|

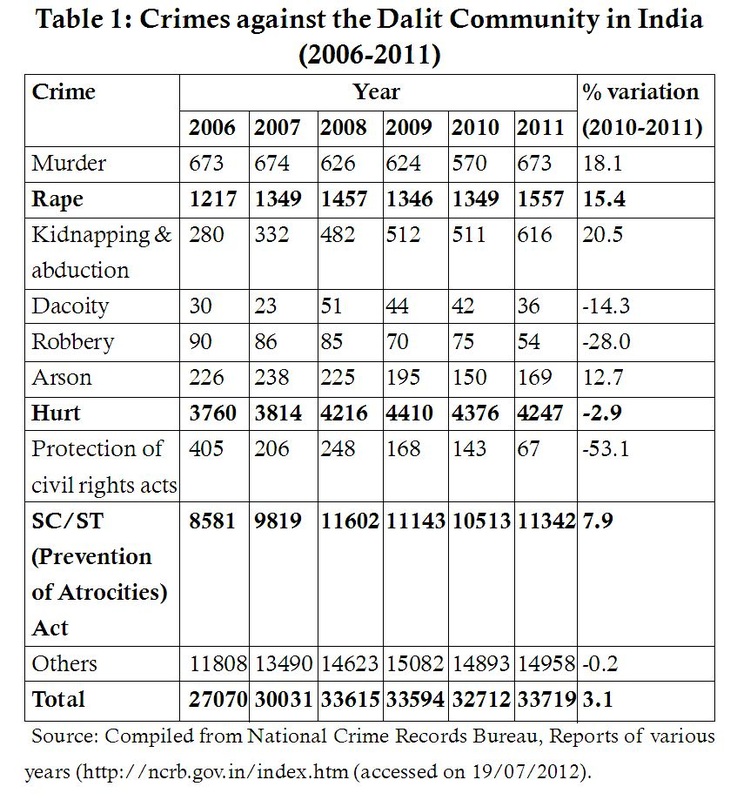

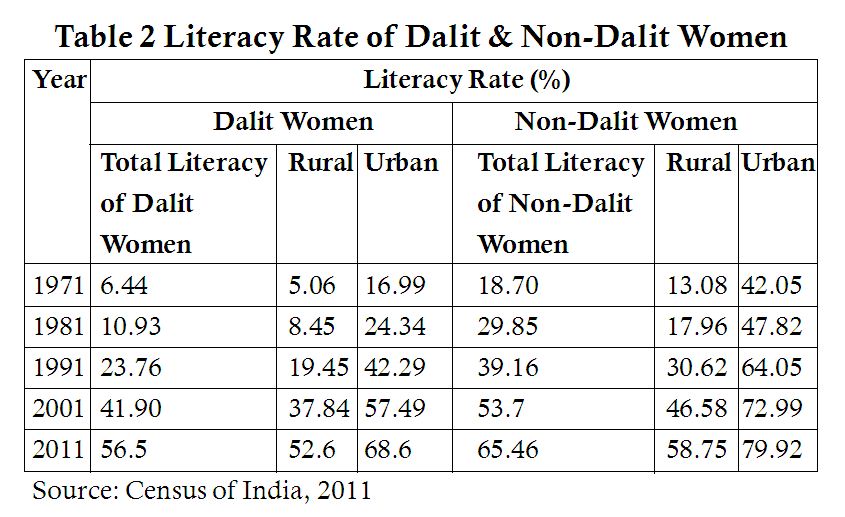

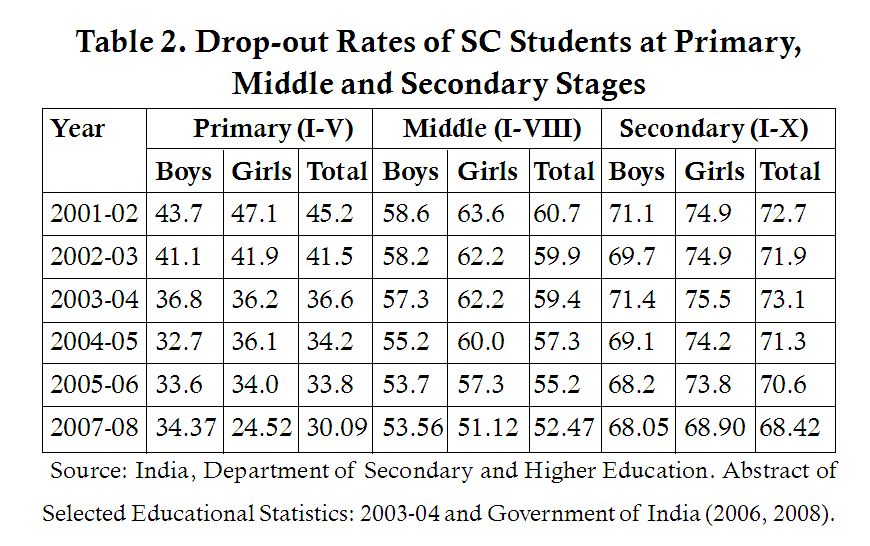

Abstract Dalit women constitute a vast section of India’s population; they have been socially excluded and humiliated for a long period of time. Dalit women are compelled to live a vulnerable life, be it economic, education, health and all other areas that fall under basic needs. They are denied justice, equity as well as social and political participation. Impoverishment and marginalization of the vulnerable Dalit women have been going on unabated since long time. In recognition of the unique problems of the Dalit women the Indian Government through ‘Positive interventions’, ‘affirmative measures’ have consistently developed policies for their economic, social and political empowerment. Though these policies have brought some positive change, however, the process of transformation has been extremely slow. The policies are inadequate to minimize the handicaps and disabilities of the past and in reducing the gaps between them and the rest of the Indian society. Dalit women continue to suffer from a high degree of poverty, gender discrimination, caste discrimination and socio-economic deprivation. In this context, the paper addresses the issues of education, health, employment, poverty, inequality and exclusion of Dalits in general and Dalit women in particular in the contemporary Indian society. The focus of the paper is to understand the various policies and perspective in planning best remedies and measures to eradicate the social discrimination and ensure equity participation of Dalit women in every spheres of life. It also identifies the challenges that confront their main streaming emancipation and empowerment in contemporary times. Key Words: Dalit Women, Empowerment, Discrimination, Exclusion Education. Introduction India celebrated the seventy years of independence and since long time Dalit women issues are not reflected in either Dalit intellectual discourse or non-Dalit women discourse. After independence, Govt. of India through five-year plans formulated various policies and programmes for women empowerment in general and Dalit women (SCs) in particular. Constitution has provided safeguards for Dalit women’s development vis-à-vis empowerment. According to the 2011 Census, 201 million people belong to the Scheduled Castes (Dalits), which constitute 16.2 per cent, of the total population of the country (Census 2011). In India, Dalit women constitute 49.96 per cent of the total Dalit population, 16.30 per cent of the total Indian female population (Ruth, Manorama, 2000). Though Dalits are found in almost all the states, they are largely concentrated in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar in the north, West Bengal in the east, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh in the south, Rajasthan, Gujarat and Maharashtra in the west. The vast majorities i.e. 84 per cent of the Dalits (SCs) live in the rural area. Sociologically speaking, Dalits are the most deprived sections of the Indian society in general and Dalit women in particular. They suffer from the stigma of untouchability and various types of atrocities or violence inflicted on them by the non-Dalits. Dalit women are triple exploited in the Indian society, first by class, second in terms of caste, third of gender and they have marginalized status in the caste-hierarchy of our society (Ghansham Sha, 2000). Since the dawn of Indian independence, several efforts have been made to provide socio-economic, educational, political, and employment opportunities to this most neglected segment of the society. It is indeed to note that after seventy years of our independence and sixty six years of planned era the development-vis-à-vis empowerment of Dalit women remains far from the unsatisfactory and India representative democracy and the country’s declaration of being a “Welfare State” the pathetic conditions of the Dalit women do not permit us to say that all the policies and programmes have achieved their targeted goals. Social Status of Dalit Women Inequalities of Dalit women in indian social structure are the most grave and inadmissible as it has a direct impact on their status. The inequity is systematic, produced by social norms, policies and practices that promote unfair distribution of power, wealth and other necessary social resources. According to Whitehead et.al, 2007 inequities arise due to social hierarchies inbuilt in social system. The status of Dalit women depends on the socio-economic and political factors which in turn affects their lives and not merely on the presence or absence of any programme and policies. Caste and social stratification in India determine health, education, employment, social, and economic outcomes (Jacob, 2009). The discrimination faced by Dalit women at the cost of the Brahmanical obsession with “purity and pollution” has had a detrimental effect on all the dimensions of development. Since evolution of human being Dalit women face various forms of exclusion and discrimination in Indian society. Even today Dalit women along with their families are commonly clustered in segregated hamlets at the edge of a village or mohallas in one corner of the village, devoid of civic amenities: drinking water, health care, education, approach roads etc. In urban areas their homesteads are largely found in slum bastis normally located in very unhygienic surrounding. They are most vulnerable groups, who are easily subjected to exploitation and violence. Their life is most unprotected and insecure in Indian society, owing to the secondary role and patriarchal and hierarchal structure of Indian society, 90 per cent of them are facing several problems; they suffered violence to a greater degree than men. The exploitation of them under the name of religious such as “Nude Worship,” practice of devdasi system and such other similar types of practices make them more submissive to violence, and discrimination (Encyclopedia of Dalit in India, 2002). Majority of them are working as agricultural labourers. Thus there is both diachronic and synchronic relationship between the social disadvantages and empowerment of the Dalits women. They are mostly engaged in “civic sanitation work” (i.e., manual scavenging, even though this has been outlawed). The manual scavengers are mostly Dalit women whose duty is to clear human excrement from dry pit latrines. Those who are engaged in scavenging are seen as the lowest of the dalits, being discriminated (Human Rights Watch, 2009). These occupations are not only characterized by their precariousness and substandard working conditions, but also are usually excluded from labour protection laws and policies. Dalit women who are not forced into degrading occupations are discriminated against by means of lower wages, longer periods of unemployment and fewer opportunities for work. They have more difficulty getting hired by others because business owners normally prefer to hire those from their own caste. The risky workplaces compounded with a lack of labour rights protection measures render migrants dalit women more vulnerable to occupational injury. Further, the emerging problem of sub-contracting short-termed labour makes it more difficult for them to claim compensation when they are injured at work places. The employer’s responsibility for workplace injury compensation is being transferred to the broker who sub-contracted the worker. Dalit women are most vulnerable to abuse and exploitation by employers, migration agents, corrupt bureaucrats and criminal gangs. In many situations, dalit women do not know what rights they are entitled to and how to claim them; hence the cases of abuse go unrecorded. Every year, millions of poor dalit families migrate in search of work. They are forced to migrate due to a livelihoods collapse in the villages. Among the migrants dalit women are the most vulnerable. They face a huge challenges and distress due to seasonal migration. At worksites, migrant dalit women are inevitably put to work for long hours. Semi-skilled, low-skilled or unskilled women migrants, are put into the low paying, unorganized sector with high exposure to exploitation. The enslavement trafficking also contributes to migration of large proportion of dalit women. Dalit female migrants face hazards that testify to the lack of adequate rights protection and opportunities to migrate safely and legal provision. Their social disadvantages have ever since manifested in the forms of practice of untouchability, including discriminations, and atrocities committed against them both in public and private spheres. Though the practice of untouchability and social discrimination have legally been abolished, yet it continues to be high magnitude. Table 1 presents the various type of violence against dalits in India between 2006 and 2011. Economic Status of Dalit Women The Government implemented the “reservations” policy to create job opportunities for dalits. However, the reservation system has only minimally benefited the dalit women. This is partly because the system applies only to the government sector. Moreover, the system is reported to be flawed because many jobs are left unfilled and because of a lack of commitment on the part of a government dominated by upper caste politicians. Most of the reservations are in low skill, low paying jobs. The 2001 census figures show that over half of the dalit workforces were landless agricultural laborers, compared to 26 per cent of the non-dalit workforce. Among those who own land, a vast majority, i.e, nearly 86 per cent are small and marginal farmers. In 2011 census, out of 13.29 million dalit women main workers, 8.83 millions were reported as agricultural labourers and 2.33 million as cultivators. 3.93 million dalits women were also reported as marginal workers (Census, 2011). The National Sample Survey (NSS, 2014) data on employment for 200 indicates that more than 60 per cent of the dalits workers lived in the rural areas and were-dependent on the wage employment. In 2006, the Current Daily Status (CDS) of employment rate in the rural areas was 21.2 per cent for the dalits female workers, compared with 46.2 per cent for dalit male workers (NSS,2014). Similarly, the CDS employment rate for dalits female workers in urban areas was 14.0 per cent, compared to 45.8 per cent for other households. In 2004-2005, 43.7 per cent dalit women were self employed, 5 per cent were regular wage salaried employees and 52 per cent were casual labour. In 2009-2010, 35.9 per cent dalit women were self employed, 6.5 per cent were regular wage salaried employees and 57.6 per cent were casual labour (GOI, NSSO, Employment and Unemployment Situation in India: July 2009- June 2010). Disparities between dalit women and non-dalit women’s are reflected in the unemployment rate. Unemployment rate based on CDS for Dalit women was about 2.10 per cent; compared to about 1.40 per cent for other non-dalit women workers in rural and urban areas. With high ratio of wage-labour associated with high rate of under-employment and low-wage earnings, the dalit households suffer from the low income and high level or degree of poverty. This also reflects in the proportion of persons falling below the poverty line, and what is also called a critical minimum level of consumption expenditure. The dalit women households were over-represented in these groups. The high level of poverty among those dalit households engaged in self-employment in agricultural and in non-agricultural activities indicates that they were normally concentrated in the small farming and the low-income petty businesses particularly dalit women (Dubey, Amaresh, 2003). Since the nineteen seventies, the state has launched a number of poverty eradication programmes but the dalits women have not been benefited. Various land reforms such as those related to ceiling and distribution of surplus land have somewhat enhanced dalits access to land, but these measures are also not sufficient to dalit women. Rather, these have led to the various kinds of tension and conflict between the dalits and non-dalits, and consequent atrocities inflicted on the former by the latter in the rural areas. Their economic situation has worsened due to the overall deteriorating rural economic conditions over the last two decades as a result of the New Economic Policy. Moreover, entrepreneurial opportunities are extremely limited for migrant dalit women as they lack both capital and the collateral to secure loans. Even if dalits are successful in opening small businesses, non dalits do not patronize those shops (Artis et al., 2003). They also face problems of social integration in cities. There are reports of large number of human rights violations. Another area where exploitation is rampant is forced labour which takes place in the illicit underground economy and hence tends to escape national statistics. They face higher risks of exposure to unsafe working conditions. This population is at high risk for diseases and faces reduced access to health services. The rapid change of residence due to the casual nature of work excludes them from the preventive care and their working conditions in the informal work arrangements in the city debars them from access to adequate curative care. Educational Status of Dalit Girls Education is an important input for human resources development and it plays a key role in empowering women in general and dalit women in particular. It is a very powerful instrument for emancipation of dalit women. It not only improves prospects for economic development but also promotes self-confidence and helps in capacity building to meet the challenges that the changing socio-economic scenario poses. But, the historical experiences of dalit communities particularly in the context of education were based on deprivation and oppression. They were traditionally denied access to learning due to their so-called polluted and lowest status in the Indian caste system. After independence, Govt. of India has made several protective measures through the constitution safeguard for the Human Rights of Dalits. The abolition of untouchability (Article 17), Prohibition of ‘beggar’ or ‘forced labour’ (Article 23), ‘positive discrimination,’ reservation in appointments of Governments services and post (Article 335) are some of the examples. Similarly, there is a clear provision in the (Article 46) of the Directive Principal of State Policy which provides that “The State shall promote with special care the educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the people in particular, of the Scheduled Castes and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation”. To fulfil these Constitutional Directives, efforts have been made by the Government to improve educational standards of dalits by extending educational facilities by providing scholarship, stipends, textbooks, stationary, uniforms, mid-day meals and hostel facilities. Though it is a fact that literacy rates among dalits women have shown improvement, the decadal rate of growth in literacy is very slow as compared to the literacy rate of the non-dalit women. In 2001, the literacy rate of dalit girls was particularly low (42 per cent) less as compared to non-dalit girls. Although the literacy rate among dalit girls has gradually increased over the past 68 years of independence, the decadal rate of growth in literacy is very slow as compared to the literacy rate of non-dalit girls. The literacy gap between them and non-dalit girls continue to widen and disparities continue to be pronounced between them (Table 2). However, they are lagging far behind in the field of education and have the lowest literacy levels amongst all groups in India. Besides, there are some dalit communities, which do not have any literate women among them. Even after 68 years of independence, most of the dalit girls of school-going age do not get enrolled in schools and those who get enrolled do not pursue studies for more than two to three years. Every second enrolled girl child from the dalit families drops-out before completing primary education (up to Vth standard). Over the last two decades, the Government has increased elementary school provision (grades I-VIII) throughout the country and this has marginally increased the rates of enrolment. But the dropout rates of dalit girls are considerably very high as compared to non-dalit girls and dalit boys in primary, middle and secondary stages. In 2004-2005, the drop-out rate for dalit girls was 60 per cent (compared to 55 per cent for SC boys) at the elementary level. There are various reasons for drop-out of dalit girls (Table 3). The education of dalit girls is a serious issue as they are often doubly disadvantaged, due to both their social status and their gender. Gender equity is a major concern, as the drop-out rate is higher among them at the elementary level. Dalit girls are particularly disadvantaged because family and social roles often do not prioritise their education (Bandyopadhyay and Subrahmanian, 2008). Early marriage and poverty leads to large scale drop-out in the 5-10 year old and 16-20 year old age groups, interrupting the completion of girls education (Naidu, 1999). However, this is not the only reason that dalit girl drop-out. Memories of humiliation can also play an important role in the decision to leave, albeit a less visible one (National Commission on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, 1998). There is also a feeling that reservation of seats and preferential treatment benefit dalit students, but empirical reality is quite different. It has been seen in various studies that there is minimum enrolment of dalit girls. However, issues of quality and relevance of schooling for dalit children have barely received any attention from the national Government. The poor quality of infrastructure, teaching and a curriculum that does not relate to the socio-cultural lives of the dalits nor teach about their history, have all contributed to the communities’ disenchantment with schooling. Apart from this, ninety-nine per cent of dalit girls study in government schools that lack basic infrastructure like classrooms, teachers and teaching aid. Dilapidated buildings, leaking roofs and mud floors appear quite common in such schools and provide a depressing atmosphere for children. All these aspect are effects accessibility of school among dalit children. In contrast, it is common for non-dalit children to seek private tuitions or to access private education of better quality. The motivation to do so comes from the fact that most primary government schools are considered to be of low quality. The dalits being economically poor are unable to access such supplementation to their education; this further increases the education gap. The issues of self-worth, dignity and livelihoods that school education has failed to address or even acknowledge also arise for dalits. Once enrolled, discrimination continues to obstruct the access of Dalit girl children to schooling as well as to affect the quality of education they receive. From the above figures, it is clear that the dropout rates of SC girls students is considerably very high as compared to SC boys. The basic data and educational profile of dalit women mentioned above clearly indicates a very alarming situation in spite of all the constitutional provisions and efforts put in the field of education. It is indeed to note that even after sixty five years of our Independence and Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the empowerment of dalits in general and a dalit girls in particular, the field of education remains unsatisfactory. The various schemes and policies have failed in accelerating and retaining the dalit girls in education sector. Even today, the vast majority of dalit girls ‘drop-out’ from school well before they complete eight years of education. The enrolment status of dalit girl children is lower than that of boys and this difference goes on increasing as we move towards higher level. It highlights the extent of social exclusion despite enforcement of various education policies by the State and Right to Education Act, 2009. It deals to what extent and in what ways do the oppressive and unjust hierarchies of the caste system continue to ‘lock’ dalit girl children out of full participation in education within schools. It emphasizes the need to promote Education of Dalit Girls in the form of content and quality of schooling, teachers, materials, enrolments, retentions, acquisition of basic literacy and numeric skills.

In higher education, the status of dalit women is poor as compared to non-dalit women. According to a study, out of hundred, only 12-14 dalit students reach up to matriculation and dalit women reaching matriculation are very poor in number when compared to the dalit men. Studies have also shown that the representation of dalit women in higher education is lower than their proportionate representation of the population, which is attributed to their poor socio-economic background. So, the issue of enrolment, sustainance and performance in higher education need a fresh look when one talks of equality of educational opportunity. In the context of providing educational opportunities with special incentives like free-ship, scholarship, hostel and reserved seats, the issue of enrolment is crucial. Inequality of educational opportunities, however, cannot be removed through simple enrolment. What actually tackles the issue of inequality in education is acquisition of knowledge or academic achievement (Aikara, 1996). Owing to the poor economic conditions, dalits cannot afford to send their children to big institutes like Jawaharlal Nehru University, Birla Institute of Technology, Pilani, Indian Institute of Technologies, Indian Institute of Managements. Most of these schools are located in the cities and urban centres. On the other hand, eighty percent of the dalits live in villages, making it practically impossible for them to benefit from these institutions. Besides, illiterate and undereducated dalit parents are unable to introduce their children to the culture of the elite, which is generally represented by the elite educational system. The dalit parents neither have a paying capacity nor they have any provisions to send their children to such schools and therefore they are forced to send their children to village schools where teaching staff and the infrastructure are generally in poor conditions. That is why even those who aspire for higher education are often compelled to join liberal B.A, B.Sc and B.Com programmes. The basic data and educational profile of dalit women mentioned above reveals that in-spite of all the constitutional provisions and efforts put in the successive plan periods, it appears that dalit women have still to go a long way to come up to the general level in the field of education. The poverty, non-attendance in school, high dropouts in school, poor quality of education, discrimination in education are some of the educational problems faced by dalit women both in rural areas and slums in the cities. Their low level of literacy is due to three interrelated factors: (a) continued monopolization of state, economic, cultural and other resources by middle and upper class groups; (b) the stronger influence of casteism in rural areas on dalit females; and (c) the control of dalit males over dalit women and girls. As a consequence, dalit females’ access to even basic literacy education is limited. Water and fuel scarcity have a direct influence on Dalit girl’s access to education. Poverty compels most rural dalit parents to send their children to work rather than to school. Many dalit parents view education for girls as a luxury, pointing out that it is expensive and there is a lack of gainful employment opportunities after graduation. However, many parents also feel that education beyond the primary level for girls will affect their household management. Dropout and non-enrollment is also due to several other factors, including the lack of childcare facilities in villages; cooking, cleaning and other domestic chores; employment as child labourers to help support the family, education and marriage of siblings; and the attitudes of parents and the dalit community. Health Status of Dalit Women Unlike any other sections of the society, dalit women are less likely to benefit from the meager health care benefits provided by the Government due to social exclusion and discrimination. The year 2007 marked a mid-way to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) 2000-2015 and the fourth year the government brought to power on its promise to meet and exceed the MDGs through the full implementation of the National Common Minimum Programme (NCMP) of United Progressive Alliance (UPA). Yet, despite the growth in the ‘Other India’ millions of dalits remain excluded from the most basic rights and are subjected to the tyranny of mass hunger, illiteracy and ill-health. Issues of sustainable livelihood and health of these groups exists as the major problem. The statistical information about health status of dalit women is quite alarming. The empirical evidence (NFHS-2, 1998-1999) indicates that dalit women suffer from exclusion and discrimination in terms of education, access to health services and level of nutritional status. The disaggregated data based on social groups highlight the extent of disparities prevalent among dalit women in India with particular emphasis on access to health services (NFHS-2, 1998-1999). There are growing inequities in mortality and nutrition at all India level, across states, as well as within states and social groups (Deaton and Dreze, 2009). Their studies show persistence of inequities and worsening of health outcomes for vulnerable groups such as SC and women, especially those belonging to the lower caste. The data of maternal and child mortality may vary from state to state but mortality is high among dalit women as compared to non-dalit women across the states. However the differences are more in poor performing states like UP, Bihar, Chhattisgarh or Jharkhand. Unfortunately these are also the states with substantial population of SC (Nayar, 2007). The situation of dalit women is of great concern due to their multiple identities. Gender discrimination has an enormous multiplying effect on their health. They are subjected to sexual violence, denial of education and work opportunities and discrimination in social and civic life all of which lead to impaired health status. The child marriage, child labour, devadasi system, prostitution as a consequence of trafficking are the endless problems that dalit women face. As a result the health condition of dalit women is affected leading to high incidences of maternal mortality. This is also due to the fact that dalit women are unable to access health care services. The denial and sub standard healthcare services leads to life expectancy of dalit women as low as 50 years. Due to poverty, they are malnourished and anaemic. Because of lack of awareness and medical care, many of them suffer from reproductive health complications, like cervical cancer. They face forced sterilization, are tested for the use of new invasive hormonal contraception like guinea pigs. They are forced to use long-acting, hormonally dangerous contraceptives. Maternal health care is free in India, but dalit women receive less prenatal care (NCDHR, 2006). Unfortunately, dalit women in some states, such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Rajasthan, do not get adequate prenatal care (NCDHR, 2006). Data from Kerala suggests that even in a state with good health outcomes, 88 per cent of SC women had reported of having poor health which is higher compared to higher caste women (Mohindra et. al, 2006). Another more important aspect is health status of the dalit women are associated with degraded working environment, mental stress, long hours of work, lifting of heavy weights, contact with hazardous and infected material, inconvenient postural conditions of work etc. Besides occupational hazards, they suffer from malnutrition, anaemia, post-delivery complications, tuberculosis, chronic eye problems and general debility due to low level of food intake, child bearing and constant enforced deprivations. In 1998-99, at least 56 per cent of the SC women had suffered from anaemia. More than 70 per cent deliveries took place at home and only one-fifth took place in health care institutions. More than 40 per cent of these deliveries were conducted by TBAs (Village Dais). The extent of malnutrition and under-nutrition among the dalits children is also very high, as more than half of them suffered from this problem. The infant mortality rate is 83 per thousand and the child mortality rate is 39 per cent among the dalits. Even the incidence of morbidity among their children is very high. For instance, more than three-fourth of the dalits children are anaemic, one-fifth to one-third suffer from fever and another one-fourth from the anaemic infant rate (AIR) and diarrhea. The high morbidity and child mortality among them is closely linked with poverty. The low educational status, discriminatory access to health services, and high rate of illiteracy and poverty reduce the overall capacity of the dalits to demand and utilize the public health services, (National Family Health Survey, 1998-99). Thus, in terms of every index of social empowerment such as social, education, health, employment, and poverty etc., the dalits women lag behind the non-dalit women. Affirmative Action Policies and Status of Dalit Women Even after 60 years of various affirmative action policies and programs, there remains very little improvement in the socio-economic status of dalit women. The main reasons include (1) Corruption at all levels and poor receive less than 10 per cent of actual funds for development programme (2) there are caste, gender, class, urban and age bias in policies and programs (3) The fact of dalit women’s experiences and multiple oppressions being different from other groups. Due to caste and gender related privileges, dalit men from a few SC sub-caste groups are chief beneficiaries of affirmative action programs for SCs. Dalit women have limited access to caste benefits-as do the most disadvantaged caste groups, due to class stratification among dalit sub-groups. Affirmative action programmes for the poor and other class-based benefits go mainly to men from a few urban, sub-class groups. Rural dalit females, as members of the most class disadvantaged group, are the one who receive the least in terms of these class-based programs. Urban-based male dalit children are the primary beneficiaries of programs for disadvantaged children. Although there are more urban dalit females working as child labourers, like rural dalit girls, they remain invisible. Affirmative action programs for women are dominated by upper caste Hindu and biased towards their gender, religious, and cultural issues. In terms of other religious-based programs, like Christian, Sikh, and so on, each is bias to help dalits who may be converted to their religion. The majority of rural, Hindu-Dalit females are seldom benefited. Untouchability continues because past discrimination continues in more subtle ways into the present; the rapid economic deterioration among the rural poor caused by the effects of the New Economic Policy (NEP) and the increasingly repressive forms of caste and gender oppression on dalit females; the continued economic bias of discrimination by middle class/caste control over low class dalit women, etc., including dalit females’ economic exploitation of being paid even the starvation level minimum wage, absence of land reforms; and so on; the existence of an ideological basis for discrimination as the root cause of the problem-legitimized by male Brahmanical structures and so on, and finally and the silencing of dalit voices in cultural, political, historical, spiritual spheres. As a result of all of the above, the participation of dalit women in organized sectors is considerably low or negligible. Conclusion There are various factors responsible for dalit women backwardness like poverty, illiteracy, home environment, apathetic attitudes towards education, lack of family support, gender discrimination, caste violence, etc. But despite these factors, the socio-economic, educational progress of dalit women is a little more than before. There are three main reasons of failure in affirmative policies The first main point is that the experiences of poor, rural dalit females are different from those of other poor and rural groups, from other Indian women, and from dalit males. Consequently, the vast majority of affirmative action policies and programs, which are targeted towards the rural areas, the poor, women or dalits, do not necessarily reach perhaps the most disadvantaged group i.e., poor, rural dalit females. The second main point is that dalit females suffer from the interconnections of multiple oppressions of class, caste, gender, and cultural at all levels (household, village, district, state, national and global) by both men and women, from all castes and classes. The third point is really a consequence of the first two points, i.e., that affirmative action programmes and policies should be designed specifically to improve the status of rural dalit females, and that such policies and programmes need to take into account the specific nature of the interconnections of gender, caste and class oppressions at all levels, along with the need to incorporate dalit women and girls themselves into decision-making and leadership. The processes of globalization, market economy and state-sponsored privatization of development have added to the further marginalization of the marginalized ones over the last decades. In addition, globalization is creating its impact on the community and the identity dimensions of the people particularly dalits in India. The pattern of the impacts of globalization has been shaped by the social and economic inequalities. The excluded ones in the Indian society, i.e., the poor and the dalits, are going to be further marginalized in terms of all these processes due to shrinking of the public sector through the disinvestments of the public assets and resources which have hitherto been the major sources of social mobility for dalit women. Therefore it is important for the Government to introduce welfare measure and create healthy atmosphere for dalit women . References

|

Categories

All

Social Work Learning Academy50,000 HR PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS. MHR LEARNING ACADEMYGet it on Google Play store

|

SITE MAP

SiteTRAININGJOB |

HR SERVICESOTHER SERVICESnIRATHANKA CITIZENS CONNECT |

NIRATHANKAPOSHOUR OTHER WEBSITESSubscribe |

MHR LEARNING ACADEMY

50,000 HR AND SOCIAL WORK PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed