|

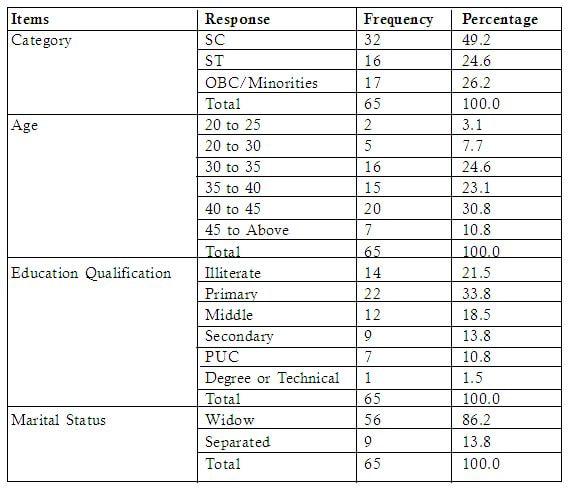

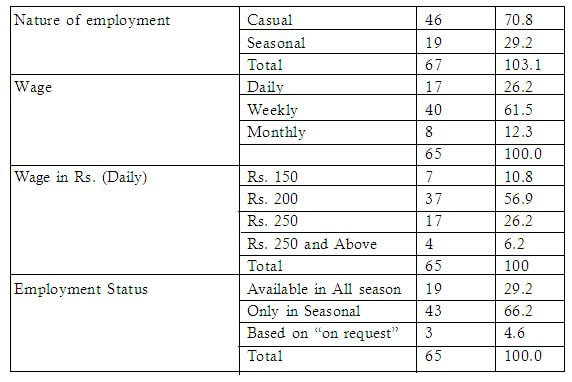

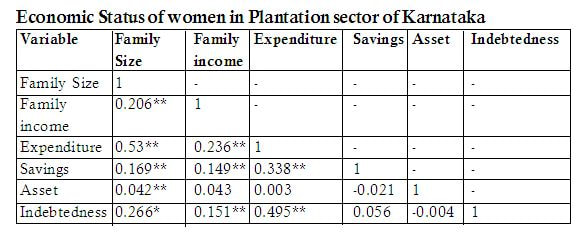

Introduction Gender norms and patterns are rigid, and very often put women in disadvantaged positions relative to men – including limiting women’s equal access to decent work. But gender norms can and do change. Economic policies – at the macro, meso and micro levels – can be designed in ways that are transformative and that enhance gender equity. The ability of paid employment to expand women’s range of choices – hence contributing to closing persistent gender gaps in labour markets and within households – is related to the type of jobs women have access to, the level and regularity of their earnings, the opportunities for mobilizing and organizing, and the ways in which women’s and men’s productive and reproductive roles are coordinated and protected through policies. Gender based deprivations and inequalities; poverty can be very debilitating and add on to the vulnerabilities of women. Another significant issue is regarding the fact that experiences and responses to poverty are dissimilar among men and women, due to the gendered constraints and variations in the opportunities (Masika, et al., 1997; Razavi, 2000). Poverty and Gender The analysis of poverty from a gender perspective develops both concepts to help understand a number of processes inherent to this phenomenon, its dynamics and characteristics in specific contexts. It helps to explain why certain groups, by virtue of their sex, are more likely to be affected by poverty. Gender dimensions of poverty often gain significance from the notion that women constitute the poorest of the poor, being the lowest in social and economic hierarchies. However, gender and poverty are two distinct forms of disadvantage and therefore, collapsing them into a ‘feminisation of poverty’ notion of women as the poorest of the poor is not adequate (Jackson and Palmer – Jones, 2000), average wage rates are lower for women among the casual workers (Sundaram, 2001). Poverty affects men and women in a differentiated manner. They identified a series of phenomena within poverty that specifically affected women and showed that poor women outnumbered poor men, that women suffered more severe poverty than men and that female poverty displayed a more marked tendency to increase, largely because of the rise in the number of female -headed households. This set of phenomena came to be termed the “feminization of poverty”. Women dedicate more time for not paid activities than men in house. Women have longer working hours, which is harmful to their health and nutrition. And in the employment perspective, women spent less hours performing paid work than men, they spent more on domestic tasks and they had a longer working day than men (Milosavljevic, 2003). Rationale of the Study Women workers in agriculture are more likely to be working at home. They are also more likely to be engaged in sub-contract work on a piece-rate basis in unorganized sector. Both these factors – their location of work and the nature of the contract arrangements – make these women open to exploitation as workers. This large proportion of women in home-based sub-contract work is a classic recipe for poverty. One of the main areas where poverty is generated is among such home-based workers in the manufacturing sector. In plantation sectors women are engaged larger than men, they have to work in plantation as well as in home. There is no studies was found to investigate gender poverty in plantation sector, this study investigates the poverty among female headed household in plantation sector of Karnataka. Material and Method The purpose of the study was to know the economic condition of women in plantation, and to understand the gender perspective of poverty in plantation. Researcher used descriptive research design, in the study researcher focused that there are two kinds of employment available in the plantation sector casual or contract labour and permanent employment. In casual employment provides low and irregular income, lack of social security, little regulation in work, and absence of legal protection. To meet goal of study the researcher selected only coffee and tea cultivated area in Karnataka, i.e., Kodagu, Chikkamagaluru and Hassan (Sakaleshapura). Researcher selected purposively only women headed family as samples and the total size of samples is 65 based on Morgan’s sample survey calculation with 5.0 percentage of significance level. Structured interview schedule was adopted by the researcher and descriptive statistical analysis was used with help of SPSS 17.0. Results Nature of Household The above table reveals that demographic profile of female headed households’ status working plantation area. Majority of women belongs to vulnerable communities (SC – 49.2, ST - 24.6) and the mean age of women household in plantation sector was 35. And majority of women were obtained less education qualification and in the view of marital status majority 86.0 percentages are widows on 13.9 percentages women were living separately with their children. Educational attainment levels among usual principal and subsidiary status workers reveals the clear extent of deprivation and resultant vulnerabilities with which most poor women function within the labour markets. Majority of women household members were depended on seasonal employment of plantation and majority of them (61.5 Percentage) were receiving wage in weekly based and the average wage of women is 200 rupees and the availability of employment in plantation only in seasonal period. The share of regular employment in plantation sector remains very low both for women and men. The access of women to regular employment remains at the low end. The better off sections manage to benefit from such access to regular jobs much more than the poorer households. This leaves casual labour as the only livelihood resort for most of the poor. It is often lamented that the opportunities in the casual labour market are the least desirable. In the wage perspective women were receiving less compared male labours in plantation sector. Household income is the most important component in terms of which the economic status of the household is studied. Income of the household, size of the family, expenditure, savings, assets, and indebtedness are the items to determent the economic status of the women household in the plantation. In order to examine the degree of significance among the above said variables, the correlation coefficient technique has been adopted. It is evident from the above table that the degree of associates were quite high at 1 percentage level of significance for the variables family size and family income (0.2060**), family size and savings (0.1697**), family size and indebtedness (0.2664**), income of the family and expenditure (0.2364**), income and savings of family (0.1491**), family income and indebtedness (0.1513**), total expenditure and savings (0.3381**), and total expenditure and indebtedness (0.4959**). The size of the house hold is positively correlated with income of the family, total expenditure, savings and indebtedness, the family income, i.e., the household income also positively correlated with total expenditure, savings and indebtedness and total expenditure of the family also positively correlated with savings and indebtedness. Women working in plantation sector lead her family with own earnings; the gender perspective on poverty status among women in plantation sector was examined in different perspective.

Measuring unpaid labour of women in Plantation Sector Unpaid labour is a key concept in the analysis of poverty from a gender perspective. The researcher gave an attention has also to the close relationship between unpaid labour and the ways in which women become poor, and to the need to measure such labour. The calculation of household work would also mark an important difference in household incomes between male -headed households that have a person devoted to domestic and care giving tasks and female -headed households without such a person, which assume the private costs imposed by this work. It has found that majority 92.0 percentages of female engages both paid work in plantation more in house without payment. And in duration of working in domestic nature is higher than paid work in plantation. By accounting for the time invested in each of these tasks, they can be made visible so that society can appreciate them and perceive gender inequalities in the family and in society. What is more, this time allocation serves to calculate total workload, a concept that is inherent to both unpaid and paid labour. Conclusion One of the invisible major challenges in plantation sector is women poverty. Keeping this issue in mind, the government will have to frame suitable policies to enhance the economic status of rural poor women in particular. Government should enlarge assisting hand to the women working as a casual or seasonal worker in plantation through welfare boards. Study also highlights policy interventions that are require to correct the imbalance. Steps have to be taking to create a well defined structure with which the diverse activities of these may be performed. References

Saravana K Research Scholar Dr.Lokesha M.U Assistant Professor, Department of Studies and Research in Social Work, Tumkur University Sashikanth Rao Research Scholar, Department of Studies and Research in Social Work, Tumkur University |

Categories

All

Social Work Learning Academy50,000 HR PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS. MHR LEARNING ACADEMYGet it on Google Play store

|

SITE MAP

SiteTRAININGJOB |

HR SERVICESOTHER SERVICESnIRATHANKA CITIZENS CONNECT |

NIRATHANKAPOSHOUR OTHER WEBSITESSubscribe |

MHR LEARNING ACADEMY

50,000 HR AND SOCIAL WORK PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed