|

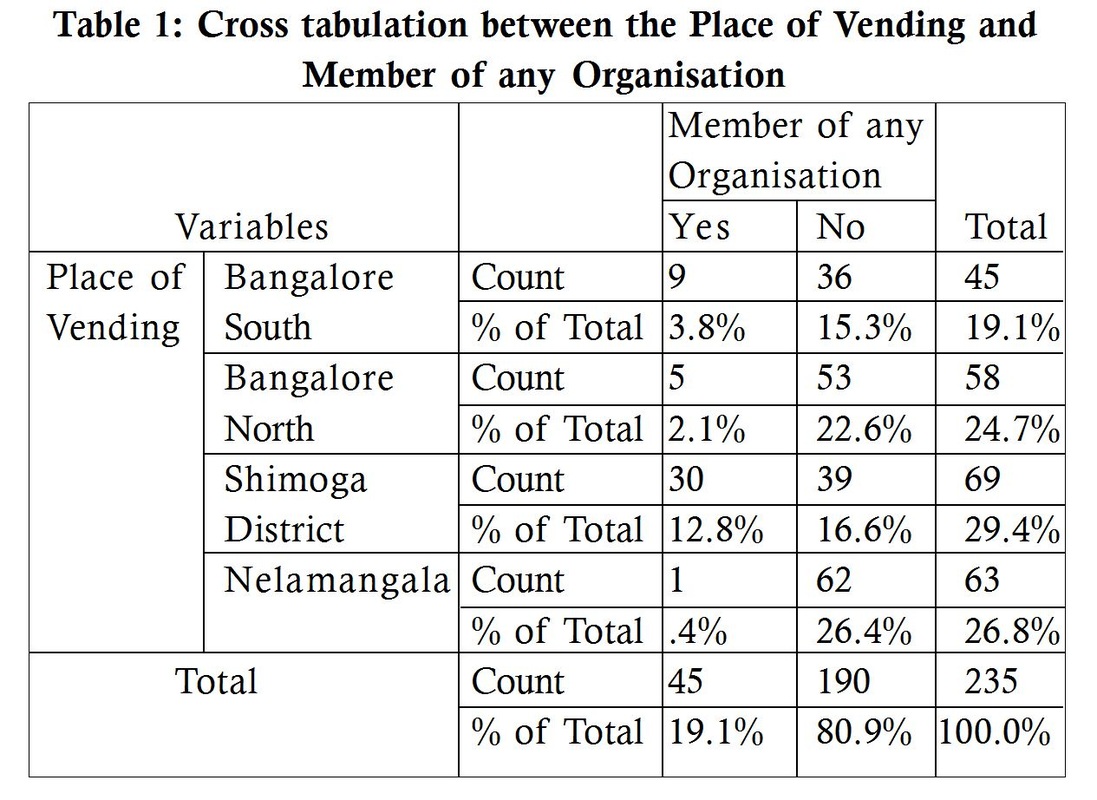

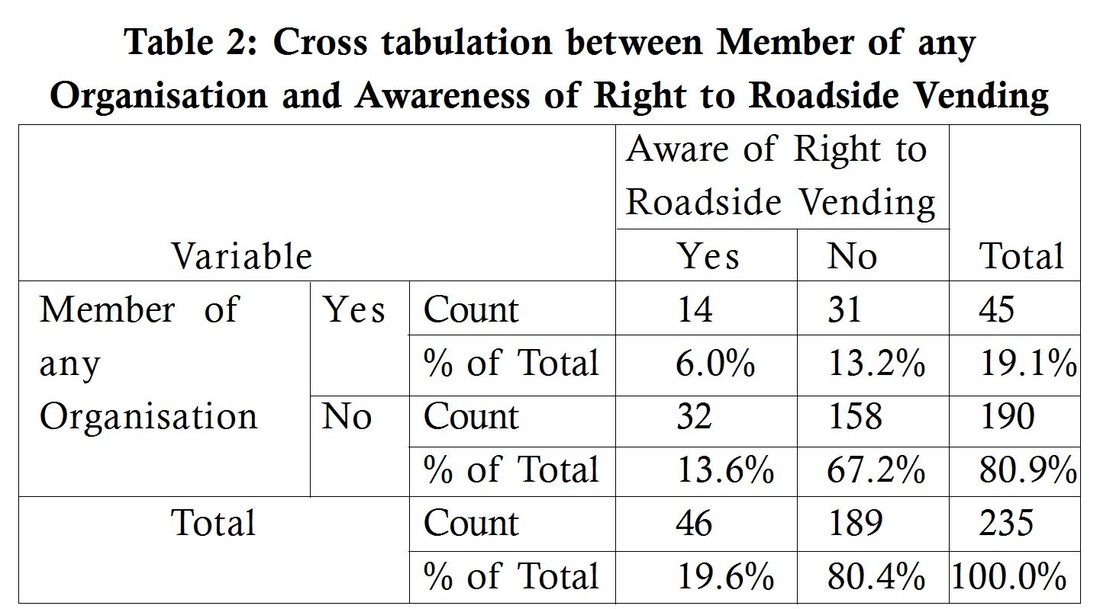

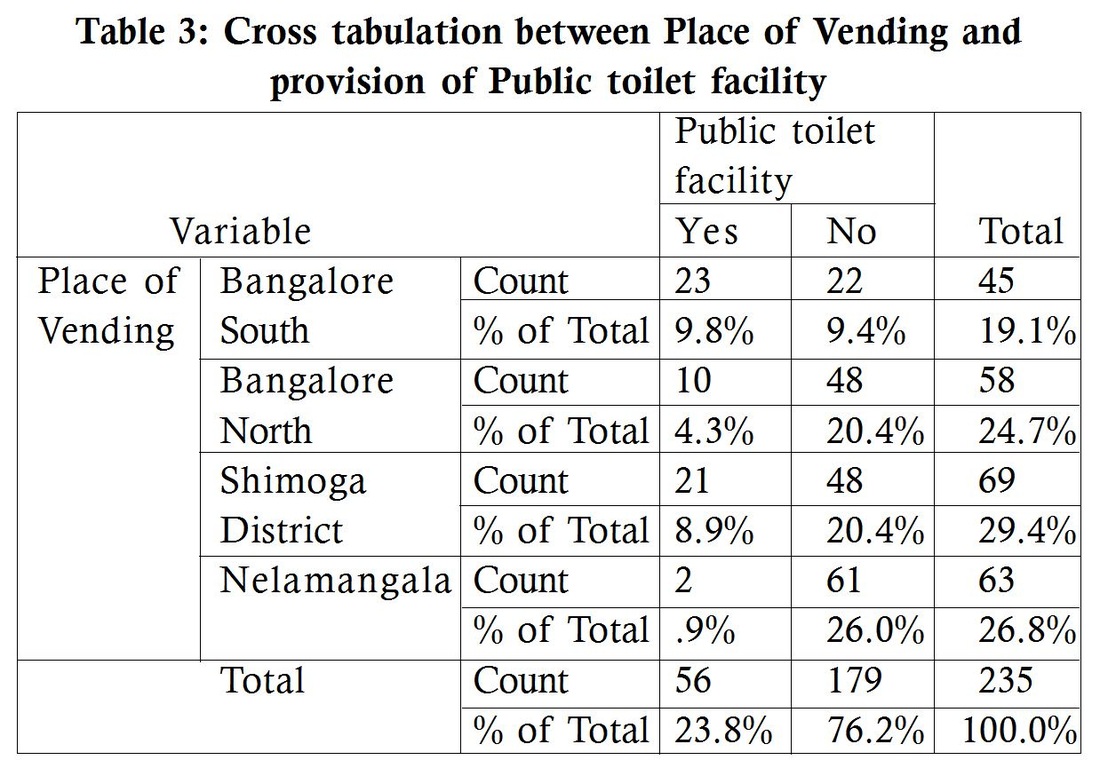

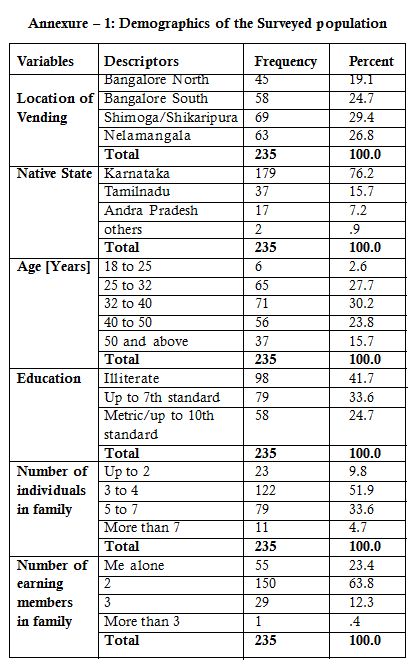

Abstract Ever growing urban amalgamations attract people from other geographical regions as an attractive employment destination. Most of these migrants lack skill or education or both in securing a job in formal / organized sector. Also, in densely populated cities, many inmates face the problem of unemployment due to various reasons. Some of these reasons encourage men and women to take up vending on streets. Historically, street vending has been a part of our culture and tradition. During the time of Krishna Deva Raya, in Vijayanagar Empire, street vending included selling of gold and silver articles. In the recent times, street vending includes selling of eatables, vegetables and fruits, toys, cloth, woolen carpets and even electronic goods. Street vendors form an integral part of our socio – cultural and economic life. Reports indicate that,street vendors constitute approximately 2 per cent of the population of a metropolis and they contribute significantly to economy. But, it is difficult to get a precise measure of population of street vendors and their contribution to economy. In the present paper, the results of data gathered through interaction with more than 100 women street vendors across various localities of Bangalore is presented to identify some of the Issues and concerns of women street vendors. A high percentage of women in the age group of 25 to 40 years with low education level working for more than 8 hours a day have explained their plights during the study. These women bear the brunt of what is termed as ‘illegal and arbitrary eviction of street vendors’ as a very high percentage of women depend on their earnings. 1. Introduction: Street Vending has been an integral part of the tradition and culture of India, ever since the civilization in India grew up to the nascent trading. Hence, Street vending in India is as old as the trade itself. In the past, given very less pressure of population on the geographies, Street Vending was either considered part of normal trade or was accepted as one of the ways of trading. In the early 1900’s with the beginning of the monetization of land coupled with increasing pressure of population on the geographies; out of necessity, vendors spilled over to streets and found many people watching them and waiting for them to sell their articles. In the recent past, particularly in the last 40 years, Street Vendorsare being noticed as aberrations on the Streets particularly with monetization of land at its unprecedented peak and excessive pressures of population on the geographies. Now, these people – Street Vendors – form a formidable population, variously called but generally grouped as belonging to Informal Sector of the Economy. 2. Historical and recent debates on informal economy: Street vendors in Mexico City; push-cart vendors in New York city; rickshaw pullers in Calcutta; jitney drivers in Manila; garbage collectors in Bogotá; and roadside barbers in Durban. Those who work on the streets or in the open air are visible informal workers. Other informal workers are engaged in small shops and workshops that repair bicycles and motorcycles; recycle scrap metal; make furniture and metal parts; tan leather and stitch shoes; weave, dye, and print cloth; polish diamonds and other gems; make and embroider garments; sort and sell cloth, paper, and metal waste; and more. The least visible informal workers, the majority of them women, work from their homes. Home-based workers are to be found around the world. They include: garment workers in Toronto; embroiderers on the island of Madeira; shoemakers in Madrid; and assemblers of electronic parts in Leeds. Other categories of work that tend to be informal in both developed and developing countries include: casual workers in restaurants and hotels; subcontracted janitors and security guards; day labourers in construction and agriculture; piece-rate workers in sweatshops; and temporary office helpers or off-site data processors. Conditions of work and the level of earnings differ markedly among those who scavenge on the streets for rags and paper, those who produce garments on a subcontract from their homes, those who sell goods on the streets, and those who work as temporary data processors. Even within countries, the informal economy is highly segmented by sector of the economy, place of work, and status of employment and, within these segments, by social group and gender. But those who work informally have one thing in common: they lack legal and social protection. Over the years, the debate on the large and heterogeneous informal economy has crystallized into four dominant schools of thought regarding its nature and composition, as follows: • The Dualist school sees the informal sector of the economy as comprising marginal activities—distinct from and not related to the formal sector—that provide income for the poor and a safety net in times of crisis (Hart 1973; ILO 1972; Sethuraman 1976; Tokman 1978). • The Structuralist school sees the informal economy as subordinated economic units (micro-enterprises) and workers that serve to reduce input and labour costs and, thereby, increase the competitiveness of large capitalist firms (Moser 1978; Castells and Portes 1989). • The Legalist school sees the informal sector as comprised of “plucky” micro-entrepreneurs who choose to operate informally in order to avoid the costs, time and effort of formal registration and who need property rights to convert their assets into legally recognized assets (de Soto 1989, 2000). • The Voluntarist school also focuses on informal entrepreneurs who deliberately seek to avoid regulations and taxation but, unlike the legalist school, does not blame the cumbersome registration procedures. Each school of thought subscribes to a different causal theory of what gives rise to the informal economy. • The Dualistsargue that informal operators are excluded from modern economic opportunities due to imbalances between the growth rates of the population and of modern industrial employment, and a mismatch between people’s skills and the structure of modern economic opportunities. • The Structuralists argue that the nature of capitalism/capitalist growth drives informality: specifically, the attempts by formal firms to reduce labour costs and increase competitiveness and the reaction of formal firms to the power of organized labour, state regulation of the economy (notably, taxes and social legislation); to global competition; and to the process of industrialization (notably, off-shore industries, subcontracting chains, and flexible specialization). • The Legalistsargue that a hostile legal system leads the self-employed to operate informally with their own informal extra-legal norms. • The Voluntaristsargue that informal operators choose to operate informally—after weighing the costsbenefits of informality relative to formality. The dominant schools of thought have different perspectives on this topic, although some do not explicitly distinguish between the two or adequately deal with both. • The Dualistssubscribe to the notion that informal units and activities have few (if any) linkages to the formal economy but, rather, operate as a distinct separate sector of the economy and that the informal workforce—assumed to be largely self-employed— comprise the less advantaged sector of a dualistic or segmented labour market. They pay relatively little attention to the links between informal enterprises and government regulations. But they recommend that governments should create more jobs and provide credit and business development services to informal operators, as well as basic infrastructure and social services to their families. • The Structuralists see the informal and formal economies as intrinsically linked. They see both informal enterprises and informal wage workers as subordinated to the interests of capitalist development, providing cheap goods and services. They argue that governments should address the unequal relationship between “big business” and subordinated producers and workers by regulating both commercial and employment relationships. • The Legalists focus on informal enterprises and the formal regulatory environment to the relative neglect of informal wage workers and the formal economy per se. But they acknowledge that formal firms— what de Soto calls “mercantilist” interests—collude with government to set the bureaucratic “rules of the game” (de Soto 1989). They argue that governments should introduce simplified bureaucratic procedures to encourage informal enterprises to register and extend legal property rights for the assets held by informal operators in order to unleash their productive potential and convert their assets into real capital. • The Voluntarists pay relatively little attention to the economic linkages between informal enterprises and formal firms but subscribe to the notion that informal enterprises create unfair competition for formal enterprises because they avoid formal regulations, taxes, and other costs of production. They argue that informal enterprises should be brought under the formal regulatory environment in order to increase the tax base and reduce the unfair competition to formal businesses. 3. Definition of Street Vendors: Street vendors are identified as self-employed workers in the informal sector who offer their labor to sell goods and services on the street without having any permanent built-up structure (National Policy on Urban Street Vendors [NPUSV], 2006, p. 11). Various studies have already confirmed the fact that street vendors comprise one of the most marginalized sections of the urban poor. Street Vendors play a very dynamic role in the urban economy, providing necessary items, which are largely both durable and cost-effective, to average income-earning households at cheap and affordable rates. In addition, they help many small-scale industries to flourish by marketing the products that they manufacture (Bhowmik, 2001; Tiwari, 2000). Thus, they help to sustain the urban economy to a great extent in terms of generation of employment and income, and provision of services to others. The policy document on street vendors documents….‘Street vendor’ is defined as ‘a person who offers goods and services for sale to the public in a street without having a permanent built-up structure.’ There are three basic categories of street vendors: a. Stationary; b. peripatetic and c. mobile, Stationary vendors are those who carry out vending on a regular basis at a specific location, e.g. those occupying space on the pavements or other public places and/or private areas either open/covered [with implicit or explicit consent] of the authorities. Peripatetic vendors’ are those use who carry our vending on foot and sell their goods and services and includes those who sell their goods on pushcarts. Mobile street vendors are those who move from place to place vending their goods or services on bicycle or mobile units on wheels, whether motorized or not, they also include vendors’ selling their wares in moving buses, local trains etc. 4. Women Street Vendors in India: Women also, for some reason, take to vending on streets. The reasons could be Lack of education, financial need, Family pressure or a combination of all these and many more. Being in an unorganized sector, lack of policies, law and regulations lead to certain difficulties during working. Women in particular, might face a set of consequences during work. Associations like National Association of Street Vendors of India [NASVI] and other local NGOs work towards the protection of street vendor’s livelihood. In 2010, the Supreme Court of India, recognized street vending as a source of livelihood, and directed the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation to work out on a central legislation [policy], and a draft of the same was unveiled to the public on November 11, 2011. The key point of the draft bill were, protection of legitimate street vendors from harassment by police and civic authorities, and demarcation of ‘vending zones’ on the basis of ‘traditional natural markets’, proper representation of vendors and women in decision making bodies, and establishment of effective grievance redressal and dispute resolution mechanism. In essence the policy on ‘Street Vendors’, was drafted to address their issues and concerns.As several of the issues and concerns this policy aims to address, have not been effectively addressed, this paper intends to evaluate some of the very important issues and concerns the policy on Street Vendors has attempted to address. These issues and concerns have been evaluated vis a vis the vending conditions faced by Women Street Vendors as it was found on a preliminary investigation that women street vendors are doubly disadvantaged; firstly, as they are women and secondly they are street vendors. For this purpose 235 women street vendors, vending in 3 districts of Karnataka were extensively surveyed using a well-structured questionnaire. Before, the results of the survey are discussed, for better understanding, it is intended that the focus of the policy on street vendors be provided. The major issues and concerns that policy on street vendors are provided in the following pages after providing the definition of street vendors by the policy document. 5. Provision of Civic Facilities : Municipal Authorities need to provide basic civic facilities in Vending Zones / Vendors’ Markets which would include: i) Provisions for solid waste disposal; ii) Public toilets to maintain cleanliness; iii) Aesthetic design of mobile stalls/ push carts; iv) Provision for electricity; v) Provision for drinking water; vi) Provision for protective covers to protect wares of street vendors as well as themselves from heat, rain, dust etc; vii) Storage facilities including cold storage for specific goods like fish, meat and poultry; and viii) Parking areas. The Vendors’ Markets should, to the extent possible, also provide for crèches, toilets and restrooms for female and male members. 5.1 Public Health & Hygiene Every street vendor shall pay due attention to public health and hygiene in the vending zone/vendors’ market concerned and the adjoining area. He/she shall keep a waste collection basket in the place of vending. Further, he/she shall contribute to/promote the collective disposal 5.2 Education & Skills Training Street vendors, being micro entrepreneurs should be provided with vocational education and training and entrepreneurial development skills to upgrade their technical and business potentials so as to increase their income levels as well as to look for more remunerative alternatives. 5.3 Credit & Insurance Credit is an important requirement in street vending, both to sustain existing activity and to upscale it. Since vendors work on a turnover basis, they often take recourse to high interest loans from non-institutional lenders. Although they usually demonstrate high repayment capacity, absence of collateral and firm domiciliary status usually debars them from institutional credit. State Governments and the Municipal Authorities should enable Self-Help Groups (SHGs) and organizations of street vendors to access credit from banks through mechanism like SHG-Bank Linkage. The TVC should disseminate information pertaining to availability of credit from various sources, especially micro-finance and should take steps to link street vendors with formal credit structures. Street vendors should also be assisted in obtaining insurance through Micro-insurance and other agencies. With respect to credit, the Credit Guarantee Fund Scheme for Small Industries (CGFSI), designed by the Ministry of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises, Government of India and the Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI) may be extended to the street vendors. This scheme aims at resolving the problem of collaterals, and inducing banks to gradually move away from a completely risk-averse stance toward small scale industries. The registration process undertaken by the TVC based on field surveys through professional institutions/agencies and the domiciliary status confirmed by them on the Identity Card as also in their records should make it possible to cover a large number of street vendors under institutional credit. 6. Results of the Survey on Street Vendors in Karnataka: In the backdrop of this policy on Street Vendors and particularly, it’s implicit expression on Women Street Vendors it is intended to discuss the results of the survey carried out to assess the issues and concerns of women street vendors in Karnataka. 6.1 Discussion on the Demographic profile of the women street vendor along with some of their basic issues and concerns: A total of 235 women street vendors spread across three districts of Karnataka viz., Bangalore, Bangalore Rural and Shimoga were surveyed for their issues and Concerns in the backdrop of the policy on Street Vendors by the Honorable Supreme Court of India. The tables provided as Annexures – 1 and 2 provide data on demographics of the surveyed population; it could be read from the tables that 179[76.2%] of the women street vendors of the total belong to Karnataka, 37[15.7%] of them belong to Tamil nadu and 17[7.2%] others belong to Andra Pradesh, Whereas 2 out of these 235 women street vendors belong to other states of India. One interesting aspect that could be noted from this data is that almost 23% of these vendors are from Tamil nadu and Andhra Pradesh, who are part of the larger migrated populations from these states into Karnataka. The age profile of the respondents show that 81.7% of the respondents are in the age group of 25 to 50 years, further this data shows a progressive decline of the number of street vendors as the age advances, a possible indicator that ‘street vending’ is a job capable for the people of the lower ages and not so for those who are older. The education profiles of the respondents show that out of the 235 street vendors, 177[75.2%] of them has education equivalent or lower than the 7th standard and the rest of the 28 of them have education up to matriculation; none of the street vendors surveyed had education above matriculation; a possible inference is that people in the informal sector with educational qualification above matriculation would not take to street vending and may take up other better employment within this sector. The family size of the respondents is surprisingly lower than what is normally expected of the lower income families; with almost 62% of the women street vendors living in family size up to 4 and up to 96% of them living in family size up to 7. One possible attribute to such lower size of the families is that the street vendors surveyed for this study are from slightly better off districts of Karnataka including the capital itself. The data on the number of earning members in the family indicate that about 55 of the surveyed 235 women street vendors are the sole bread winners of the family as against the popular belief that ‘men are the bread winners of the family’; the reason for these women to take up street vending is to earn a source of livelihood for the family. Another 150 women street vendor are accompanied by another earning member in the family; the very fact that in spite of another earning member of the family these women have taken to vending in the streets indicate that the ‘quantum’ of earning of the other earning member needs supplement and /or the other family member has taken to another occupation that supplements the income of the women street vendor. The annexure-2 of this paper provides data on other demographics and Descriptives about a few of the important variables considered for the study in the backdrop of the policy on street vendors. From the data on the duration work, a very disturbing trend could be noted; that number of women street vendors who have been vending for more than 10 years is 71[30.2%] and the number of women who have been vending in the streets for 5 to 10 years is 51[21.7%] whereas the women who have been vending in the streets for less than two years is 77[32.8%]. If one observes this trend in the table, it is quite clear that these 77 women who have got into vending for the last 2 years are the addition to the existing women street vendors, hence this clearly indicates that the number of women who have taken to street vending is higher in proportion to those who were existing in last 10 years or more. Or this data might actually be indicating that though higher number of women take to street vending they may not continue to do so; if this is true, the reasons for this would be well worth knowing. As regard the duration of time that these women vend in the streets; an interesting phenomena such as 65[27.8%] of the total of 235 women street vendors vend for 6 hours or less in a day; making vending almost a part-time employment. On the other side of the spectrum; the toil of street vending expressed in terms of 66[28.1%] of the 235 women street vendors vending for more than 10 hours in a day. The rest of the women street vendors that is, 104[44.3%] of them vend for anywhere between 6-10 hours in a day. The frequency with which these women street vendors need to replenish their stocks vary from Daily, Weekly and Monthly; while most of the women, 174[74.0%] out of the total 235 replenish their stocks daily, inferring that they deal with perishable goods, 52[22.1%] replenish their stocks on a weekly basis, whereas another 9[3.8%] women replenish their stocks monthly. So far these women doing another additional job to street vending is concerned; 214[91.5%] of the women street vendors out of the total 235 do not do another additional job, but exclusively engage themselves in Street vending, whereas 20[8.5%] of these, do an additional job to Street vending to supplement their incomes. One among the important provisions for these street vendors in the policy on Street vendors is the provision of public toilet for them; as regards this provision, in the survey it was asked whether they have access to a public toilet nearby, if not an exclusive access to the same; 56[24.7%] of these women reported that they do have access to some kind of public toilet facility, whereas a the majority of 179[76.2%] of them reported as having no access to the public toilet facility near the place of vending. 6.2 Additional following-up discussion based on the results on major issues and concerns of the women street vendors: The data from these 235 women street vendors across the four districts of Karnataka was subjected to simple statistical test of cross tabulation to further understand their issues and concerns with particular reference to the policy on Street vending by the honorable Supreme Court. The first of the cross tabulations to which the data was subjected was to evaluate if the place of vending has any bearing on these women street vendors being members of any of the street vending organisations. Table 1 representing this cross tabulation clearly shows that 190[80.9%] of these women are not members of any of the organisations representing the street vendors; whereas 45[19.1%] of them are members of one of the organisations representing the street vendors. Analyzing the data in the table further, indicates that among the four districts, in the district, Shimoga the women street vendors are far more organized than the remaining 3 districts; with about 45% of the women street vendors affiliating with one or the other organisations that represents them. It is rather surprising to find that the women street vendors from the capital Bangalore are not as organized as those of the district- Shimoga. The Pearson Chi-Square value of this cross tabulation 43.101at 3 degrees of freedom is significant at 5% level of significance with p-value =0.000 Further, it was intended to see if being members of any of the organisations help these women street vendors to be aware of their right to roadside vending. The table 2 shows the cross tabulation between the membership with the any of the street vendor’s organisations with that of the awareness to roadside vending. The table clearly shows that general awareness about roadside vending is abysmally low among the total of 235 surveyed women street vendors with as many as 189[80.4%] not being aware of their right to roadside vending while only 45[19.1%] of them being aware of this right. When this data is further analyzed, it is found that though the awareness of their right to vend at the roadside is low among both members of the organisations and non-members; about 30% of the members of street vending organisations are aware of this right whereas the same awareness among the non-members is about 17%. Such analysis lends to the thesis that being members of the street vendor’s Organisation help them on this awareness. The Pearson Chi-Square value for the cross tabulation between the membership with the any of the street vendors organisations with that of the awareness to roadside vending is 4.705 at 1 degrees of freedom and the same is significant at 5% level of significance with p-value =0.030 Besides awareness of road side vending and membership among street vendor’s organisations; the data among the street vendors from these four districts of Karnataka was cross tabulated for understanding the access to public toilets to these women with the place of vending. Table 3 shows the cross tabulation between access to public toilets to these women with the place of vending. On the lines of Descriptives observed with reference to the provision of public toilet facility to the women street vendors the cross tabulation in table 3 clear shows that 179[76.2%] of these women from all the four districts do not have access to public toilet facility; the Pearson Chi-Square value for cross tabulation between access to public toilets to these women with the place of vending is 36.305at 3 degrees of freedom and the same is significant at 5% level of significance with p-value =0.000 7. Conclusions: It is quite evident from the analysis above that these women street vendors still face a lot of issues and concerns particularly with respect to; working hours, public toilet facility, awareness about organisations that work for them and particularly membership to these organisations and about their rights on street vending. Further from the foregoing discussion it could be concluded that these women are generally illiterate and take to street vending mostly to supplement and /or compliment incomes for livelihood of their families. Some of them [as many as over 20% of these] are the single workers in the family and street vending is the means for them to subsist their families and also that they are the breadwinners of the family. Quit a few of these women[as many as 8%] do take up additional employment as street vending alone does not provide enough incomes to take care of their families requirements. The most important conclusion that could be derived from this study is that the policy on street vending is a non-starter in making lives of the street vendors a little comfortable than however cruel-some it is now as it has been for many years. Particularly women street vendors are doubly disadvantaged as it is natural for them to not only earn livelihood for their families but also rear their families to a meaningful existence. References: 1. Bhowmik, Sharit, K. 2001. Hawkers in the Urban Informal Sector: A Study of Street Vendors in Seven Cities. Patna, India: NASVI. 2. Bromley, Ray. 2000.” Street Vending and Public Policy: A Global Review.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 17. 3. Chen, Martha Alter. 2004. Rethinking the Informal Economy: Linkages with the Formal Economy and the Formal Regulatory Environment.”EGDI-WIDER Conference, September 17-18, Helsinki, Finland. 4. Chowdhury, Subhanil. 2011. “Employment in India: What Does the Latest Data Show?” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol. XLVI, No. 32 (August 6), pp. 23-26. 5. McKinsey Global Institute. 2010. India’s Urban Awakening: Building Inclusive Cities, Sustaining Economic Growth. 6. Krishnamurthy, J. and G. Raveendran. 2009. “Measures of Labour Force Participation and Utilization.” New Delhi: National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganized Sector. Shashidhar Channappa

Head, Department of Social work, The Oxford College of Arts, Bangalore. Veena K.N Associate Professor, Indus Business Academy, Bangalore. V.J. Byra Reddy Professor, University of Petroleum and Energy Studies, Dehradun. |

Categories

All

Social Work Learning Academy50,000 HR PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

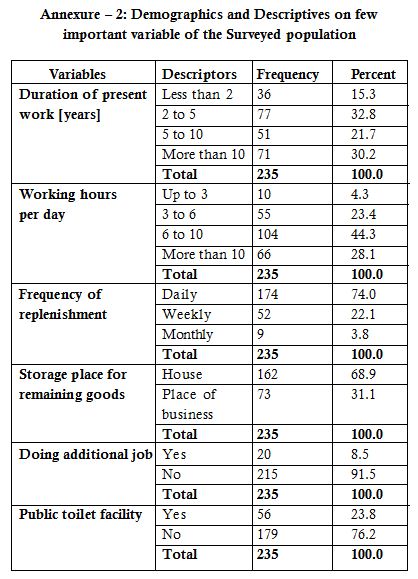

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS. MHR LEARNING ACADEMYGet it on Google Play store

|

SITE MAP

SiteTRAININGJOB |

HR SERVICESOTHER SERVICESnIRATHANKA CITIZENS CONNECT |

NIRATHANKAPOSHOUR OTHER WEBSITESSubscribe |

MHR LEARNING ACADEMY

50,000 HR AND SOCIAL WORK PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed