship also experiences various kinds of shifts ranging from stronger bond, conflicts over disciplining of adolescents and worsening to past conflicts. Kluwer and Johnson (2007) have found that parental conflicts during transition to parenthood were related to lower levels of relationship quality. Studies by Ambert (2001), Cui, Donnellan and Conger, (2007) , Jenkins et.al (2005) suggest that parents can have conflicts and arguments over child-rearing which is in turn influenced by adolescent problems. These conflicts and arguments can lessen the quality of marital relationship. Implications for counseling/therapy The current findings throw light on the fact transition to adolescence does not only involve tasks for the teenager but for the parents as well. This study has implications on parental counseling/therapy in preparing them for important tasks involved in dealing with and negotiating this period of transition. The way parents and adolescents deal with this important life cycle stage, has several ramifications. Parental skills counseling, marital conflicts over adolescent problems and restructuring roles become an important focus of intervention. Shifting of marital/spousal relationships towards better quality of parenting with good parenting and problem solving skill should also be facilitated through counseling/therapy. Parents should be helped to shift their focus back on to their relationship to promote healthier and supportive partnership. Parental- children relationship also needs a shift to accommodate the changing needs of the adolescents, flexible yet reasonable and logical parental control in disciplining. This flexibility should foster growth and independence in the adolescent at the same time help children discern their parent’s authority. Reference

Sobhana H Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatric Social Work, LGBRIMH, Tezpur Sonia P Deuri Head/Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatric Social Work, LGBRIMH, Tezpur Buli Nag Daimari Psychiatric Social Worker, Department of Psychiatric Social Work, LGBRIMH, Tezpur |

Categories

All

Social Work Learning Academy50,000 HR PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS. MHR LEARNING ACADEMYGet it on Google Play store

|

SITE MAP

SiteTRAININGJOB |

HR SERVICESOTHER SERVICESnIRATHANKA CITIZENS CONNECT |

NIRATHANKAPOSHOUR OTHER WEBSITESSubscribe |

MHR LEARNING ACADEMY

50,000 HR AND SOCIAL WORK PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed