|

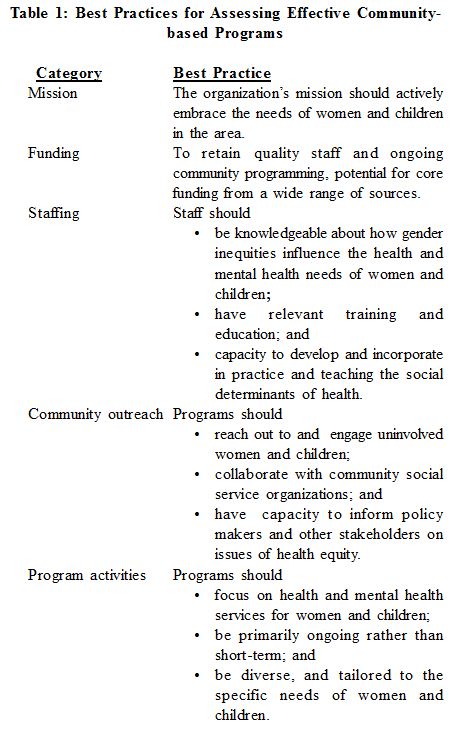

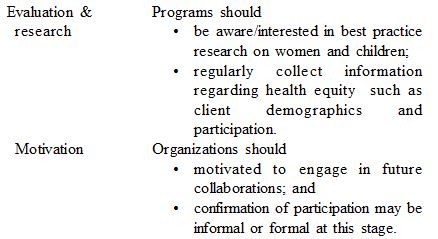

Abstract This paper describes the findings from a preliminary study conducted in five districts in Tamil Nadu, South India throughout 2009-2010. The objective was to determine the conditions necessary to conduct a health survey to examine socioeconomic factors, interrelatedness to health status and quality of life of children and mothers. Results suggest that social service organizations have the potential to improve the health status and quality of life of children and mothers in Tamil Nadu and a health survey is feasible. Implications and recommendations for conducting international preliminary studies are discussed in relation to the findings. Key words: international collaborative research, children & mothers, social work practice with communities, community development. Tamil Nadu Child and Family Health Study: A Preliminary Study The genesis for developing the Tamil Nadu Child and Family Health Study emerged from the World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Systematic differences in health within and between countries occur according to differences in socioeconomic status. Interestingly, these socioeconomics relate to lower health, regardless of the wealth of the country (Marmot, Friel, Bell, Houweling & Taylor, 2008). The authors suggest that life chances, such as high levels of illness and premature mortality, vary by birth and rearing locations. Further, the existence of such striking health inequalities is an affront to social justice and an ethical responsibility of all people to take reasonable action to avoid the inequitable distribution of power, money and resources (Marmot et al., 2008). Toward this end, the Commission on Social Determinants of Health calls for the aspiration of closing the gap in health inequity within a generation and identified three overarching recommendations that form the basis of the current study: (1) improve daily living conditions as they relate to improving the wellbeing of girls and women; (2) tackle the inequitable distribution between men and women of power, money, and resources; and (3) measure and understand the problem and assess the results of action. In order to follow these recommendations, assessments are necessary to determine feasibility and to fully understand the local conditions that lead to these inequalities. For example, Wholey (1994) explains that a lack of pre-research activities, in terms of preliminary and planning meetings can seriously hinder international collaborative research. In keeping with this recommendation and in an effort to work towards the goals set out by the World Health Organization, preparatory activities were pursued to assess the feasibility of conducting a future health survey and possible service intervention for women and children living in five districts in Tamil Nadu, India (i.e., Triuchirappalli, Thiruvarur, Thanjavur, Nagapattinam, and Ramanathapuram). The objective of this study (referred to as Phase I) was to determine the conditions necessary to conduct a health survey to examine socioeconomic factors including their interrelatedness to health status and quality of life forchildren. Specific objectives included: (a) identification of exemplary social service organizations; and (b) assessment of the receptiveness of these organizations to participate in data training and the data collection process. To accomplish the above, a multi-stage, multi-method approach was used that included a literature review to identify criteria for assessing exemplary community-based organizations, consultations with key informants, and five site visits in Tamil Nadu, South India. Literature Review Although India was one of the first of the developing countries to create a National Mental Health Program in 1982 aimed at integrating mental health care into general health care services (Srinivasa Murthy, 2003), public health statistics in India have focused mainly on mortality to the neglect of morbidity and dysfunction associated with psychiatric and psychological problems (ICMR, 2005). This neglect has resulted in the health care system being unable to provide the appropriate treatment to those in need (ICMR, 2005). Data on social and psychological determinants of health is lacking. This data would serve to augment the physical health information currently available. Specifically, population data on social and psychological determinants of health in Tamil Nadu and India are especially lacking. While not unique to India, lack of resources is amplified here, as the country is presently undergoing rapid modernization, and provisions for psychological problems are lagging behind provisions for economic development. For example, utilization of maternal health care services vary substantially among the southern states of India, with Tamil Nadu placing in the middle of the states on standard of living, education and husband’s education which are significantly associated with utilization of maternal care (Navaneetham & Dharmalingam, 2002). As a middle-income state, Tamil Nadu shows the best performance in immunization levels, lower inequalities by wealth and lower gender differentials in India (Pande & Yazbeck, 2003). Major factors contributing to infant and child mortality are vaccination and utilization of maternal health care services. Further, the utilization rates of maternal health care services also contribute to maternal mortality rates (Gupte et al., 2001). Preference toward private service provision, even in extremely low-income situations is also apparent (Navaneetham & Dharmalingam, 2002). Some have underscored the fact that the opinions and experiences of families have not been effectively assessed, which is important to understanding family involvement and mental health more clearly (Srinivasa Murthy, 1999). Here, the focus on gender disparities by the World Health Organization is brought into focus. Involving women in this type of research has become an important issue in improving quality of life for all women with attention to the changing public health and scientific research needs and opportunities in the 21st century (NIH, 1999). Certainly, attention to gender issues is essential in addressing issues of poverty, physical health and mental health (Bhogle, 1999; Kapur, 2003). Whether following natural disasters or in more stable periods, attention to gender issues are essential in addressing issues of poverty and mental health both in normal times and following natural disasters (Bhogle, 1999; Kapur, 2003). Research attention has focused on disaster relief and policy but little research has been done with respect to children and mothers unrelated to natural disasters in the general population. The role of Indian voluntary organizations is large and demonstrates a high level of concern for the needs of individuals with physical and mental health problems. In India, self-help groups, support groups, community workers and religious organizations are actively looking for effective and efficient ways of addressing these problems (Higgins, 2007). Community mental health care services have risen, primarily through the voluntary sector, responding to the need for community-based mental health care service alternatives (Srinivasa Murthy, 2003). Furthermore, the proposed study is congruent with a social determinant of health approach, which is emerging in India (Chattergee, 2009). According to Chattergee (2009), the social determinant perspective accurately reflects the multifaceted nature of the lives of the most vulnerable and recommends the training of personnel to empower grass roots community participation in developing interventions and programs and evaluating their effects. Poor health outcomes are more likely where social inequalities intersect e.g., for women and children of women with no education in poor households in rural areas (Chattergee, 2009). To assist in the selection of exemplary community-based social service organizations, the literature identifying best practices for evaluating community-based organizations was also reviewed (Carnegie Council on Adolescent Development, 1996; Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008; Delgado, 2000; Hohmann & Shear, 2002; Marmot et al., 2008; Offord & Racine, 1999; Weisman & Gottfredson, 2001; Wright, 2007). Table 1 describes and summarizes these practices. Thus, the intent of this study is to expand upon the understanding of the topic by identifying exemplary community-based social service organizations. Moreover, to determine whether exemplary community-based social service organizations adhere to these best practices, they will be applied to the study’s review of programs.

Methodology Design In an effort to address the gaps in the literature, the purpose of this preliminary study was to determine the conditions necessary to conduct a health survey, to examine socioeconomic factors interrelatedness to health status and quality of life of children and mothers. Specific objectives included: (1) identification of exemplary social service organizations; (2) explore the extent to which these organizations adhere to best practices; and (3) assess the receptiveness of these organizations to participate in data training and data collection processes. Sampling strategy and data collection A multi-stage, multi-method approach that involved key informants and site visits was employed. First, the investigative team in India identified a list of key informants from the government, academic and non-profit sectors. Second, based on the responses from the key informants, a total of five sites were identified in five districts as exemplary models based on the following criteria: (1) positive history of activities in the community, (2) collaborative activities with the community, (3) good leadership indicated by evidence of commitment to improving the lives of women and children and enthusiasm toward such efforts, and (4) infrastructure to support and maintain data training and collection and future program activities (Wright, 2007). Site visits were conducted to five sites across five districts in Tamil Nadu, South India. All of the sites were located within the districts of Triuchirappalli, Thanjavur, Thiruvarur, Nagapattinam, and Ramanathapuram. Nagapattinam, and Ramanathapuram were districts that were especially affected by the 2004 Tsunami. Throughout the site visits data were collected from key site personnel (i.e., managers, directors, medical doctors, nurses, social workers, nuns, teachers, principals, faculty, and chancellors of the participating universities) and service users through focused group discussions and consultations, review of program documents, and on-site observations to determine whether the five sites met the seven best-practice criteria outlined in Table 1. Description of the sites The site located in Triuchirappalli, site 1, was a hospital committed to serving the vulnerable populations or the underprivileged, inclusive of socioeconomic status and spiritual beliefs. Their approach to health was holistic and community oriented. The site located in Thanjavur, site 2, was a school dedicated to educating female children from the lower strata of society who would have had limited educational opportunity. In Tiruvarur, a school that evolved from providing community services for women and children to providing elementary, secondary and post-secondary education was selected as a site (site 3). Evidence of fieldwork training in social work and nursing was present at the school and was therefore familiar with assisting Masters of Social Work students in their fieldwork, research, and had infrastructure for management of students and student implemented programs and activities. The site selected from the Nagapattinam district was a community social services centre (site 4), which organized the social work programs and activities for the district. The site was involved in imparting skill training programs, awareness programs on health and hygiene, self-development programs and specialized in community development, skill training, and mental health. In Ramanathapuram, a community social services centre was selected (site 5). The aim of this organization was to provide community based social work activities, educational activities, and research. Data Analysis Members of the Canadian and Indian investigative team were present at each site visit and took detailed notes during the interviews and compared notes to ensure consensus. Data were initially reviewed in a line-by-line analysis to examine possible emerging themes within the prescribed categories derived from the literature of mission, funding, staffing, community outreach and education, program activities, capacity to evaluate and conduct research and motivation to participate in future collaborations. Using an established five-stage procedure where data are scanned, edited, refined and reassembled, themes were extracted and interpretations made within each of the categories (McCracken, 1988). Findings As previously stated, the purpose of the site visits was to determine whether the sites that were identified as “exemplary” models by the key informants met best practice criteria as discussed in Table 1. The following discusses the extent to which the sites met the best-practice criteria. Mission: All sites had clear mission statements, and their objectives and activities were well established with a focus on women and children and in the case of children, and were particularly focused on the advancement of women and girls. For example, one site had a mission statement of: “Promoting programs for preventing school dropout, to check child-labor and child abuse, and empowerment of women, especially affected by the tsunami, through education and skill training”. Funding: Two of the six data collection sites demonstrated evidence of long-term stable funding. Stable funding sources included continued local government support and support of religious organizations. Three sites had evidence of international fundraising and volunteering activities. All sites had substantial volunteer staffing support from local religious organizations and undergraduate and graduate student placements. Further, embedded within skill development programs and programs facilitated by continued student placements were microeconomic activities that supported the sites. These included training in production of arts and crafts, jewelry, organic toiletries and farming that temporarily provided employment for women and financial support for the continuation of programming. Staffing: Staff had appropriate training and post-secondary or graduate education, primarily social work and nursing degrees. The ability to maintain supportive relationships was demonstrated in relation to the continued extensive community outreach and support programs. In terms of culture, all sites expressed an inclusive care philosophy, either in mission statements or in on site interviews. Community outreach and education: The extent of ongoing programing and the extent of community outreach activities was exceptional. Each site engaged and recruited a considerable number of women, children and families both on site and off- site in the broader community. For example, sites engaged in in-patient and out-patient health services, mobile health clinics, organization of social work projects that included training and skill development programs. Program activities: Programs and services were tailored to meet specific needs of service users. Collaboration with community service providers and University programs was evident. While the majority of sites focused on skill development activities (e.g. production of jewelry, arts and crafts and sustainable farming skill), this could not be assessed at one site. As previously stated in the funding section, microeconomic activities were evident. Two sites also supported entrepreneurial business activities for participating women in order to create sustainable individualized long-term employment outside the sites. Outreach activities involving health clinics and health awareness also had staff well versed in access to community services to which participants were directed to and often provided counseling for social stressors and mental health issues. Evaluation and Research: All sites expressed an interest in participating in research activities although the extent of research and evaluation experience was unclear for the majority of sites. However, all sites reported research and evaluation activities as an integral part of training for nurses and social workers students in placement. In all of the sites visited, the infrastructure in terms of space, administrative support, and communication facilities was found to be appropriate for the purposes of gathering data for a future health study. Given the volume of programs provided, it was unclear if the programs were based on the latest research, along with evaluated targeted outcomes. Activities and participant demographics were certainly kept and were presented during on-site interviews; however, the extent to which this occurred was unclear. Motivation to participate in future collaborations: All sites were rated on a three point scale regarding motivation. The three items in the scale included: (1) lack of motivation; (2) motivated to participate in future collaborations, and (3) highly motivated to participate in future collaborations. All five sites were highly motivated to participate in future collaborations. This was evident in their agreement to sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Indian and Canadian Universities. Leaders and/or staff expressed enthusiasm to utilize skill and knowledge to serve society by participating in this study. For example, administrators of one site were enthusiastic to “utilize their expertise and knowledge to serve the society through this study”, which they think “will be an eye-opener regarding the future citizens’ and mothers’ health status”. Three sites specifically indicated the importance of making the government aware of the results to develop appropriate policies with respect to women and children. For example, the leader of one organization expressed “we hope the outcome of this study will also help the government to formulate an appropriate health policy”. Participants in focus groups also identified the importance of collecting the survey information on women and children’s health in order to formulate appropriate arguments to governing bodies to affect policies on district and state levels. One participant suggested that the United Nations should be included in dissemination of the study findings. Indeed, the desire to use data collected to advocate for local needs of women and children was identified independently by several service providers involved in separate site visits. Discussion The objectives of this study were to: (1) identification of exemplary social service organizations; (2) explore the extent to which these organizations adhere to best practices; and (3) assess the receptiveness of these organizations to participate in data training and data collection processes. After all components of the preliminary study i.e.; the literature review, key informant consultations and site visits were completed it was ascertained that there were enough resources, local interest and community investment to continue with the project. Results suggest that social service organizations in collaboration with schools of social work have the potential to improve the health status and quality of life of children and mothers in Tamil Nadu and that a health survey is feasible and warranted in order to corroborate these claims. The commitment, motivation and dedication of community partners and universities to engage in the Tamil Nadu Child and Family Study were very promising. All community partners selected were found to have appropriate infrastructure, stability of funding and a tremendous amount of community outreach activities and student involvement. Therefore, exemplary social service organizations were identified in five districts of Tamil Nadu. Although not all sites engaged in continuous formal research projects, there was a considerable amount of on-going data collection in terms of program activities and participation and substantial receptivity of participating in research activities was apparent from the site visits and evaluation. Potential learning and training opportunities exist here for faculty and students as well as community organizational members. From this evaluation it was established that this region of Tamil Nadu needed further study and that a health survey with follow-up program implementation appeared possible. Though many international studies may not have the resources to conduct site visits as a part of the initial feasibility process this particular investigation found it an important factor in assessing if the project should progress or not. The ability to provide clarification and explore project goals with potential service providers, on-site key informant consultations and the opportunity to meet staff at each site were important aspects of determining whether the project may proceed. Results from the study suggest that social service organizations in collaboration with schools of social work have the potential to improve the health status and quality of life of women and children in Tamil Nadu and a health survey is feasible. Implications for international social work practice and future research Each of the programs explored by the study set high standards for programs and services seeking to work with vulnerable communities to reach their potential. Each holds possibilities for future research and social work programming. Most simply, understanding other programs along with their successes and challenges provides a backdrop to review other social work practices. While demographics may differ, principles of empowerment and the attainment of universal human rights remain the same across cultural divides, and are especially salient for social work. Similarly, while individuals themselves may exist in different spheres, poverty and lack of access to resources is of international concern, regardless of its origin. Further, understanding linkages between social work and other disciplines, including public health and psychology can only strengthen social work practice. As globalization increases, and immigration continues to be a global trend, understanding concepts of health and mental health for the Indian community will be helpful for practitioners around the globe. Specifically, understanding some of the challenges Indians may face, and some of the potential solutions the Indian community has put into place can help to strengthen social work practice with clients of Indian origin. Similarly, as a region of the world affected by natural disaster in the recent past, lessons can be learned by other community programs facing similar challenges, with populations facing similar fears or even similar health responses to natural disaster. Social work practice may look very different in different contexts, what is termed social work in North America, may be a voluntary service, or a national program in different national settings. As this study reviewed a variety of community based program settings, the wider definition of social work practice is highlighted. This can serve to strengthen practitioners’ understanding of their roles and the multi-faceted work that they do each day. Lastly, communication across difference is a central tenant in all social work practice, as practitioners seek to work with a wide variety of communities, often different than their own. Social Work in Cross Cultural Contexts Multiple connections were made during this study, between schools and agencies, between different universities and between countries and cultures. Connections between students and agencies are common within social work education internationally, through field placements, volunteer opportunities or class field trips. In exposing students not only to programming, but the research that can inform programs, this project allowed students a greater understanding of the processes behind the creation of successful social work programming. Extensive research exists on the importance of service learning, and of the essential nature of community involvement for social work students (Hendricks et. al., 2005, Knee, 2002; Nadel, et al., 2007). This report highlights future potential for social work students to communicate across cultural contexts, presenting interesting opportunities for social work education, either virtually, or literally. Despite team members coming from two different countries (i.e. India and Canada) the commonalities that facilitated the project and enhanced the success of the project appeared to reside in the professional and academic backgrounds in social work. Specifically, these commonalities included: a common language, ethical principles, common understanding of vulnerable populations, importance of research to influence policy and particularly the commitment to social justice issues and oppression of women and children. The team members demonstrated the ability to build such sustainable and equitable partnerships which provides a template to engage students, community partners and researchers in the process of research to build lasting relationships pivotal to the success of the project. Further, the rapport built in the preliminary phase enhanced opportunities for further collaborations including the continuation of the current project and future student and faculty exchanges. Future Social Work Research The collaborative nature of this project is especially salient. Both social work practitioners and social work academics find themselves in interdisciplinary settings. Here, both Canadian and Indian researchers brought specific expertise, and were willing to give different insights into the sites visited and to the project itself. While both shared groundings in Social Work, differing experiences and contexts allowed for a diversity of opinions and ideas. The successful management of these differences was essential to the thorough review of sites and to the completion of the project. Secondly, in seeking to ‘uphold the right of clients to be offered the highest quality service possible’ (CASW, 2005), social workers must understand the populations they are working with. In reviewing criteria for sites to be reviewed, diligence is paid in understanding each from a variety of viewpoints. This diversity of expression and experience is essential in social work research, in order to fully capture data. Further, this study sets the stage for the use of commonly accepted screening tools in future studies. Here, the importance of relying on previous research is highlighted in order to ensure future reliability and translation of findings. The current findings present successful community programs, which are utilized by Indian communities, and community members facing a wide variety of life challenges. Conclusion Given the diversity of culture, research practices and general knowledge bases of the team members engaged in international research and in order to develop the professional relationships needed to successfully implement international research, preparatory activities are of the utmost importance (Riessman, 2005; Wholey, 1994). Engaging in an preliminary study is especially important in international research in order to clarify the research protocol; provide cultural adaptation and understanding amongst the investigative team, and create a collaborative research team. In its thorough review of five sites in Tamil Nadu, India this project satisfied these recommendations. Together with community practitioners, university faculty, and international consultation, many of these areas are ripe for change and for the addressing of disparities in health and access to resources. These collaborations would not be complete without the communities themselves, as their members form the basis for all interventions. It is here that this project has shown the greatest success and promise. In interacting with communities on a wide variety of levels, this project not only discovered feasibility for further work, but an abundance of hope for change, and improved conditions. It is this hope that will form the basis for the next phases of this study, and for changes in the years to come. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. This work was generously supported by a grant from the Shastri Indo-Canadian Institute. The investigative team wishes to thank many of the participants in the study that contributed their voice to the advancement of this project. The information garnered from this preliminary study provided much information regarding the potential for a successful Phase II to the proposed study, international collaborations, lessons learned, the importance of feasibility studies and the information gathered to prevent future problems from occurring for the current study as well as future studies of this nature. References 1. Bhogle, S. (1999). ‘Gender roles: The construct in the Indian context’, in T.S. Saraswathi (Ed.), Culture, socialization and human development: Theory, research and applications in India, (pp. 278-300), New Delhi, India: Sage Publications Pvt. Ltd. 2. CAUT (Canadian Association of University Teachers). (2010). Academic staff working abroad: Guidelines for working overseas. Ottawa, ON: Author. Retrieved June 26, 2011 from http://www.caut.ca/uploads/AcademicStaff WorkingAbroad_Web.pdf 3. Carnegie Council on Adolescent Development. (1994). Consultation on After-school Programs. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Corporation of New York. 4. Chatterjee, M. (2009). ‘How are social determinants of health addressed in India? ‘. Retrieved June 26, 2011 from http://www.who.int/social_determinants/the commision/ interview_Chatterjee/en/index.html 5. CIDA (2011). Promote Gender Equality and Empower Women (MDG 3). Retrieved June 26, 2011 from http://www.acdi-cida.gc.ca/acdi-cida/ACDI-CIDA.nsf/eng/JUD-131841-HC7 6. CSCH (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva, World Health Organization. 7. Delgado, M. (2000). New arenas for community social work practice with urban youth: Use of the arts, humanities and sports. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. 8. Gupte, M. D., Ramachandran, V., and Mutatkar, R. K. (2001). ‘Epidemiological profile of India: Historical and contemporary perspectives’. Journal of Biosciences, 26(4 Suppl), pp. 437-464. 9. Hackett, R., Hackett, L., and Bhakta, P. (1999). ‘The prevalence and associations of psychiatric disorder in children in Kerala, south India’. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiarty, 40(5), pp. 801-807. 10. Hackett, R., Hackett, L., Bhakta, P., and Gowers, S. (2000). ‘Life events in a south Indian population and their association with psychiatric disorder in children’. International Journal of Social Pychiatry, 46(3), pp. 201-207. 11. Hendricks, C. O., Finch, J. B., & Franks, C. L. (2005). Learning to teach, teaching to learn :A guide for social work field education. Alexandria, Va.: Council on Social Work Education. 12. Higgins, H., Dey-Ghatak, P., and Davey,G. (2007). ‘Mental health nurses’ experiences of schizophrenia rehabilitation in China and India: A preliminary study’. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 16(1), pp. 22- 27. 13. Hohmann, A., and Shear, M. (2002). ‘Community-Based Intervention Research: Coping with the “Noise” of Real Life in Study Design’. The American Journal of Psychiarty, 159, pp. 201-207. 14. Indian Council of Medical Research (2005). Mental health research in India: Technical monograph on ICMR mental health studies. Retrieved October 28, 2009 from http://www.icmr.nic.in/publ/Mental%20Helth%20.pdf 15. John, L.H., Offord, D.H., & Boyle, M.H., and Rancine, Y.A. (1995). ‘Factors predicting utilization of mental health and social services by children 6 to 16 years of age: Findings from the Ontario Child Health Study’. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 65(1), pp. 76-86. 16. Kapur, R.L. (2003). ‘The story of community mental health in India’, in S. P. Agarwal (Ed.), Mental health: An Indian perspective 1946-2003, (pp. 92-100), New Delhi, India: Elsevier, a division of Reed Elsevier India Private Limited. 17. Knee, R. T. (2002). Can service learning enhance student understanding of social work research? Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 22(1-2), 213-225. doi:10.1300/J067v22n01_14 18. Marmot, M., Friel, S., Bell, R., Houweling, T., Taylor, S. (2008). ‘Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health’. Lancet, 372(9650), pp. 1661-1669. 19. McCraken, G. (1988). The long interview. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. 20. Navaneetham, K., & Dharmalingam, A. (2002). ‘Utilization of maternal health care services in southern India’. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 55(10), pp. 1849-1869. 21. Nadel, M., Majewski, V., & Sullivan-Cosetti, M. (2007). Social work and service learning :Partnerships for social justice. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. 22. National Institute of Health (1999). Agenda for Research on Women’s Health for the 21st Century. A Report of the Task Force on the NIH Women’s Health Research Agenda for the 21st Century, Volume 1. Executive Summary. NIH Publication No. 99-4385. 23. Offord, D., & Racine, Y. (2000). Best Practices for Recreation Programs for School-Aged Children. Montreal, QC: International Children’s Institute. 24. Pande, R. P., & Yazbeck, A. S. (2003). ‘What’s in a country average? Wealth, gender, and regional inequalities in immunization in India’. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 57(11), pp. 2075-2088. 25. Prince, M. Patel, V., Saxena, S., Maj, M., Maselko, J., Phillips, M., Rahman, A., (2007). ‘Global Mental Health 1, No health without mental health’. Lancet, 370, pp. 859-877. 26. Riessman, C.K. (2005). ‘Exporting ethics: A narrative about narrative research in South India’. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 9(4), pp. 473-490. 27. Rappaport, N., Alegria, M., Mulvaney-Day, N. and Boyle, B. (2008). ‘Staying at the table: Building sustainable community-research partnerships’. Journal of Community Psychology, 36(6), pp. 693-701. 28. Srinivasa Murthy, R. (1999). ‘Socialization and mental health in India’, in T.S. Saraswathi (Ed.), Culture, socialization and human development: Theory, research and applications in India, (pp. 378-397), New Delhi, India: Sage Publications Pvt. Ltd. 29. Srinivasa Murthy, R. (2003). ‘The national mental health programme: Progress and problems’, in S. P. Agarwal (Ed.), Mental health: An Indian perspective 1946-2003, (pp. 75-91), New Delhi, India: Elsevier, a division of Reed Elsevier India Private Limited. 30. Wallerstien, N.B. and Duran, B. (2006). ‘Using Community-Based Participatory Research to Address Health Disparities’. Health Promotion Practice, 7(3), pp. 312-323. 31. Weisman, S.A. & Gottfredson, D.C. (2001). ‘Attrition from After School Programs: Characteristics of Students Who Drop Out’. Prevention Science, 2(3), 201–205. 32. Wholey, J.S. (1994). ‘Assessing the feasibility and likely usefulness of evaluation’, in Wholey, J.S., Hatry, H.P. and Newcomer, K.E., (eds), Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation, (pp. 15-39), Josey-Bass, San Francisco. 33. Wright, R. (2007). ‘Youth development and community-based arts programs: A preliminary study’. Canadian Social Work, 8(1). Accessed published January 8, 2007 http://www.casw-acts.ca/library/06Wright_e.pdf 34. Wright, R. Johns, L., and Sheel, J. (2007). ‘Lessons learned from the national arts and youth demonstration project: Longitudinal study of a Canadian after-school program’. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16(1), pp. 48-58. Wright, R. Corresponding Author: Robin Wright, Ph.D., Associate Professor, School of Social Work, University of Windsor, 401 Sunset Avenue, Windsor, Ontario, Canada N9B 3P4, Tel.: (519) 253-3000 extension 3060 Fax: (519) 973-7036, E-mail: [email protected] Krygsman, A. C.C.C., M.S.W., Ph.D. student, Counselling and Psychotherapy, University of Ottawa, Faculty of Education. Ottawa, ON. Ilango, P. Ph.D., Professor and Head, School of Social Work, Bharathidasan University, Trichy, Tamil Nadu, S. India Levitz, N. Ph.D student, School of Social Work, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON. |

Categories

All

Social Work Learning Academy50,000 HR PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS. MHR LEARNING ACADEMYGet it on Google Play store

|

SITE MAP

SiteTRAININGJOB |

HR SERVICESOTHER SERVICESnIRATHANKA CITIZENS CONNECT |

NIRATHANKAPOSHOUR OTHER WEBSITESSubscribe |

MHR LEARNING ACADEMY

50,000 HR AND SOCIAL WORK PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed