|

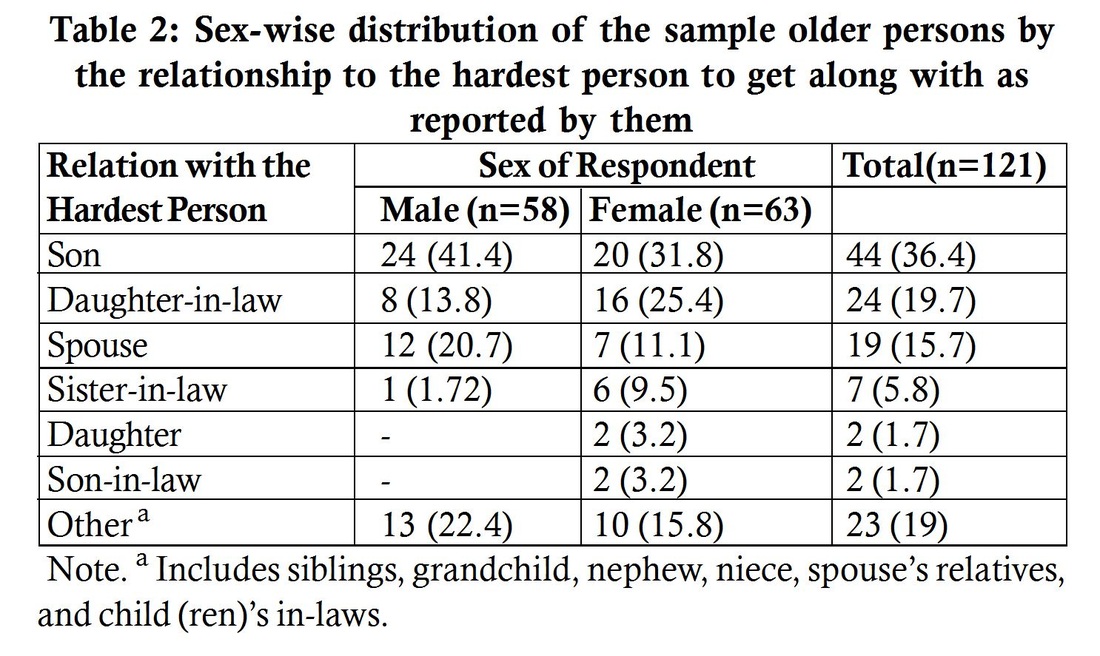

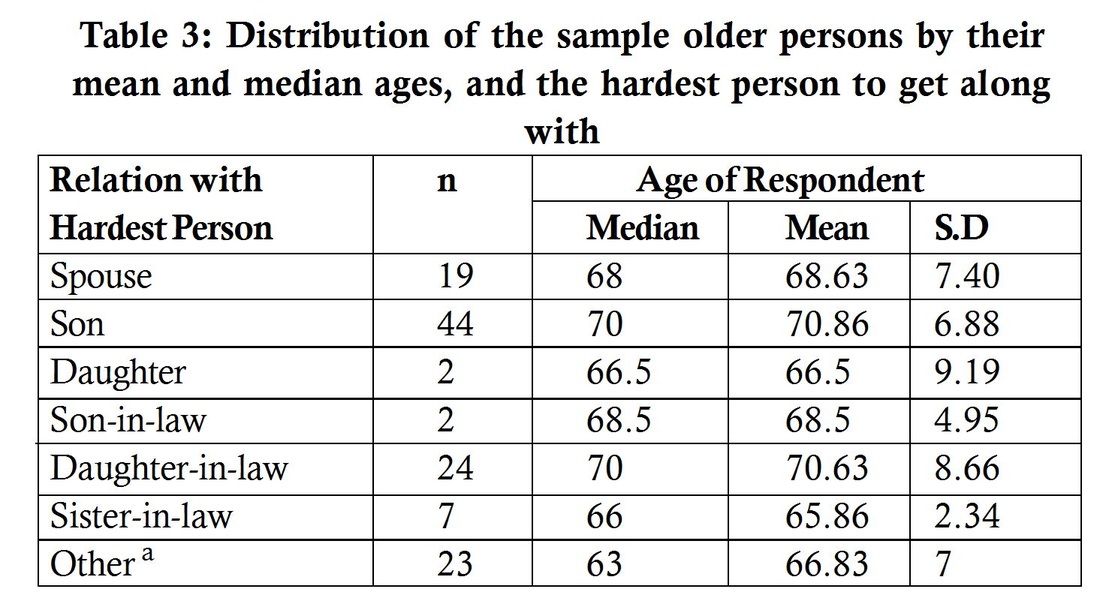

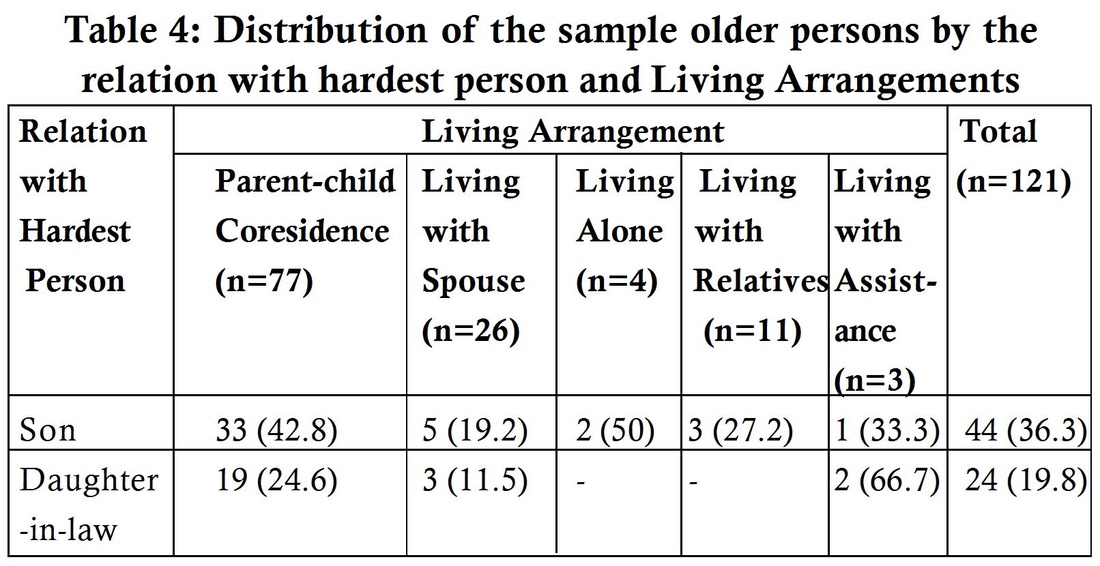

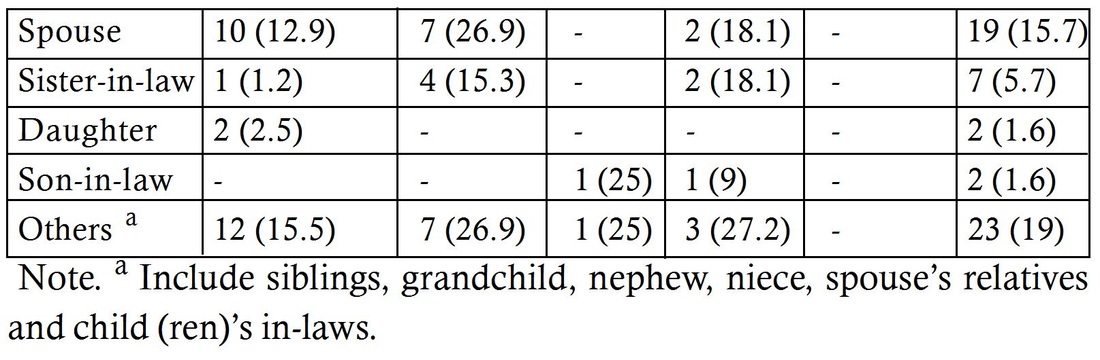

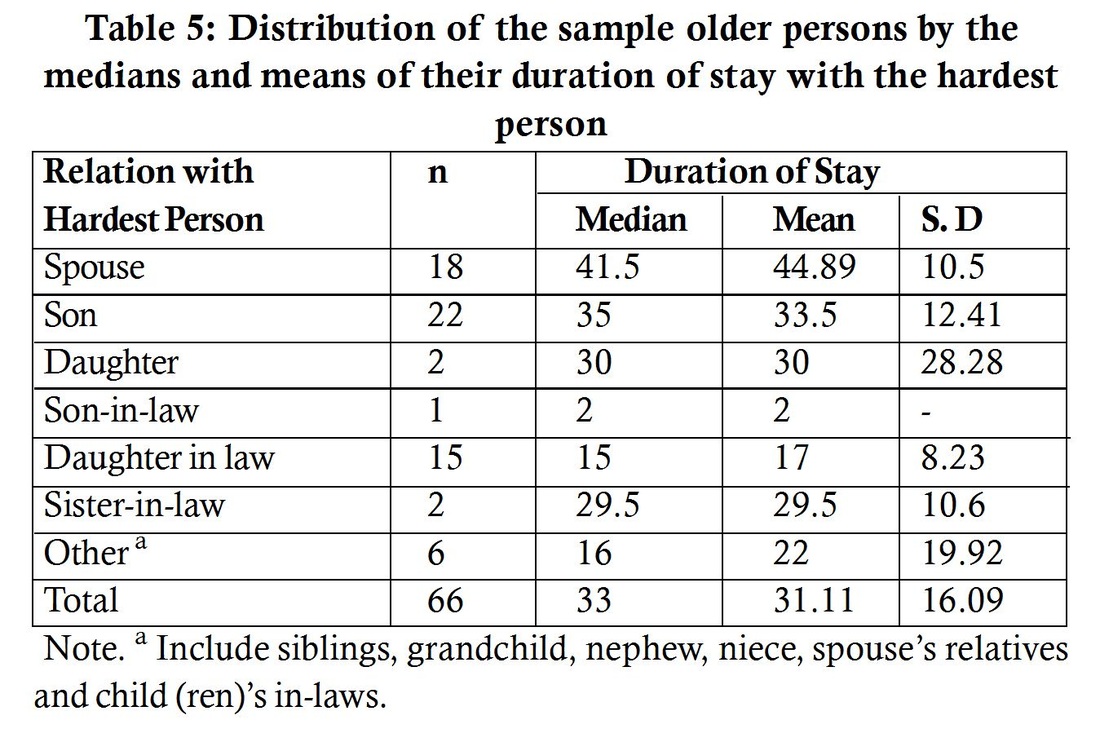

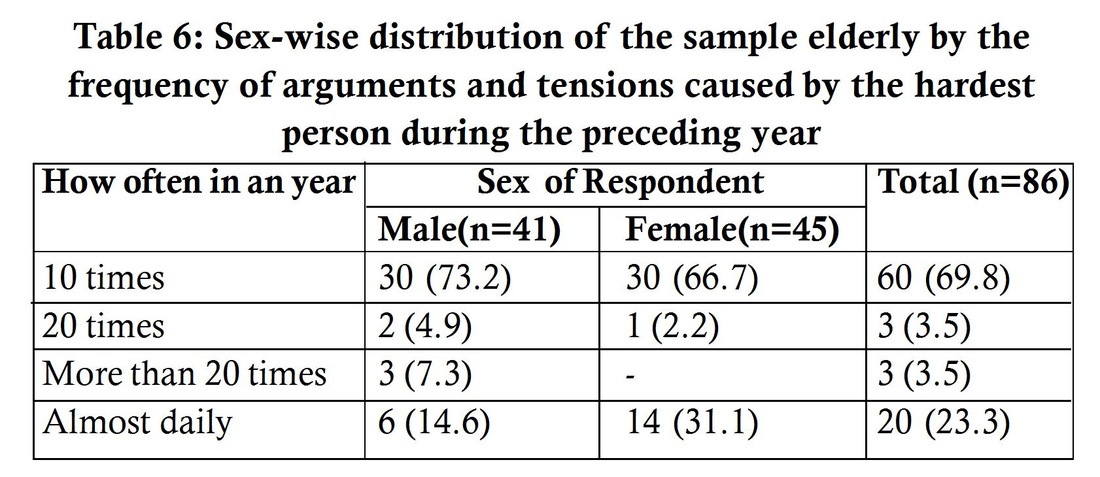

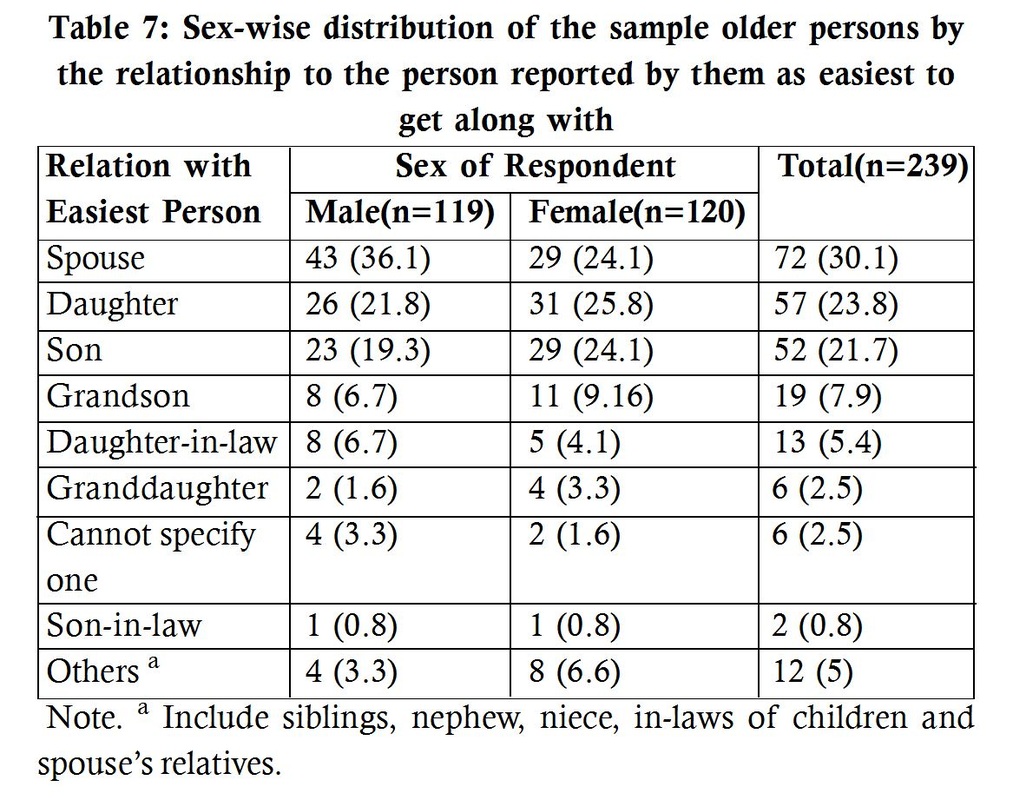

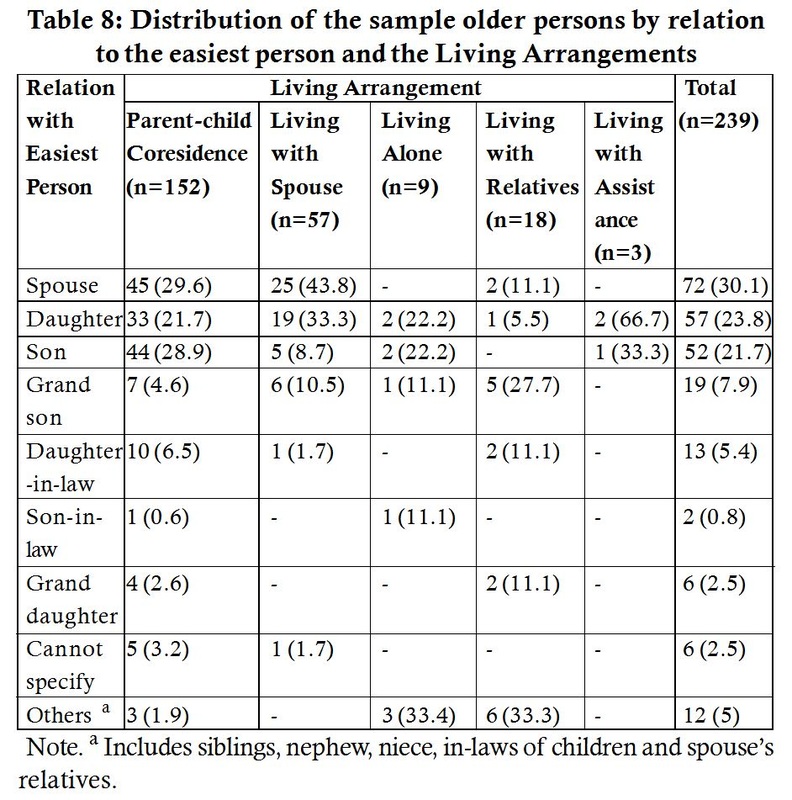

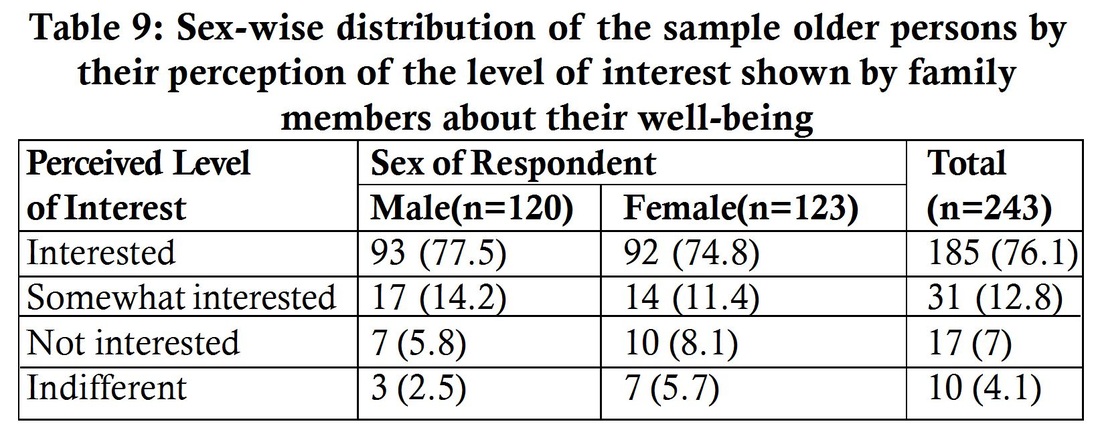

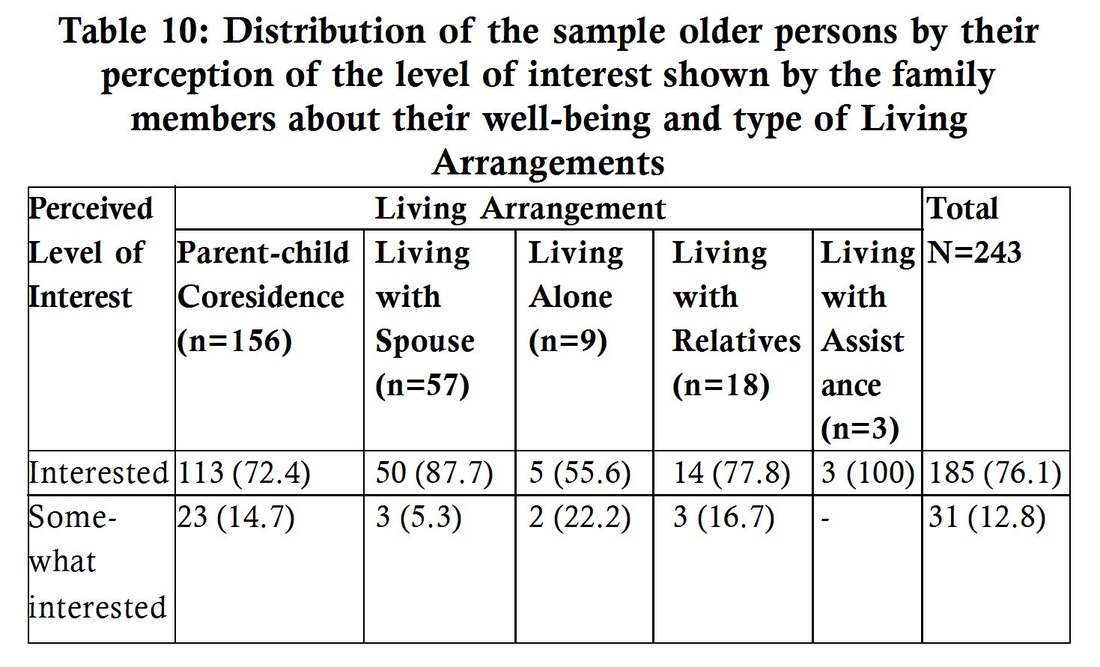

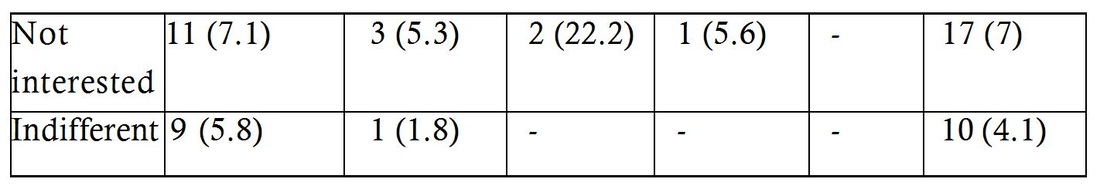

Abstract The ageing scenario in India has transformed in the recent decades due to the observed demographic trends among the older population and rapid social change that has led to the decline in informal supports for older persons within the family, which may be adversely affecting their well-being. In this context, Living Arrangements (LAs) are identified as a basic determinant and an indicator of the care and nature of informal supports available to the older persons within the family, and therefore of their Quality of Life (QoL). In the current study, while understanding the family relations that are part of LAs of the older persons, the findings revealed who the hardest and easiest person to get along with them were, and that respondents’ perception about the level of interest shown by their family members towards their well-being varied according to their current LAs and seemed to impact their QoL and its related factors such as loneliness and adaptation to old age. The implications thereby point out to the necessity for efforts towards making families aware of who the older persons reported as having difficult relations with in the different LAs, what are the perceptions of older persons about indifference shown by their family members, and its possible impact on their lived realities. Further, planning appropriate interventions to improve the understanding and bonding between the generations, facilitating the family members to develop & practice positive attitudes towards the older parents/relatives and making efforts to spend quality time with them, are suggested actions for the social work practitioners. Key Words: Older Persons, Living Arrangements, Family Relations, Perceived level of interest and Quality of Life Introduction Ageing is a multi-faceted process that is determined not only by the passage of time, but also by certain physiological, psychological, social, economic, and cultural factors. Hence, the experience of ageing by individuals differs across the countries and regions. Moreover, there are variations in the experience of ageing even among the elderly within a country or region due to factors such as age, gender, marital status, health, place of residence, economic status, attitudes, work and retirement policies, importance given to social security, living arrangements, level of family support and the sexual orientation (Calasanti & Sleven, 2001; Virpi, 2008). In general, old age is seen both as a time of decline and fulfillment, depending on the individual and generational resources, and opportunities to which persons have access during their lives. Older persons are coming to comprise a significant proportion of a nation/country’s total population. The various demographic trends among the older population have been observed across the globe since the 1900’s. In 2013, the people aged (60 or over) comprised almost 841 million i.e. they were 12 % of the then total world population. It will increase more rapidly in the next four decades to reach % in 2050. During 2013, in the case of developing countries, the proportion of older persons ranges from 9% to 22% of their respective total populations (Global Ageing Watch Index Website, 2013). In India, the older persons (60 or over) comprised of about 121 million i.e. 9 % of the nation’s total population (Census 2011). For example, in India, 1 out of 5 persons will be found to be 60 or over years. Older persons are large in absolute numbers and this trend of their proportion in the total population will only increase in coming years. Along with demographic trends, rapid social change took place during the 1900’s due to the occurrence of the social processes such as industrialization, globalization, westernization and modernization. Changes in family structure (joint to nuclear), changes in family values & obligations, social roles, attitudes of individuals took place, women were going out to work, adult children migrated in search of better prospects. Individualization and lifestyle change, economic development, consumerism and technological advances occured. These sweeping changes altered the roles of older persons in the family and society, our attitudes towards them, ideas on obligations for caregiving and gave rise to social institutions that care for older persons. Hence, every issue may obviously effect a large number of older persons and therefore makes it necessary to identify them, understand their implications and attempt to address the same. In the Indian context, in keeping with the developments at the global level, and the Government of India being a signatory to the initiatives by the UN, a policy for the older persons and several interventions to enhance the quality of life of older persons were initiated. The Govt. announced the National Policy for Older Persons (NPOP) in January 1999. While recognizing the need for promoting productive ageing, the policy also emphasized the important role of family in providing vital non-formal social security for the elderly (Government of India (NPOP), 1999). In view of the changing trends in demographic, socio-economic, technological and other relevant spheres in the country, a committee was constituted for formulating a new draft National Policy for Senior Citizens (NPSC), 2011 that advocated priority to those needs of the senior citizens that impact the quality of life of those who are 80 years and above, elderly women, and the rural poor (Government of India (8th NCOP), 2010). The focus of the draft NPSC, 2011 would be to promote the concept of ‘ageing in place’ or ‘ageing in own home’. From this angle, housing and living arrangements, income security, home based care services, old age pension, access to healthcare insurance schemes and other programmes and services are seen as important to facilitate and sustain dignity in old age. This draft policy recognizes the need for intergenerational bonding, so that care of the senior citizens remains vested within the family, which may partner with the community, government and the private sector for provision of informal supports. Hence, it emphasizes institutional care as the last resort (Government of India (NPSC Draft), 2011). Family Relations One of the most influential factors in peoples’ lives is the environment in which they live. For the older persons this is particularly true as they spend most of the time in their home, as compared to other groups in the society (Van Solinge & Esveldt, 1991). Their living arrangements emerged as a parameter of great importance for understanding the actual living conditions of the older population in the developing countries (and their Quality of Life) within the contemporary ageing scenario, affected due to the lack of public institutions and social security nets (Sen & Noon, 2007). In view of this, exploring the above aspects has important implications for social work practice with the older persons- in improving their living conditions and quality of life within the rapidly changing contexts. Hence, in the current study, an attempt is made also to explore about the family relations within the living arrangements of the older persons (hardest and easiest person to get along with, frequency of arguments and tensions caused by hardest person, perceived level of interest shown by family members towards their wellbeing in different LAs as effecting their QoL domains and its related factors such as loneliness and adaptation to old age) that affect their quality of life. Method The data used in the present analyses were collected as part of an exploratory and descriptive study that was conducted during the period 2010-2012. A household survey of sample elderly respondents in the Vadodara (Urban) Municipal Corporation (VMC) limits was taken up using an interview schedule, as part of the quantitative approach and for qualitative approach the case study and observation methods were used. The schedule comprised of questions covering socio-demographic and family details, work and economic background, financial security, living arrangements, family relations, interaction with family members, social interaction, nutrition and access to food, leisure time and daily routine activities, preferential living arrangements and life preparatory measures. Measures like WHOQOL-BREF Questionnaire (WHOQOL Group, 1996), Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living (Katz, Down, & Cash, 1970), University of California and Los Angeles Loneliness scale (Version 3) (Russell, 1996), and Adaptation to Old age Questionnaire (Efklides, Kalaitzidou, & Chankin, 2003) were incorporated into the interview schedule to collect information about the key variables of the study. Both fixed end and open ended questions were used. Sampling Multi-stage probability sampling was used to arrive at a sample of 243 respondents who are 60 years and over, selected from the 13 wards in the Vadodara City. The map of the Vadodara city with the 13 wards already outlined was divided into equal sized grids and then the grids were serially numbered. Thus, it resulted in 26 grids. Out of the 26 grids, only 22 grids covered residential areas. Further, in the 26 areas which have been identified falling in the 22 grids covering the 13 wards, older persons living in the family context were enumerated using the preliminary data sheet. In this manner, a list with a total of 640 elderly was enumerated from all the 26 areas. Next, keeping the constraints of time and human power in view, it was decided to select randomly around 40 per cent of the older persons from the list thus generated. Thus, the researcher arrived at a sample of 250 respondents. While finalizing the filled interview schedules, 7 schedules were found to be incomplete and therefore were discarded thus making 243 persons as the final sample for study. The sample turned out to be purposive in view of the mobility and non-availability of some of the respondents when approached during data collection. Analytical Framework This article explored the family relations (an important factor of the living arrangements) such as the hardest and easiest persons to get along with vis-a-vis LAs, duration of stay and the frequency of tensions with hardest person and the perception of level of interest shown by others towards their well-being and its association with the QoL domains & its related variables. The hardest and easiest persons to get along with for the respondents’ could be associated with their sex, age and current living arrangements, and the respondents’ perception about the level of interest shown by the family members about their well-being may vary with the living arrangements. Further, it was explored whether these aspects might influence the Quality of Life and the related variables of the older persons. Results The data analysis of information pertaining to the family relations of older persons as part of their living arrangements collected during the study revealed various findings that are presented in this section. Profile of the Respondents Table 1 shows the distribution of the sample respondents by the kind of living arrangements that they currently dwell in and it was reported that a majority of them were living with their adult children who were married/unmarried (64%) followed by 24% who were living with their spouse only. The person hardest to get along with Of the 243 sample respondents, about half of them (comprising 58 men and 63 women) reported a family member as the hardest person to get along with in their life, who might or might not be living with them at the time of the study. Of the 121 respondents who reported a hardest person, about 55 per cent (n=66) said they were actually staying with that person. Of these, 80 per cent reported that person as their primary care giver. Now, who figured or were reported as being the hardest persons for the older persons? Son emerged as the hardest person in the case of both men (41 per cent) and women (32 per cent). Daughter-in-law (20 per cent) was the person hardest to live with for women (25 per cent) than men (14 per cent). The next hardest person reported was the spouse, mostly by the older men (21 per cent). While in the case of older men, the daughter or son-in-law did not emerge as the hardest persons to live with, in the case of a few older women they were reported as such. The other persons identified as hardest to live with were sister-in-law, siblings, grandchildren, nephew, niece, spouse’s relatives and children’s in-laws (see Table 2). It was further explored in Table 3 whether the age of the older persons was associated with who was the hardest person being reported. If we consider the median age of the elderly respondents, much older respondents (70 years) reported son and daughter-in-law as the hardest persons to live with. The respondents who mentioned spouse and daughter as hardest persons were relatively younger with their median ages being 68 and 66 years respectively. n=121 Note. a Include siblings, grandchild, nephew, niece, spouse’s relatives, and child (ren)’s in-laws. In the case of older persons who reported ‘others’, their median age was much lower (63 years) though the mean age was higher (66.8 years) indicating lot of differences in the ages of the respondents figuring in this group. On the whole, the relationship between age and the hardest person emerged as a pattern in the life course of respondents. Next, it was explored whether the relation named as the hardest person was associated with the living arrangements of the sample respondents. Of the older persons who lived in parent-child coresidence, a majority (43 per cent) reported son, followed by daughter-in-law (25 per cent) as hardest persons to live with. Further, in the case of those who lived with spouse, 27 per cent reported spouse as the hardest person to get along with. Thus, it appeared that parent-child coresidence, and living with spouse were the most frequent sites of conflict for the older persons (see Table 4). As indicated earlier, of the 121 elderly respondents who reported having a hardest person to get along with, more than 50 per cent (n=66) actually stayed with those persons and the duration of the stay is shown in Table 5. Though the overall duration of stay came to be 33 years, it varied greatly with reference to the relationship of the hardest person with the older persons. Thus, duration of stay of the respondent with the hardest persons- spouse, son, daughter and sister-in-law figured in that order. Though daughter-in-law figured among the hardest persons, the median duration of stay with her was short (15 years). Out of the 121 elderly who mentioned having a person hardest to get along with in their life, 86 reported that the hardest person caused arguments and tensions. According to the data, a majority (n=60) comprising of 73 per cent men and 67 per cent women reported that arguments & tensions with the hardest person occurred as frequently as about 10 times in a year. In the case of 23 per cent of the older persons (mostly women) such situations had occurred almost daily (see Table 6). Out of the total sample respondents, about 6.5 per cent (12 women and 4 men) reported abuse and neglect by family members in their current living arrangement. Not having a hardest person to get along with Out of the total sample, 122 older persons (52 per cent men and 49 per cent women) reported they did not have a hardest person to get along with in their life. Interestingly, they consisted of a majority of the older persons who belonged to the age range of 75-84 years (52 per cent), and more than half of the elderly who lived alone (56 per cent). Easiest person to get along with Next, the respondents were asked to mention the easiest person to get along with in their family. Out of the total sample, 239 elderly (50 per cent each of men and women) reported such a person in their life, who might or might not be staying with the respondent at the time of the study. The persons reported as easy to get along with varied with the type of living arrangements of the older persons. The details are as follows. Spouse (30 per cent), daughter (24 per cent) and son (22 per cent) figured in that order as the easiest persons to get along with. However, more men stated their spouse, and most women stated their daughter and son as the persons easiest to get along with. Slightly more men (7 per cent) as compared to women (4 per cent) mentioned that it was easy to get along with daughter-in-law (see Table 7). An attempt was made in Table 8 to see whether the relationship to the person mentioned as the easiest to get along was associated with living arrangements of the older persons. In case of the respondents who lived with the spouse, a majority 44 per cent followed by 33 per cent named the spouse and daughter respectively as the easiest person. Among the older persons living in parent-child coresidence, approximately equal percentage (30 per cent) of them reported spouse and son as the easiest to live with. Level of Interest shown by family members about the older persons’ well-being For the well-being of older persons it is not only important that family members show interest in them, but this has to be perceived as such by the older person. To look into this aspect, the respondents were asked to rate their perception regarding the level of interest of the family members about their well-being and the results are shown in Table 9. A majority (76 per cent) of the sample perceived that their family was interested in their well-being while around 13 per cent felt that they were somewhat interested in their well-being. A slightly more percent of women compared to men felt that their family was not interested or indifferent toward them. Data were analyzed to see the relationship between the type of living arrangement and the perception of the elderly sample about the level of interest shown by family members about their wellbeing. The results are shown in Table 10. It seems that a majority of the older persons across the five living arrangements felt their family was interested about their well-being. However, around half of the elderly who were living alone reported that their family members were somewhat or not interested about their well-being. Similarly 16.7 per cent and 5.5 per cent elderly living with relatives respectively felt that their families were somewhat interested and not interested. An attempt was made to examine the relationship between the different levels of interest shown by the family members about their well-being as perceived and reported by the elderly, and QoL domains, loneliness and adaptation to old age of the sample older persons, as shown in Table 11.

It could be seen that the older persons who perceived the family as interested in their well-being reported better on the 4 quality of life domains- physical health (14.74; SD=2.85); psychological well-being (16.14; SD=2.23); social relationships (14.30; SD=3.00); and, environment (16.93; SD=2.17). And they also experienced lower degree of loneliness (mean=43.19; SD=8.70) and have a better adaptation to old age (mean=63.74; SD=8.94). Interestingly, the older persons who perceived their family as indifferent to their well-being reported poorly on the 4 domains of quality of life experienced a higher degree of loneliness and had a poor adaptation to old age. This shows that there might exist a close association between the older persons’ perception of interest of the family about their well-being and their quality of life & related variables. The perceived indifference about their well-being by the family members was found to be more damaging for them. Major Findings and Discussion Hardest person to get along with 1. Of the 243 sample elderly, 50 per cent reported having a familymember who was hardest to get along with. 2. Son was mentioned most frequently (36 per cent) as the hardest person to get along with by elderly men (41 per cent) and women (31 per cent). The next hardest people reported were spouse and daughter-in-law. While none of the elderly men reported daughter or son-in-law as the hardest person to live with, in the case of elderly women they figured as the hardest persons. 3. For the elderly who lived in parent-child co residence, son (43 per cent) followed by daughter-in-law (25 per cent) figured as hardest persons to live with. 4. Of the 121 elderly who reported having a hardest person, about 55 per cent (n=66) reported they were actually staying with that person. Of the 66 elderly who actually stayed with the hardest person, 80 per cent reported that person as their primary care giver. 5. For the 66 elderly who lived with the hardest person, the overall duration of stay with that person was 33 years. Further, in terms of the duration of stay of the respondent with the hardest persons- spouse, son, daughter and sister-in-law figured in that order. 6. Of the 121 elderly who mentioned they had a hardest person, 71 per cent (n=86) reported that the person had been creating tensions and arguments, during the preceding year. Of these 86 elderly i.e., 70 per cent revealed that conflicts occurred 10 times a year, while 23 per cent of them said it occurred almost daily. 7. Out of the total sample, 122 elderly did not report having a hardest person to get along with. Interestingly, a majority (52 per cent) of the elderly who belonged to the age range of 75-84 years and more than half of the elderly (56 per cent) who lived alone did not report a hardest person to get along with. Easiest person to get along with 8. Out of the total sample elderly, 98 per cent (n=239) reported having persons in their life who were easy to get along with. 9. Of the 239 elderly who reported an easiest person to live with, a majority (30 per cent) reported the spouse as the one, followed by daughter and son. 10. In terms of living arrangements, 44 per cent of the elderly living with spouse reported that their spouse was the easiest person to get along with. Even in parent-child co residence, spouse was reported as the person easiest to get along with. Level of Interest shown by family members and the well-being of the older persons 11. A majority i.e. 76 per cent of the elderly perceived that their family members were interested in their well-being. 12. A majority of the elderly across all the five living arrangements felt their family was interested about their well-being. 13. Calculation of the means of quality of life scores and the related variables showed that the elderly who perceived their family as interested in their well-being reported better on the 4 domains of quality of life experienced a lower degree of loneliness and had a better adaptation to old age. Thus, the perceived indifference (than little or no interest) about their well-being by the family members was found to be more damaging for the elderly. With regard to the sample older respondents’ interaction with the children and family members in the context of different living arrangements, data indicated that nearly half of the sample respondents reported having a hardest person to get along with in the family and they are facing arguments and tensions created by such a family member. Most of the hardest persons reported are the primary care givers of the older persons. Interestingly, it appears that the most frequent sites of conflict for the older persons are parent-child co residence and living with spouse. Son followed by the daughter-in-law and spouse, have figured in these contexts as the hardest persons to get along with. Evidently, this is because a majority of the older persons live with their married son (s), and living with spouse is the next frequent form of living arrangement. This information clearly indicates that even while living in the family itself, the older person may be prone to instances of physical and emotional abuse. On the other hand, almost all the sample elderly (n=239) also reported having a family member who is easiest to get along with. This means that the older person who reported a hardest person almost always have a person with whom they had a trusting relationship, and who is a source of support for him/her in the living arrangement. Spouse followed by daughter and son are reported as the easiest persons to get along with. Even in parent-child co residence, spouse figured as the easiest person to get along with. The results further indicate that older persons who experience a positive environment in the family and who felt that their family is interested about their well-being, perform better on all domains of quality of life, experience a lower degree of loneliness, and have a better adaptation to old age. On the contrary, the perceived indifference of the family toward their well-being was found to be more damaging for the elderly. It may be noted that most of the elderly from the parent-child coresidence reported indifference of family members toward them. The reason may be that in this form of living arrangement the family members though living with them are often busy with their lives and have less time to spend or interact with the older persons. Suggestions and Implications for Social Work Practice Suggestions

Social Work Practice

References:

Dr. Smita Bammidi Assistant Professor, College of Social Work- Nirmala Niketan, Mumbai |

Categories

All

Social Work Learning Academy50,000 HR PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS. MHR LEARNING ACADEMYGet it on Google Play store

|

SITE MAP

SiteTRAININGJOB |

HR SERVICESOTHER SERVICESnIRATHANKA CITIZENS CONNECT |

NIRATHANKAPOSHOUR OTHER WEBSITESSubscribe |

MHR LEARNING ACADEMY

50,000 HR AND SOCIAL WORK PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed