|

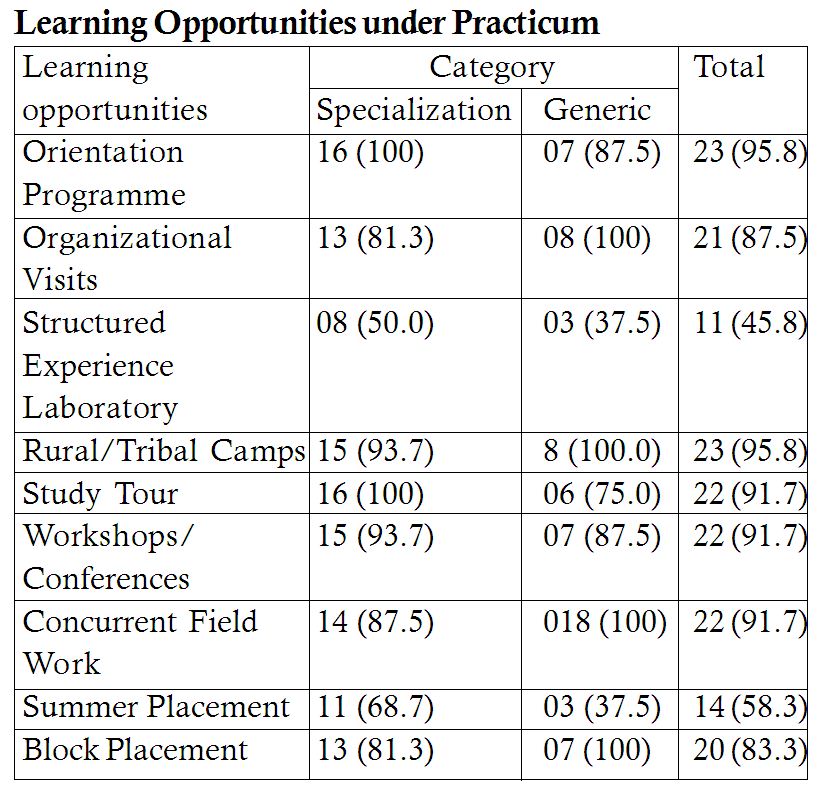

Introduction Field programmes are finally capturing the limelight in social work education as the “signature pedagogy,” a form of education that integrates theory and practice. Field education is an experiential form of teaching and learning that takes place in a service setting. Learning is achieved through the provision and/or development of services to clients, groups, communities, organizations, or the society. Field instruction is a process that involves the field instructor and the student in analyzing and integrating practice skills with the knowledge and value base of the profession. The goal is to develop the student’s competence in the practice of social work. The attempt to forge a strong link between theory and practice remains a cornerstone of social work professional education. Through the practicum, graduate students are provided with significant integrative experiences in preparation for their professional careers. The supervised practice experience or practicum is referred to in many different ways including “field instruction,” “supervision,” “placement” or “internship. The practicum, field instruction and field work are different terms used to denote the same reality i.e., the practicum in social work education (Philomina, 1978). Field instruction has always been a major part of social work training. Its history goes back to the days of the Charity Organization Societies in the last quarter of the nineteenth century when students learned social work by apprenticeship. Through “applied philanthropy” students obtained firsthand knowledge of poverty and adverse social conditions. With this apprenticeship model, training emphasized doing and deriving knowledge from that activity. By the end of the nineteenth century, social work was moving away from the apprenticeship model. The first training school for social work was a summer programme that opened in 1898 at the New York City by Charity Organization Society. In 1904, the society established the New York School of Philanthropy, which offered an eight-month instructional programme. Mary Richmond, an early social work practitioner, teacher and theoretician, argued that although many learned by doing, this type of learning must be supplemented by theory. At the 1915 National Conference of Charities and Corrections, presenters emphasized the value of an educationally based field-practice experience, with schools of social work having control over students’ learning assignments. This idea put schools in the position of exercising authority over the selection of agencies for field training and thus, control over the quality of social work practice to which students were exposed. Early in social work education, a pattern was established whereby students spent roughly half of their academic time in field settings (Austin, 1986). This paradigm was made possible by the networking that emerged from the early organizational efforts of social work educators. For instance, in 1919 the organization of the Association of Training Schools for Professional Social Work was chartered by 17 programmes. Thirteen of the original 17 schools were associated with universities or colleges at the post baccalaureate level by 1923. The American Association of Schools of Social Work, in its curriculum standards of 1932, formally recognized field instruction as an essential part of social work education (Mesbur, 1991).During the first part of the twentieth century, psychoanalytic theory dominated social work education. This influence tended to focus the attention of students and social work educators on a client’s personality rather than on the social environment. The depression of the 1930s and the enactment of the Social Security Act of 1935 brought about major changes in the United States’ provision of social services and need for social workers. Subsequent amendments to this act created several social welfare programmes and social work roles. From about 1940 until 1960, an academic approach dominated social work education. This approach emphasized students’ cognitive development and knowledge-directed practice. Professors expected students to deduce practice approaches from classroom learning and translate theories into functional behaviours in the field (Tolson& Kopp, 1988). Educational standards for field instruction were refined in the 1940s and the 1950s, and field work became known as field instruction. The American Association of Schools of Social Work took the position that field teaching was as important as classroom teaching and demanded equally qualified teachers and definite criteria for the selection of field agencies. In 1951, the Hollis-Taylor report on the state of social work education in the United States asserted that “education for social work is a responsibility not only of educators but equally of organized practitioners, employing agencies and the interested public. Widely accepted by the profession, this assertion became the cornerstone of all subsequent developments” (Kendall, 2002). In 1952 the Council on Social Work Education was established and began creating standards for institutions granting degrees in social work. These standards required a clear plan for the organization, implementation and evaluation of both in-class work and the field practicum. Interestingly, it was not until 1970 that field work was made a requirement for undergraduate programmes affiliated with the Council. The articulated approach characterized the third phase in the history of social work field instruction (from about 1960 to the present). This method integrates features from both experiential and academic approaches. It is concerned with a planned relationship between cognitive and experiential learning and requires that both class and field learning be developed with learning objectives that foster their integration. It does not demand that students be inductive or deductive learners but expects that knowledge development and practice will be kept close enough together in time to minimize these differences in learning style (Jenkins &Sheafor, 1982). Students may not be aware of the tensions and strong disagreements that have existed in previous years over the purpose of field education. When social work programs were housed in other disciplines, academically minded social scientists sometimes argued that the function of field instruction was to allow students to observe and collect data on poverty and social conditions first hand. The emphasis was often on the study of social problems. Students were not expected to provide services or assist clients. Agencies, of course, wanted students to roll up their sleeves and pitch in and help with the work that they were doing. As social work has matured as a unique discipline, a view of field education has emerged that blends both the academic and experiential perspectives. The 2008 Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards highlight the role of field education as “to connect the theoretical and conceptual contribution of the class room with the practical world of the practice setting” (CSWE, 2008). Both classroom and field are of equal importance for the development of the requisite competencies of professional practice. Social work programmes are free to use creativity in ensuring that their students develop the required competencies. Therefore, there may be differences in the design, coordination, supervision and evaluation of students’ field experiences. Rothman, (1971) made the point that the history of professional education in the U.S. has been characterized by a gradual transfer of responsibility from the practice settings to formal educational institutions. The apprenticeship model of learning has gradually been replaced by a formal, standardized structure. Participation in a degree programme, generally delivered within post-secondary educational institutions, is increasingly a requirement for recognition as a professional. Social work education has proceeded in this general pattern but has not followed the approach of professions that consign internship or practical experience to the last phase of formal training. Instead, social work educators were among the early defenders and definers of experiential education. They saw fieldwork as a concurrent adjunct to classroom instruction; a sort of laboratory for the curriculum. The philosophies like social justice, equality and empowerment resides deeper in the consciousness of a social worker when you are made to expose yourself to the situation directly or indirectly in social work education this constantly occurs because of practicum. Practicum is a learning experience and not a working experience. The main task in social work education, says the report of a training council working group is ‘to equip students with the knowledge and skills essential to effective social work practice’ (CCETSW, 1975). All social work behaviour is a process of making choices: some become self-evident and semi–automatic to the experienced professional social worker, but represent a long development of value selection on the part of many practitioners, with which each new entrant must experiment and whose validity he must discover for himself. The crucial distinction is that the skill in a professional are based upon a fund of knowledge that has been organized into an internally consistent body of theory and that this theory plus values and ethics then directs the differential applications of skill. This study makes an effort to explore and describe the contribution of practicum in social work education to develop knowledge, skill and value of students to become professionals. The Patterns of Practicum The nine learning opportunities in practicum are designed to provide variety of opportunities to develop and enhance professional practice skills. Learning is aided through observation, analysis of social realities and experiences of participation in designing and providing social work intervention. The tasks are organized to help the learner acquire beginning skills, practice those already acquired and master them from simple to complex. The learner is gradually encouraged to becoming an independent worker (UGC, 2001). UGC has designed the nine different sets of opportunities in social work practicum. They are:

Need and importance of the study All enduing professions adapt to social change and pursue their interest, but they maintain the same purposes at the core. Social workers are concerned with……? With what? With people? Psychological functioning? Delivery of social services? Management of human services? Policy analysis? Social change? …All of these or some of these? A profession is an occupation which requires a higher educational qualification, diploma or certificate. In social work education with certificate, there is code of ethics which is different in its content and core of whole profession. Can two year post graduation course of social work make professional social workers with a value system stated in code of ethics? Social work education comprises of a theoretical component taught in the classroom and field based education involving integration of the academic aspect and practice. Practicum is one of the most exciting and exhilarating parts of a formal social work education. It is also one of the most challenging. It allows students to put into practice the concepts, theories and skills they have learned in the classroom and it gives them room to explore and grow as budding social work professionals. However, the reality at schools of social work as Kaseke (1990) observes, is that fieldwork is marginalised when compared to its academic counterpart. The areas of knowledge covered in social work are so broad even before the student is able to understand basic concept of human behaviour, we teach methods and techniques of social work with social work practicum. Hardly students get total of 120 days’ class including social work practicum. In a study of the number and type of reported studies covering field education (Smith, 1981), it was found that there were few empirical studies of fieldwork and of field education generally, and fieldwork education was not strongly featured as part of social work knowledge building. Research Methodology The main aim of the study is to identify the new facts and realities of various schools of social work with regard to the implementation of practicum in postgraduate social work education in Karnataka. This study is descriptive in nature. The universe of the study constitute of schools of social work in Karnataka which consists of head of the departments, educators, students and agency supervisors. Objectives of the Study

Results and Discussion Profiles of Respondents The respondents who participated in the current research comprised of head of the departments, faculties, students and agency supervisors. The profile of respondents clearly shows that most of the faculties are female but departments are headed by males. Though majority of social workers are women the administrative enclave in many social work agencies and educational institutions has been disproportionately male (Snakas, 1977).Educating supervisors to supervise remains a problem even today in India because 59% of faculties and 57.7% of agency supervisors have not undergone any kind of training programmes for supervision. The academic qualifications of faculties vary a lot with minimum professional experiences. Majority (98.8%) of faculties have only minimum qualifications i.e., post-graduation in social work. Profiles of Schools of Social Work Social work in India is organized mostly at the masters’ level only 20.8% percentage of colleges offer under graduation in social work education. The second UGC review committee has suggested that it is better to complete much of social work education at a lower level in the educational ladder pointing to the need for introducing more bachelors’ programmes and other training programmes. Majority (62.5%) of the institutions providing post-graduation in social work are affiliated private colleges. Data clearly indicates that post-graduation in social work is offered with other courses by private colleges. The second UGC Review Committee asks to reconsider the general tendency for mixing up other courses with social work education as it tends to dilute the academic atmosphere bringing down the value of social work values.Maximum students get exposure to specialization pattern of education and it clearly indicates that student don’t have clarity about the concept of specialization and generic. Whereas other professional specialists become expert by narrowing their knowledge parameters, social workers have to increase theirs (Meyers, 1976) are as relevant as ever. Macro Perspective of Practicum Training in Social Work Education in Karnataka Administrative Functions Lack of formal structure for implementation of practicum makes the role of practicum substandard. Social action is one of the important methods which whole the nation is in need of it, but faculties don’t teach this method. So, we have failed to react to the realities of present situation and students are not sensitized towards problems. Most of departments (41.6%) have only one faculty for 30 students for supervision. Less student teacher ratio creates atmosphere of high accessibility to the students. Social work educators and administrators shoulder the paramount responsibility of selecting the most suitable candidates for social work programmes and providing students with the best education and training. The study makes clear that there is no proper base or procedure to admit the students to social work course and admission procedure followed are not uniform among the departments. Departmental Committee Social work institution should commit themselves to promoting social and economic justice for poor and oppressed populations and enhancing the quality of life for all. In order to strengthen linkages and partnership between the department of social work, field instructors and community agencies, a departmental committee has to be established. The study identifies that 45.8% departments of social work don’t have formal committee to coordinate whole system of practicum and students are also not aware of the committees. Planning for practicum is entirely an internal affair with no agency involvement of non-faculty personnel in 76.9% of the departments. Pattern of Practicum in Schools of Social Work in Karnataka Most of the departments (75%) adopted field based training method for training students in practicum. Sources widely agree that agency based practice learning offers potentially rich and valuable opportunities for applying and developing knowledge and skills (Whittington, 2007) but in contrast the study of Philomina (1978) clears that effective functioning in social work depends upon the practice of methods. In reality, there are no such agencies that can provide this opportunity. Most of the faculties (79.5%) stated that the content and training approach of two schools are similar but the degrees of skill demonstrated by the students are entirely different. So, quality of practicum is of great concern; however uniform field instruction methods have not been established. The study found that the institutions covered in the study did not have a comprehensive fieldwork curriculum. The Second UGC Review Committee also recognizes that field work faces another set of problems when it comes to recognizing it as a valid component of the professional curriculum. Practicum with nine learning opportunities is designed by the UGC to provide variety of opportunities to develop and enhance professional skills. The tasks are need to be organized to help the learner acquire beginning skills, practice those already acquired and master them from simple to complex. So, faculties and students were asked to rank the opportunities both ranked concurrent field work has been one with 63.71 and 57.52 garrets mean score. The ranking by students clearly shows that concurrent field work as most important one in practicum and they ranked structured experience laboratory as nine because in most of the college it has not been part of their practicum curriculum.

Suggestions

Conclusion Social work is mainly ‘invisible’ work (Pithouse, 1998:5).Given the reality of injustice in the world, the social work profession is challenged to create educational communities that prepare all members to participate in the promotion of social justice and the liberation of the oppressed. Another important issue is that academic units will be challenged to balance quality with quantity in the coming years. References

Dr. Ramesh B Associate professor, Department of studies and research in social work, Tumkur University, Tumkur, Karnataka. Sridevi.K. Assistant Professor, Department of Social work, Alva’s College, Mudabidire, Karnataka |

Categories

All

Social Work Learning Academy50,000 HR PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS. MHR LEARNING ACADEMYGet it on Google Play store

|

SITE MAP

SiteTRAININGJOB |

HR SERVICESOTHER SERVICESnIRATHANKA CITIZENS CONNECT |

NIRATHANKAPOSHOUR OTHER WEBSITESSubscribe |

MHR LEARNING ACADEMY

50,000 HR AND SOCIAL WORK PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed