|

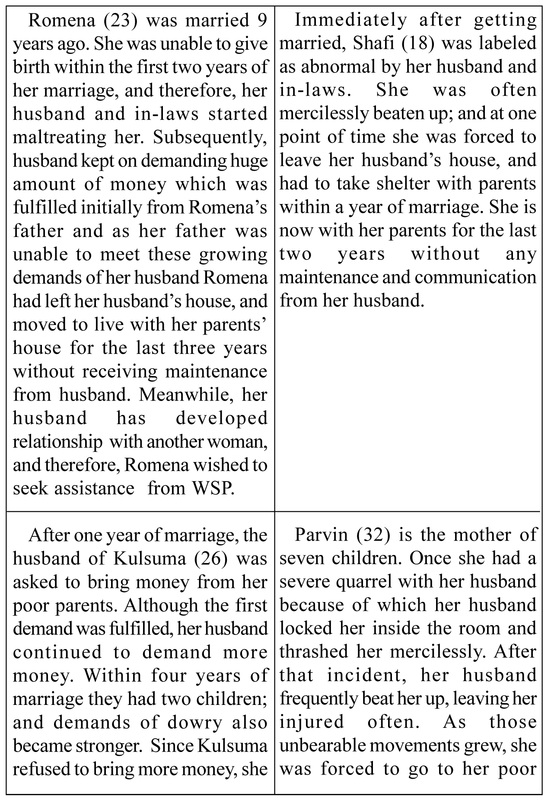

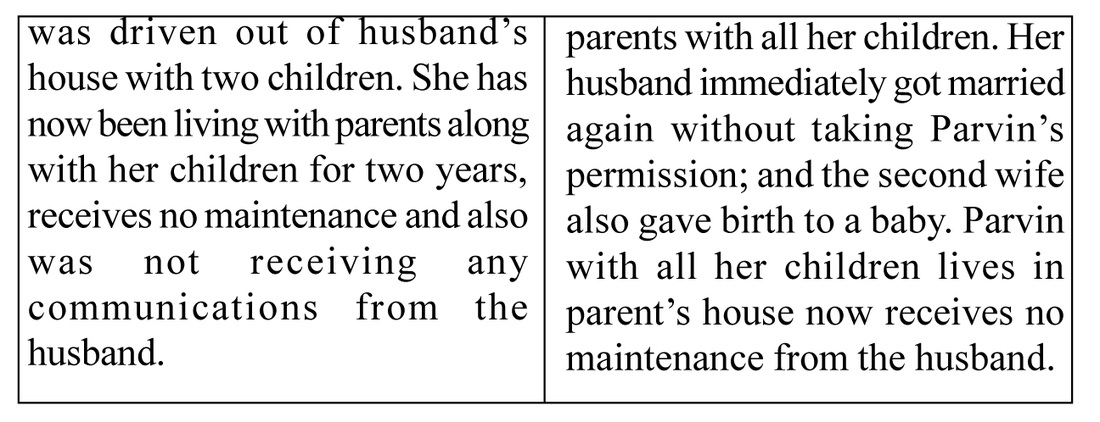

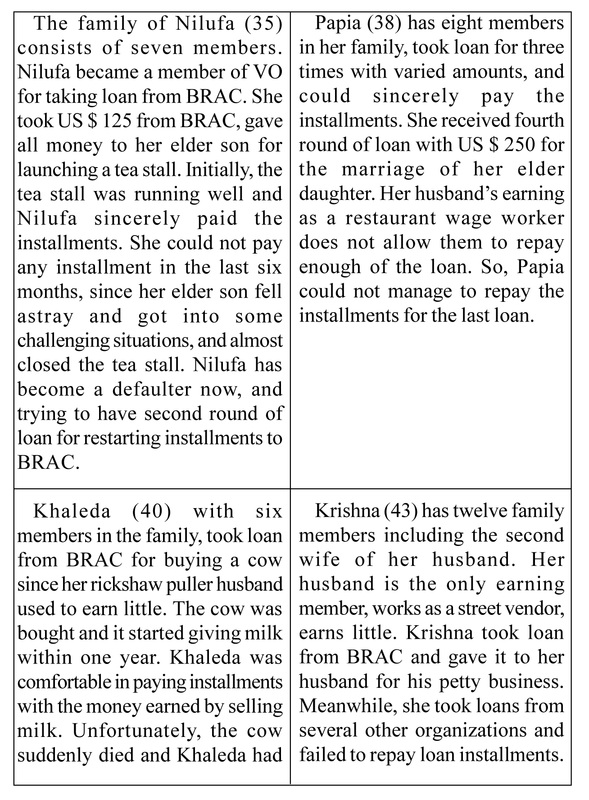

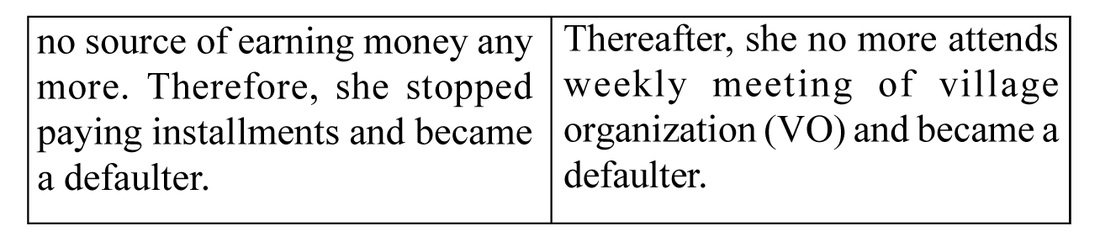

Abstract In Bangladesh, non-government organizations (NGOs) and government organizations (GOs) generally work at micro and macro levels to improve psychosocial functioning of individuals, and also for the improvement of socio-economic conditions of people. They deal with the issues of domestic violence, child rights violation, crime and delinquency, health care, poverty alleviation etc. at individual and family level. Although social work graduates are mostly found involved in these activities under NGOs and GOs, they are still not in a position to apply their academic knowledge because of lack of policy guidelines that explicitly use of social work skills within the organizations. The present study selected ‘Women Support Program’ (WSP) that deals with domestic violence and micro-credit program of Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) which addresses socioeconomic constraints of the poor women. The study explores the possibility of applying micro social work knowledge and skills in the activities of WSP and micro-credit program of BRAC by analyzing eight cases (four from WSP and four from BRAC), interviewing with the concerned workers and analyzing records kept in the office. The findings of the study identifies a certain level of limitations in the activities that are traditionally carried on by both the programs, and suggest to the efficacy of micro social work knowledge and skills for better social work outcomes. Key words: Social work practice, Bangladesh, Micro social work skills Social work practice in Bangladesh Social work education was introduced in Bangladesh in mid 1950s (Rahman, 2001; Das, 2012; Samad, 2013). Efforts were made to apply social work knowledge and skills on a modest scale to benefit the people at the field level. The practice of social work is generally perceived non-existent in Bangladesh as it appears limited in practice settings. Pertinently questions are raised around the utility of social work education in Bangladesh and at the diversity of employment in which social work graduates are being represented. The five public universities produce social work graduates that are mostly employed in different GOs and NGOs undertaking and implementing socioeconomic and psychosocial activities (Das, 2013). Some of the graduates work in public and private banking, colleges and universities, civil services and business organizations etc. (Das, 2013). Social work graduates employed in NGOs, work as development workers, and involved in planning, development and implementation of multiple socioeconomic activities (Davis, 2001; Das, 2012; Reza & Ahmmed, 2009). A portion of the graduates found employed in NGOs, also provides psychosocial guidance and counseling, advocacy, motivation to young people. Social work graduates employed in GOs and NGOs perform a wide range of activities which are very much similar and consistent with the activities of professional social workers (Das, 2012). It is to be noted that there are many workers who may not have received formal qualifications in social work but are employed and also designated as social or welfare workers in GOs and NGOs, and undertaking similar activities along with their colleagues who may have formal qualifications. The list of activities that social workers are involved is a myriad. Activities such as group formation, leadership development, group dynamics, conflict resolution, program planning and implementation, self help, self employment and employment generation, rehabilitation, resource mobilization and utilization, awareness campaign, people’s participation, women empowerment, community education, disaster management, rural development, guidance and counseling, therapy, motivation, providing legal aid and training, hospital services, correctional services, providing social security benefits etc. are undertaken in NGOs and GOs (Rahman, 2001; Das, 2012). Where social work graduates are involved in the above activities the outcomes seem to be significantly superior as a result of their rigorous training. Social work background is under represented in the Chief Executive and higher management cadres in NGOs and GOs, thus posing a significant barrier to genuine development of social work profession, and to full realization of social work outcomes for the clients. The prevailing notion amongst the social workers is that their knowledge and skills are not made full use of in the plans and strategies of the agencies in which they work. Overall in the Bangladeshi society, there is little evidence that social work is preferred profession and its scope is understood in the context of its commitment to the underprivileged (Das, 2013). Planners, policy makers, administrators are also unaware about social work education and practice, resulting in ignoring social work practice at GO and NGO levels. There seems to be enough scope for social work practice in socioeconomic development fields and psychosocial activities designed and implemented by different organizations (Rahman, 2001). But, in reality, due to lack of awareness and lack of comprehension by concerned policy makers, social work practice remains at bay in the context of Bangladesh. It is in this context the authors undertook a study to explore the activities of two selected organizations for understanding the possibility of applying social work knowledge and skills at individual and family level. The study sought to discover the effectiveness and potentials of micro social work practice (MSWP) in the context of the organization. Methodology Women Support Program (WSP) is a government organization, deals with the problems of destitute and tortured married women, and on the other hand, BRAC is an NGO, develops, plans and implements multifarious activities for socioeconomic development of the poor. Micro-credit program of BRAC is most prominent one which has been introduced to benefit the poor women living in rural and urban areas. The present study has therefore only concentrated on the activities of WSP and micro-credit program of BRAC which are purposively selected to explore the potentials of MSWP in the context of Bangladesh. The activities of WSP have been keenly observed as the researchers made several efforts to interact with its two important officials, assistant director and social welfare officer, directly involved in its core activities. Moreover, four women residing in the shelter center of WSP have been selected for conducting case study. In BRAC, two program organizers (POs) working in two different areas, directly involved in field level micro-credit activities, have been selected for interviewing. Furthermore, four women that were beneficiaries of micro-credit from BRAC have also been selected for conducting this case study. Activities of WSP WSP, although it is a program, has initially been introduced as an organization in Dhaka in July, 1995; and at present it has been operating its activities in six divisional cities namely Dhaka, Chittagong, Rajshahi, Khulna, Sylhet and Barishal of Bangladesh (Rahman, 2005; Hasan, 2011; Das, 2011; Chakraborty, 2011). The major activities of this organization are to provide legal aid, shelter, and rehabilitation to the oppressed, helpless and distressed women (Rahman, 2011; Chakraborty, 2011). It also tries to prevent and mitigate domestic violence and marital conflicts through providing counseling, mediation, arbitration, negotiation and litigation. WSP has four core components. They are (i) Cell for the prevention of violence against women (CPVAW), (ii) Women support center (WSC), (iii) ANGANA (Income generating program) and (iv) Employment information center (EIC) (Das, 2011; Rahman, 2011). All theses four components have been introduced by Dhaka divisional office of WSP. The entire four components have not been yet introduced in other divisions. WSP in Sylhet: WSP has been working in Sylhet division since October 1996, which is situated at Majumdari, close to the city hub (Chakraborty, 2011). It has undertaken multiple activities to benefit the oppressed and depressed married women of Sylhet region and these are: • Providing legal advice to the oppressed married women of all categories; • Receiving allegations of different types from oppressed married women, arranging hearing and mediation meeting between two parties, reestablishing family ties through counseling, motivation, negotiation, exchange of ideas and mutual understanding; • Filing unsettled cases of the oppressed married women in the ‘magistrate family court’ through the lawyer of the ‘legal aid cell’; • Collecting dower money and subsistence allowance from husband of the divorced and separated women with or without children; • Gathering information and following up legal actions with regard to women oppression due to dowry demands, illegal divorce or separation, illegal second marriage, non-recognition of wife, refusal of fatherhood of the child, and in case of denying maintenance; and • Collecting information about different types of criminal offences like rape, kidnapping, murder for dowry, trafficking, acid throwing etc. and taking actions accordingly (Rahman, 2005; Chakraborty, 2011; Das, 2011; Rahman, 2011; Hasan, 2011) in addition the agency WSC has introduced, provision of possible security and temporary shelter (not more than six months) to the shelter-less women with children aged below 12 years of age. In these shelters they are provided with food; training; clothes; social work treatment; counseling and primary education free of cost. WSC in Sylhet has introduced sewing for the women residing in the shelter; (ii) Providing medical treatment for ensuring physical and mental health of the recipient women and making them self reliant with all types of support including legal aid; and (iii) Taking steps toward improving the quality of life and modifying the behavior pattern of the recipients and child inmates staying in the ‘shelter center’. Nature of cases dealt with by WSP: WSP handles multiple types of ‘cases’. A ‘case’ may have any of the following or a combination of the causes such as a woman with mostly marital problems that cause disaster to her life. Women suppressed because of dowry demands; illegal second marriage of the husband; husband having illicit relationships; drug addiction of the husband; torture committed by husband and in-laws; forced separation; arbitrary divorce; not recognizing non-registered and secret marriage; denying maintenance; not accepting the fatherhood of the child; misunderstandings and conflicts in conjugal life etc. The study has conducted four case studies which have been explained below. Activities of BRAC Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) is today the largest international non government organization which has been working in eleven countries across the world including Bangladesh. The organization started its activities as a relief organization in the name of Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance Committee (BRAC) in 1972, aiming at serving the refugees returning to Bangladesh from India after the liberation war in 1971 (Chowdhury & Bhuiya, 2004; BRAC, 2004; Develtere & Huybrechts, 2005; Reza & Ahmmed, 2009; BRAC, 2012). Later on, it turned its focus on poverty alleviation, empowerment of the poor, especially women empowerment, mostly in the rural areas of Bangladesh. The organization was subsequently renamed as Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC), which has become simply BRAC since 1996 (Chowdhury & Bhuiya, 2004; BRAC, 2012). It is reported that around 126 million people in the world have been benefited one way or the other due to the activities performed by BRAC (BRAC, 2012). BRAC has right now introduced multidimensional programs like agriculture and food security, community empowerment, disaster, environment and climate change, education, gender justice and diversity, health, nutrition and population, human rights and legal aid services, integrated development, microfinance, services to the potential migrants (migration), targeting the ultra poor, water, sanitation and hygiene, enterprise and investments throughout the country (Halder, 2003; Develtere & Huybrechts, 2005; Reza & Ahmmed, 2009; BRAC, 2013). Among all the programs introduced by BRAC, only micro-credit program has been purposively chosen for this study for understanding its entire activities that have been supposedly benefiting the poor. There are a number of NGOs operating micro-credit program in Bangladesh (Das & Kazal, 2007; Reza & Ahmmed, 2009). BRAC, as an NGO, commenced its micro-credit program in 1974. Currently the target populations for micro-credit program of BRAC are rural and urban poor women, youth and adolescents, migrant workers and small entrepreneurs (BRAC, 2012). Micro-credit program was first implemented in the vast rural areas of Bangladesh. Only in 1997, BRAC introduced micro-credit program in the urban areas to address urban poverty (BRAC, 2004). After the commencement of micro-credit program, BRAC has so far disbursed US $ 8.6 billion among 5.2 million borrowers; and the repayment rate of the borrowers has been reported as excellent (BRAC, 2012). The borrowers who are mostly women use the loans to manage their household finances and engage themselves in diverse income generating activities. The women get united among themselves under village organization (VO) which brings gender solidarity, resulting in challenging the age-old patriarchal dominance at the family and community level (Parmar, 2003; Chowdhury & Bhuiya, 2004). BRAC works for socioeconomic empowerment for the poor and destitute women under micro-credit program. It provides collateral free credit to its borrowers, and it ensures that the borrowers regularly save a certain amount of money. It also takes initiative to form a group that consists of around 30 to 40 women from the local community; the group is generally termed as VO, also considered vital organ for administering basic activities (Rafi & Mallick, 2002; BRAC, 2004; Chowdhury & Bhuiya, 2004; Reza & Ahmmed, 2009; BRAC, 2012; BRAC, 2013). The VO plays very vital role to bring the member women to one platform where they can interact with each other, can have access to finance and information, share information and raise awareness among themselves regarding contemporary issues that affect their daily lives (Parmar, 2003; Reza & Ahmmed, 2009; BRAC, 2012). VO of BRAC in the local community serves as an informal guarantor as it creates peer pressure on member borrowers for timely repayment of the loan. The borrowers are expected to repay the weekly installment regularly; and they deposit savings during the weekly meeting of VO (Alam, 2003; Develtere & Huybrechts, 2005; Reza & Ahmmed, 2009). The loans taken by women are generally invested in poultry farm, livestock rearing, fruit and vegetable cultivation, handicrafts or rural trade which create self employment (BRAC, 2012). Nature of cases dealt with by BRAC: Micro level and direct social work practice

Social work practice is undertaken at micro, mezzo and macro levels. Micro level social work practice refers to practicing social work directly with individuals, small groups, and families (Turner, 2005; Kirst-Ashman, 2010). Zastrow (2010) classifies social work practice into three levels- (a) micro- working with individuals on one-to-one basis; (b) mezzo- working with families and other small groups; and (c) macro- working with organizations and communities. We see MSWP as direct social work practice. Practicing social work directly with individuals and families has also been termed as direct practice (Turner, 2005; Ambrosino, Ambrosino, Heffernan & Shuttlesworth, 2008). On the other hand, working with individuals, couples, families, and groups is again considered as direct practice (Midgley, 2001; Hepworth, Rooney, Rooney, Strom-Gottfried & Larsen, 2010). Social workers are at present mostly found engaged with direct practice, accepting and working with individual clients, their family members and trying to resolve the problems of clients. In the current study, working with individuals and family has been described as MSWP. But the categorization of different level of social work practice often becomes blurred since social work with individuals remains incomplete without dealing with family members and in many cases with the community people in which an individual lives. It is perceived that the activities undertaken by WSP and BRAC are close to the activities that are generally adopted by micro social work practitioners. The present study focuses on social work practice with individuals, families and individuals in groups who are also the target population of WSP and BRAC. Although the success of both the organizations has been claimed as considerable, practicing micro social work with the service seekers and effectively working with their family constellations would bring about much better results than current outcomes. It is also felt that due to lack of social work knowledge, the workers of the organizations, in many cases, cannot effectively deal with the problems of the service seekers, resulting in partial success, even in some cases ending in a failure. Knowledge and skills like individual problem solving, family therapy, dissemination of information, guidance and counseling, motivation, assessment of the situation, mediation, negotiation, advocacy, networking, referral, follow up etc. related to MSWP have been tested for understanding the effectiveness in the activities undertaken by WSP and BRAC. In the current study, an effort has been made to examine and evaluate the potentials of different pieces of social work knowledge and skills related to MSWP in order to perceive their effectiveness in dealing with the service seekers coming to seek help from WSP and BRAC. The authors also could find evidence of micro social work perspectives like strengths-based practices, evidence based and ecosystem perspectives for their effectiveness in the activities of WSP and BRAC. Theories followed in MSWP like role theory, cognitive theory and person-centred theory etc. have also been examined for understanding their potentials in the activities of WSP and BRAC if applied. The processes of micro practice Women come to WSP with allegations of physical and psychological torture committed mostly by husband and in-laws. WSP records these allegations and asks the complainants and the husband and/or in-laws to be present before the workers on a given date. WSP listens to both the parties and tries to mediate between them. The workers sit with both the parties as many times as necessary to mediate and diffuse tensions and bring about compromise. Sometimes, authorities call the chairman/members of local government from respective regions and try to resolve the problems with their active help and cooperation (Rahman, 2005; Chakraborty, 2011; Das, 2011). When such efforts do not resolve the problems the organization files a formal case in the court against the defendant (Rahman, 2011; Hasan, 2011). During the hearing of the case all expenses such as court fees and the lawyers’ fees are borne by the WSP authorities. If the problem is resolved through mediation and arbitration on some specific conditions, then the authorities follow it up to ensure the conditions to be fulfilled. The women who are traumatized because of physical and/or mental torture by the husband or in-laws, the WSP authorities provide counseling, sympathy, motivation etc. to assist them healing and to release their agony (Rahman, 2011; Chakraborty, 2011; Hasan, 2011). The women who do not have a shelter and cannot go to family home with the husband are generally taken to ‘shelter center’ of WSP (Chakraborty, 2011; Rahman, 2011; Das, 2011). In most cases, WSP workers are found not sufficiently skilled to make proper assessment of the situation of the complainant and this may be due to their lack of training or preoccupation with crisis and legal work (Rahman, 2005; Chakraborty, 2011; Das, 2011). When mediations between the two parties are planned and held, WSP authorities are often unable to explain the rights and privileges of the victims before the defendants, resulting in uncompromising attitude shown by the husbands and his relatives. This once again is a lacuna in the training and understanding of social work values in the WSP workers. Since the workers and managers do not have a full understanding of mediation and arbitration processes a very mediocre level of mediation is seen and the victim often feels neglected and not validated. Although the workers of WSP take up the motivation strategy to gear up the depressed women, they frequently remain unsuccessful to motivate the complainants for helping them overcome the barriers and starting afresh. The way counseling is provided to the husband, in-laws even sometimes to the wife does not seem to be very effective as the person playing the role of a counselor do not have training on it (Rahman, 2011; Chakraborty, 2011; Hasan, 2011). WSP workers appear to be lacking in skills to deal with their advocacy roles. Thus the service recipients receive very little by way of advocacy from the workers. It is observed that the WSP workers only target to resolve the problems by any means without understanding and assessing the entire situation causing less viable solutions to the problems. Due to the complicated legal and economic framework that most WSP workers take there is a general failure of social work function especially in micro practice contexts in this situation. Previous studies corroborate that because of lack of effective follow up many cases remained unresolved (Rahman, 2005; Chakraborty, 2011; Hasan, 2011) In the micro-credit program of BRAC, program organizers (POs) visit the VO once a week and receive weekly installments from the borrowers. They inspire the members to take pledge for the commitment of complying with the rules and regulations of BRAC, make them aware of social issues and help resolve conflicts among the members (Rafi & Mallick, 2002). Sometimes POs put pressure, take coercive actions or influence the group members to pressurize the defaulters for ensuring weekly installments (Parmar, 2003; Develtere & Huybrechts, 2005). The borrowers hardly get any chance to invest the loan in any productive economic activity since weekly installment has to be made immediately. The loan is of small amount and is therefore invested in rudimentary types of economic activities (Alam, 2003; Ahmad, 2007; Das, 2012). POs do not counsel, neither do they motivate the defaulters for productive utilization of loans. The knowledge and skills of MSWP like counseling and guidance, motivation, advocacy, networking, utilization of resources, using inner strength, encouraging self autonomy and self determination, dissemination of information, planning and problem solving capacity, understanding individual and family etc. are not followed in micro-credit program. The context of microskills Guidance and counseling is considered important professional knowledge and skill in MSWP. The application of this knowledge and skill in a particular context may bring about success. The activities of WSP may be better performed by micro social work practitioners. Therefore, the potentials of applying guidance and counseling in the activities of WSP may be worthwhile. Likewise, micro-borrowers of BRAC with motivation, guidance and counseling may utilize the loan better. Moreover, MSWP can make the borrowers enable, empowered, motivated, self reliant, educated, self directed, confident, capable of solving problem and better planning, help proper utilization of resources etc. The problems of service seekers to WSP and BRAC may be better resolved through taking the situation of the family into consideration, and therefore, family counseling and family therapy of MSWP seem to be more applicable. Besides, application of mediation, arbitration and negotiation of MSWP in resolving the problems of women under WSP may produce better outcomes. The techniques of assessment and evaluation followed in MSWP could be useful for understanding the situation of help seekers to WSP and BRAC for better planning and solutions of the problems. Sympathy and empathy skills practiced by micro social workers can influence the clients and workers of both the organizations to establish rapport and facilitate achieving the desired goals. The WSP and BRAC workers generally do not act as catalyst, broker and advocate to negotiate with and benefit the service seekers. Moreover, coordinating and networking with potential organizations and proper utilization of resources are rarely followed by the workers of the respective organizations. Applying the knowledge and skill of coordination and networking in the activities of WSP and BRAC can bring about greater success. Strengths based and ecosystem perspectives followed in MSWP may be useful in the activities of both the organizations. Strengths based perspectives (SBPs) concentrates on the inherent strengths of individuals but do not ignore the challenges and limitations of the person (Kirst-Ashman, 2010; Zastrow, 2010). It is also based on building and fostering hope from within and working with precedent successes of the individual service seekers (Pulla, 2012). If the SBPs are followed, the service seekers to both the organizations could become mentally strong and confident which will, in turn, bring them lots of hopes and strengths. Ecosystem perspectives deal with the core principle ‘person-in-environment’ or “how people and their environment fits” (Miley, O’ Melia & Dubois, 2004; Payne, 2005) According to ecosystem perspectives, a person is a product of social, economic, political and natural forces; and she/he constantly interacts with all these forces in the society (Pulla, 2012). The purpose of the perspectives is to serve the individuals to eliminate or alleviate stresses by connecting with personal and environmental resources so that effective coping could be worked out (Payne, 2005; Terry, 2008; Gitterman, 2011). Some of the theories like role theory, person-centred theory and cognitive theory followed in MSWP may also be effectively used in the activities of WSP and BRAC. Role theory explains that person’s functioning is always influenced by many societal behavior expectations and person’s interactions with others. A particular role played by an individual has been shaped and reshaped through multiple societal processes (Turner, 2005; Das, 2012). A service seeker to WSP or BRAC is not an alienated case rather her role and expectations of her role by others make situation complicated, causing multifarious problems for her life. Role theory helps the social workers address potential and actual problems, risks, harm and injustices associated with client’s role functioning and role expectations (Kimberley & Osmond, 2011). Person-centred theory emphasizes client’s present experiences, reduces the authority of help providers and tries to understand how a client perceives an event which has affected him/her (Turner, 2005; Payne, 2005). Conflicts and inconveniences grow when the sense of self and the experience gained through interaction with others does not match. Applying person-centred theory may ensure genuine respect and value for the service seekers which could be empowering and may also help them innovate ways for achieving self fulfillment and self determination (Payne, 2005; Rowe, 2011). Therefore, this theory which is mostly practiced by micro social workers may also be adopted in the activities of both the organizations for achieving the desired goals. Cognitive theory followed in MSWP helps individuals identify their negative thoughts and misconceptions that may have become troublesome and encourages them to alter the old one replacing with new pattern of thinking that brings solutions (Payne, 2005; Chatterjee & Brown, 2011). It believes people are creative and flexible, capable of reshaping irrational aspects of their life to respond to others and situations (Turner, 2005). The theory has the potentials to be used in the activities of WSP and BRAC which will make the service seekers self determined, goal oriented and autonomous. Barriers towards applying micro social work Currently both WSP and BRAC do not have much presence of social work graduates. It is envisaged that future recruitments of social work graduates may be useful to generate better outcomes for the organization. Managers in both these agencies would probably gain more by following a professional approach that allows them to be client centred. Our research has also brought to surface that social work graduates due to their small number are unable to influence the policy frameworks in the organizations. The pressure on return of investment is so high that the micro-credit program of BRAC seem to be less interested in the poor and their multifarious problems rather they are more interested in ensuring the loans to be recovered (Alam, 2003; Ahmad, 2007; Das, 2012). Policy makers at state level as well as organizational level do not have enough knowledge about social work which creates obstacles toward the application of knowledge and skills of social work in their activities (Samad, 2009). More studies on the applicability of micro social work in the activities of WSP and BRAC micro-credit program are required to engage further discussion on the potentials of MSWP in the contexts of Bangladesh. Conclusion It is understood that the activities developed and implemented by WSP and BRAC may be described as potential areas where MSWP may be introduced. The activities of both the organizations are very close to the activities of social work practitioners. The current study makes a humble effort to explore the potentials of micro skills practice in the activities of agencies such as WSP and BRAC micro-credit program. It is shown that the knowledge systems and skills used in MSWP may also be used while performing the activities under WSP and BRAC. The negative effects of the activities of both the organizations perhaps could well be handled if MSWP introduced. But it is strongly felt that MSWP in this regard may bring about much better results. Further researches on potentials of MSWP in the activities of WSP and BRAC may be suggested based on the findings of this study. References 1. Ahmad, Q. K. (Ed.). (2007). Socio-economic and indebtedness-related impact of micro credit in Bangladesh. Dhaka: The University Press Limited. 2. Alam, M. F. (2003). Final report on BRAC BDP. (Unpublished field work report). Department of Social Work, Shahjalal University of Science & Technology, Sylhet. 3. Ambrosino, R., Ambrosino, R., Heffernan, J., & Shuttlesworth G. (2008). Social work and social welfare: An introduction (6th ed.). Belmont CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole. 4. BRAC. (2004). BRAC Annual Report 2003, Dhaka: Author. Retrieved from http://www.brac.net/sites/default/files/Brac%20Annual%20Report%202003.pdf 5. BRAC. (2012). BRAC Annual Report 2011, Dhaka: Author. Retrieved from http://www.brac.net/sites/default/files/BRAC-annual-report-2011.pdf 6. BRAC. (2013). BRAC Annual Report 2012, Dhaka: Author. Retrieved from http://www.brac.net/sites/default/files/BRAC-Annual-Report-2012.pdf 7. Chakraborty, J. (2011). Final report on women support program (WSP). (Unpublished field work report). Department of Social Work, Shahjalal University of Science & Technology, Sylhet. 8. Chatterjee, P., & Brown, S. (2011). Cognitive theory and social work treatment. In F. J. Turner (Ed.), Social work treatment: Interlocking theoretical approaches (5th ed., pp. 103-116). New York: Oxford University Press. 9. Chowdhury, A. M. R. & Bhuiya, A. (2004). The wider impacts of BRAC poverty alleviation programme in Bangladesh. Journal of International Development, 16, 369–386. doi: 10.1002/jid.1083 10. Das, T. K., & Kazal, M. M. H. (2007). The policy of ‘job for all and education for all’ and the empowerment of the poor in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Public Administration, 16(1), 111-123. 11. Das, T. K. (2012). Applicability and relevance of social work knowledge and skills in the context of Bangladesh. SUST Studies, 15(1), 45-52. 12. Das, T. K. (2013). Internationalization of social work education in Bangladesh. In T. Akimoto & K. Matsuo (Eds.), Internationalization of Social Work Education in Asia. Tokyo: ACWelS and APASWE. 13. Das, U. C. (2011). Final report on women support program (WSP). (Unpublished field work report). Department of Social Work, Shahjalal University of Science & Technology, Sylhet. 14. Davis, P. R. (2001). Rethinking the welfare regime approach: The case of Bangladesh. Global Social Policy, 1(1), 79-107. doi: 10.1177/146801810100100105 15. Develtere, P., & Huybrechts, A. (2005). The Impact of Microcredit on the Poor in Bangladesh Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 30, 165–189. doi: 10.1177/030437540503000203 16. Gitterman, A., & Germain, C. B. (2008). In T. Mizrahi & L. E. Davis (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Social Work (20th ed. Vol. 2, pp. 97-102). New York: Oxford University Press. 17. Gitterman, A. (2011). Advances in the life model of social work practice. In F. J. Turner (Ed.), Social work treatment: Interlocking theoretical approaches (5th ed., pp. 279-292). New York: Oxford University Press. 18. Halder, S. R. (2003). Poverty outreach and BRAC’s microfinance interventions: Programme impact and sustainability. IDS Bulletin, 34(4), 44-53. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2003.tb00089.x 19. Hasan, A. S. M. M. (2011). Final report on women support program (WSP). (Unpublished field work report). Department of Social Work, Shahjalal University of Science & Technology, Sylhet. 20. Hepworth, D. H., Rooney, R. H., Rooney, G. D., Strom-Gottfried, K., & Larsen, J. A. (2010). Direct social work practice: Theory and skills (8th ed.). Belmont CA: Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning. 21. Kimberley, D., & Osmond, L. (2011). Role theory and concepts applied to personal and social change in social work treatment. In F. J. Turner (Ed.), Social work treatment: Interlocking theoretical approaches (5th ed., pp. 413-427). New York: Oxford University Press. 22. Kirst-Ashman, K. K. (2010). Introduction to Social Work & Social Welfare: Critical Thinking Perspectives. Belmont CA: Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning. 23. Midgley, J. (2001). Issues in international social work: Resolving critical debates in the profession. Journal of Social Work, 1(1), 21-35. doi:10.1177/146801730100100103 24. Miley, K., O’Melia, M., & DuBois, B. (2004). Generalist social work practice. New York: Pearson. 25. Parmar, A. (2003). Micro-credit, empowerment, and agency: Reevaluating the discourse. Canadian Journal of Development Studies, 24 (3), 461-476. 26. Payne, M. (2005). Modern social work theory (3rd ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 27. Pulla, V. (2012). What are strengths based practices all about? In V. Pulla, L. Chenoweth, A. Francis & S. Bakaj (Eds.), Papers in strengths based practice (pp. 1-18). New Delhi: Allied Publishers. 28. Rafi, M., & Mallick, D. (2002). Group dynamics in development of the poor: Experience from BRAC. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 13(2), 165-178. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27927774 29. Rahman, A. (2005). Final report on women support program (WSP). (Unpublished field work report). Department of Social Work, Shahjalal University of Science & Technology, Sylhet. 30. Rahman, M. M. (2011). Final report on women support program (WSP). (Unpublished field work report). Department of Social Work, Shahjalal University of Science & Technology, Sylhet. 31. Reza, M. H., & Ahmmed, F. (2009). Structural social work and the compatibility of NGO approaches: a case analysis of Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC). International Journal of Social Welfare, 18, 173–182. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2397.2008.00604.x 32. Rowe, W. (2011). Client-centered theory: The enduring principles of a person-centered approach. In F. J. Turner (Ed.), Social work treatment: Interlocking theoretical approaches (5th ed., pp. 59-76). New York: Oxford University Press. 33. Samad, M. (2009). Development of social work education in Bangladesh and need for Asia-Pacific regional cooperation. In Proceedings, Seoul international social work conference (pp. 174-188). Seoul: Korea Association of Social Workers. 34. Samad, M. (2013). Social work education in Bangladesh: Internationalization and challenges. In T. Akimoto & K. Matsuo (Eds.), Internationalization of social work education in Asia. Tokyo: ACWelS and APASWE. 35. Turner, F. J. (2005). Micro practice. In F. J. Turner (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Canadian social work (pp. 236-237). 36. Turner, F. J. (2005). Role Theory. In F. J. Turner (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Canadian social work (pp. 325-326). Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. 37. Turner, F. J. (2005). Person-centred theory. In F. J. Turner (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Canadian social work (pp. 276-277). 38. Turner, F. J. (2005). Cognitive theory. In F. J. Turner (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Canadian social work (p. 73). 39. Zastrow, C. (2010). Introduction to social work and social welfare (10th ed.). Belmont CA: Brooks/Cole. Tulshi Kumar Das Professor, Department of Social Work, Shahjalal University of Science & Technology, Sylhet, Bangladesh, Md. Fakhrul Alam Assistant Professor, Department of Social Work, Shahjalal University of Science & Technology, Sylhet, Bangladesh. |

Categories

All

Social Work Learning Academy50,000 HR PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS. MHR LEARNING ACADEMYGet it on Google Play store

|

SITE MAP

SiteTRAININGJOB |

HR SERVICESOTHER SERVICESnIRATHANKA CITIZENS CONNECT |

NIRATHANKAPOSHOUR OTHER WEBSITESSubscribe |

MHR LEARNING ACADEMY

50,000 HR AND SOCIAL WORK PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed