|

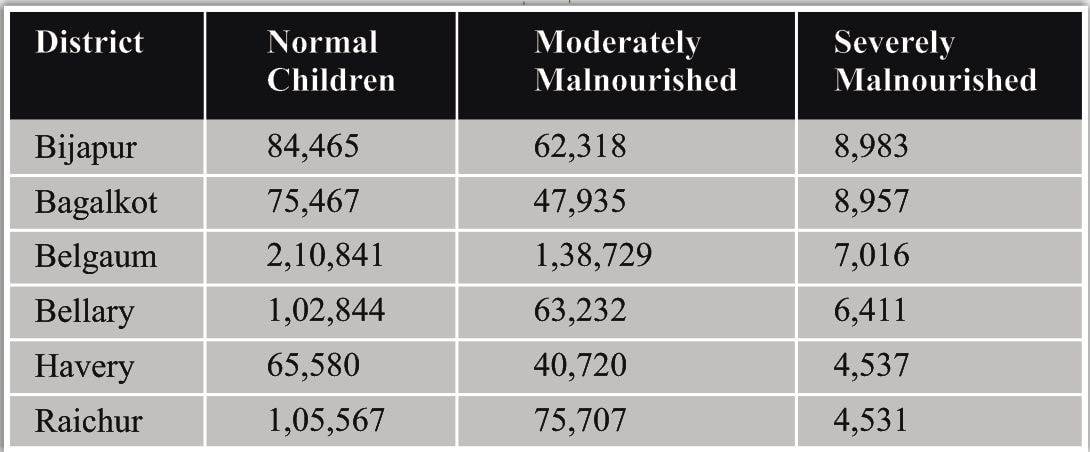

Thousands of malnourished children suffer in silence. And no one cares Something is not always better than nothing. Hungry little ones would rather sleep on an empty stomach than gulp down inedible ‘packet food’. The last time Mahadevi, 3, braved a mouthful of the disable bath (a rice dish) distributed at the anganvadi In Appanadodi, 25km from Raichur, Karnataka, she cried all night. “She had a terrible stomach upset,” says her mother, Narasamma. Given a choice, she would like Mahadevi to have rice, dal and roti every day. But with five children to feed and an income of Rs60 a day, the family has to make do with a handful of rice and chilli powder. “Why can’t the anganwadis give edible food?” asks Narasamma. The question has been raised many times over the last few weeks, since the death of a five-year-old boy in Raichur shortly after he was featured in a television news story on the shocking levels of malnutrition in the district. Further, the response to a recent query under the Right to Information Act reveals that death of children with thin limbs, sunken ayes and protruding bellies is not unique to Raichur, Bijapur, for instance, has 8,983 severely malnourished children as against 4,531 in Raichur. Children here, largely, fall into four categories: thin, thinner, thinnest and thinner than thinnest. The government classifies them as normal, moderately malnourished and severely malnourished.

Venkatesh, 3, of Raichur, falls in the last category. He is all of 9kg and, according to his mother, non-fussy about food. “Expect for the anganwadi packet food, which doesn’t get easily digested,” she says. Her eight-year-old daughter Jyothy is not even in the reckoning. Once a child is over six, the government is no longer bound to keep tabs on their growth parameters. The state department of women and child development (DWCD) says 38 lakh of 60 lakh children under age six in Karnataka are enrolled in anganwadis. Yet, Karnataka is home to 71,605 severely malnourished and 11, 29,947 moderately malnourished children. The official figures record 1,030 deaths due to malnutrition in 2008-09, 1,070 deaths in 2009-10, 1,144 deaths in 2010-11 and 431 deaths up to august 2011. Ranuka can barely control her tears as she speaks of her son Naveen Kumar, 6, who has lost his eyesight, can’t walk or talk, and is perpetually sick. At their modest home in Chikasugur, 9km from Raichur, it is impossible to guess that Manushree is the younger sibling. At three, she is no more than double Naveen’s weight. “I don’t know what went wrong,” says Renuka. The District Legal Services Authority (DLSA), chaired by Raichur sessions judge S.N. Kempagouder, knows exactly what went wrong. After a thorough Investigation of the malnutrition cases in Raichur, as directed by the High Court, the DLSA has come to the conclusion that children like Naveen are victims of consanguineous marriages. Add to that conspiring factors like early childbirth, superstitious beliefs and illiteracy, and the mystery is solved! The victim is the culprit! “Isn’t it too convenient?” asks Y. Mariswamy of Samajika Parivarthana Jana Andholana, a people’s rights group. “The Supreme Court has stated that anganwadis must serve freshly- prepared local food. Why is the Karnataka government serving packet food, while other states follow the court directive?” The contract for the food supplies to more than 60,000 angawadis, it turns out, with a single Tamil Nadu- based private company, Christy Friedgram Industry. “There is something clearly amiss here. The government officials on many occasions have made it clear that the contract will stay, no matter what,” says Akkhila Vasan, public health researcher, Janaarogya Andholana Karnataka. As of now, anganwadis in Karnataka serve bisibelebath, Kesaribath, l nutria corn pop and energy food that come in packets of half a kilo or one kilo. “Three-our years ago, we used to feed freshly-prepared food to children. It was definitely healthier and tastier, “says Rangalaxmi, an anganwadi worker at Raichur. The 15-member committee formed, as per the court directive, to look into the matter has decided to supply egg and milk to children in Raichur. The last time there was a similar proposal, it was opposed tooth and nail by the puritans. The committee is also exploring the possibility of supplying sprouts, groundnut, Jaggery and semolina of children across the state. At the inauguration of a nutrition rehabilitation center at the district hospital in Bijapur recently, it was decided to schedule a pediatrician’s visit weekly at the 10 anganwadis in the district. “We have only one paediatrician per taluka on an average. He can’t look at all cases,” argued a district health official. “Get local private practitioners then. If we implement it for a month on a trial basis and show the court improved results, the plan could later be implemented at all anganwadis across the state, “says UshaPatwari, joint director, DWCD, Bangalore. The nutrition rehabilitation centers, started on a pilot basis at Bijapur and Gulbarga, are expected to save lives. Like Shreekanth, the 18- month –old Sindgi boy, who weighted 5.5kg before he was admitted to the centre in Bijapur.Within 10 days, he gained a kilo, courtesy the regular intake of bananas, milk, rice, dal, vegetables, chapatis, ragi and boiled eggs. HALL OF SHAME The official figures on the number of children, zero to six years, in the worst performing districts in the state: “The nutrition intake is in keeping with the WHO guidelines,” says Vidya Pandey, nutritionist at the Gulbarga centre. Started in march, 10-bed center has already rehabilitated 150 severely malnourished children. The Bijapur centre, a visit reveals, has only one patient and nice empty beds. The inauguration was actually an attempt to revive the centre which has been wasting for about a year. “We don’t have a nutritionist here and the primary health centres hardly refer any cases,” says a nurse. Sitting in her Chikasugur hamlet, with just –born twins weighted less than 2kg each, Narasamma is absolutely clueless about the future. Her five–year–old son keeps falling ill. She doesn’t have the luxury to mull over her own failing health. “The problem begins with the low nutrition levels of expectant mothers,” says Dr T. Chandrika, an obstetrician at a private hospital in Basavanagara, Raichur. Ninety percent of the pregnant women here, she says, are anemic, with hemoglobin levels of less than 10, and the chances of having a healthy baby are suspect. “Both from the point of view of international legal commitments undertaken by the Indian state as well as from a constitutional point of view protection of children from malnutrition, particularly of those below the age of six, is mandatory,” says advocate Clifton D’Rozario, adviser to the commissioners of the Supreme Court . According to the latest National Family Health survey, the Maternal Morality Ratio in Karnataka is 213 and Infant Mortality Ratio is 45 for every 1,000 live births. The Human Development Index 2011 released by the United Nations Development Programme ranks Karnataka among the worst performers with a Hunger Index of 23.7, now here close to the best performing state, Punjab, with a HI of 13.63 Kerala (17.6) Tamil Nadu(20.8) and Andhra Pradesh, (19.5) fare better. Rural development Minister Jairam Ramesh is perplexed to find “the rate of malnutrition so high in pockets of growth like Gujarat and Karnataka”. Ambanna Arolikar, a Raichur social worker, is not, “this is what happens when corruption seeps into the very fabric of society,” he says. He would like people to think of Raichur as home to India’s only active goldmine, Hutti, in Lingasugar. “Maybe once our children get justice,” he says. Aolikar is hopeful. Wonder is Divyashree, 3, knows what hope is. She barely weighs 4kg and is totally dependent on her sister Ashwini, 11, who had to drop out of school. Their mother, Mahadevi, works on a farm at Chikasugur from 10 am to 8 p.m. The girls stay in the 10x12ft mud house all day. There is some rice cooked for the two. They like it with chilli powder. On an impulse, I pull out some chocolates from my bag. Ashwini smiles as she feeds her sister; Divyashree starts crying as she sucks on the chocolate. “She likes it,” Ashwini says, assuringly. Justice is nowhere in sight. Jisha Krishnan (Courtesy: The Week, December 4, 2011) This story of agony of Karnataka published in Kerala was brought to our notice by L.K. Mahapatra, Celebrated Anthropologist from Odisha |

Categories

All

Social Work Learning Academy50,000 HR PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS. MHR LEARNING ACADEMYGet it on Google Play store

|

SITE MAP

SiteTRAININGJOB |

HR SERVICESOTHER SERVICESnIRATHANKA CITIZENS CONNECT |

NIRATHANKAPOSHOUR OTHER WEBSITESSubscribe |

MHR LEARNING ACADEMY

50,000 HR AND SOCIAL WORK PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed