|

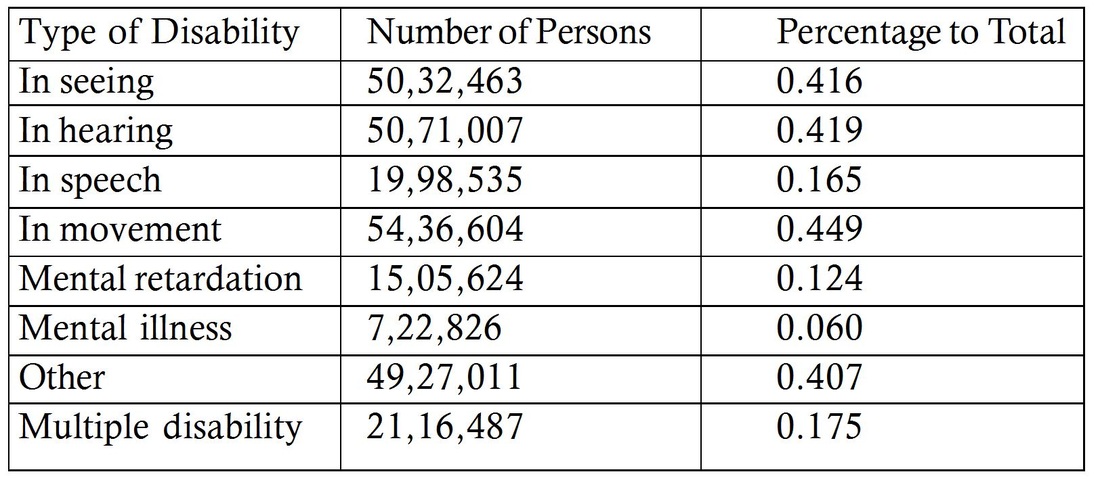

Abstract Disability has always been looked down upon by the society and the differently abled persons have not yet been included in the mainstream society in many countries in the world. The article analyses the various models of disability and advocates for the adoption of the social model of disability along with rights based advocacy and activism. India is far behind the developed nations in creating an inclusive society because of the continuing barriers at different levels despite laws and policy pronouncements. Concept Differential ability is the norm in all societies. Ability is a continuum and absolute ability is a rarity. But due to false beliefs and prejudices, disability to perform the various personal functions and activities independently has been looked down upon by the so-called “normal” persons, and persons with disabilities (PWDs) are marginalized and socially excluded. The World Health Organization (1996) defines disability as “any restriction or lack of ability to perform an activity in a manner or within a range considered normal for a human being.” The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006), in Article 1, defines PWDs as “those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others”. The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2014, defines a person with disability as a person with long term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairment which hinders his/her full and effective participation in society equally with others. Disability is defined to include 19 conditions. The Act defines barrier as any factor including communicational, cultural, economic, environmental, institutional, political, social or structural factor which hampers the full and effective participation of persons with disabilities in society, The Act also defines persons with Benchmark Disability as persons with not less than 40 per cent of a specified disability. Models of Disability It is only during the last part of the twentieth century that the term “disability” has been used to refer to a distinct class of people. There are many models put forth on disability by people who claim to be. concerned with the phenomenon. The prominent two models are the Medical Model and the Social Model. The Medical Model of Disability This model explains disability as a physical or mental impairment of the individual. It views disability as a problem of the person, caused by disease, trauma or other health condition which requires sustained medical care provided by professionals. The Medical Model is also known as the Biological-Inferiority or Functional Limitation Model (mymdrc).Medical practitioners are those who devised this model. The Expert or Professional Model is an offshoot of the medical model. This model produces a system in which an authoritarian professional service provider prescribes and acts for a passive client (Langtree). The Social Model of Disability This model explains disability as a socially created problem and a matter involving the full integration of individuals into society. According to this model, disability is not an attribute of the individual, but a complex combination of conditions, most of which are the creation of the social environment (Langtree). The social model views impairment as normal for any population. What disables people with impairments is a web of discrimination made up of negative social attitudes and cultural assumptions as well as environmental barriers, policies, laws, structures and services which cause social exclusion and economic marginalization (Albert & Hurst, 2005). The social model of disability “gives us the words to describe our inequality. It separates out disabling barriers from impairment...........” Because of this, the social model “enables us to focus on exactly what it is which denies us our human and civil rights and what action needs to be taken” (Morris, 1991). The philosophy of the social model originated in the Civil Rights Movement in the US. Hence it is also referred to as the Minority -Group Model of disability. It argues that disability stems from the failure of society to adjust to meet the needs and aspirations of a disabled minority. It is similar to the doctrine of racial equality which states that “racism is a problem of whites from which blacks suffer”. This model places the onus upon society and not on the individual (mymdrc). Disability and the attendant low social, economic and political status is no way a result of divine proclamation, but a direct consequence of social attitudes, myths and misconceptions proffered by the able-bodied majority (Drake, 1999). Fischer (2006) refers to this as “apartheid by design”. Equal access for a person with an impairment or disability is a human rights issue of major concern. (Langtree). The exclusion of persons with disability is manifested not only in deliberate segregation, but in a built environment and organized social activity that preclude or restrict the participation of people seen or labelled as braving disabilities. Social philosophers began to see disability as a source both of discrimination and oppression, and of group identity, akin to race or sex in these respects (plato. stanford). The Moral Model The model is of the view that individuals are morally responsible for their own disability. In congenital instances disability is seen as a result of the bad actions of the parents. This is a religious fundamentalist explanation (Langtree). The Hindu doctrine of Karma attributes the disability or suffering of an individual to his or her bad deeds in the previous birth or the evil deeds of the parents. The Tragedy or Charity Model This model views persons with disabilities as victims of circumstances and hence they deserve others’ pity. This and the medical models are the most widely used by the non-disabled persons to explain disability (Langtree). Charitable bodies and fund-raising, donor organizations exploit this negative victim-image to raise huge funds from society. Donnellan (1982) described the fund raising appeals through television channels as “televisual garbage” which was “oppressive to disabled people”. Many international donor agencies are criticized for raising humongous amount of funds and spending on the lavish life style of the donor administrators at the cost of the money raised in the name of children and adults with disability. The Rights-based Model of Disability This model has arisen in recent times which conceptualizes disability as a socio-political construct. As there is a shift in emphasis from dependence to independence, persons with disability have been seeking a political voice and have become politically active against social forces of “ableism”. Disability activists are projecting identity politics and have been adopting the strategies used by different social movements for human and civil rights against issues as sexism and racism (mymdrc). Disability movement across the world has been complaining that the perspectives of people with disabilities are most often ignored and discounted in policy making and programme implementation. The title of James Charlton’s book (1998) “Nothing about Us without Us” has its source the slogan of the disability movement. Social Exclusion Stewart, et al (2006) explain social exclusion as a concept “used to describe a group or groups of people who are excluded from the normal activities of their society in multiple ways.” The European Union states social exclusion “as a process through which individuals or groups are wholly or partially excluded from full participation in the society in which they live” (Laderchi ,et al, 2003). Social exclusion, for the Council of Europe, is a broader concept than poverty, and it encompasses not only low material means but also the inability to participate effectively in economic, social, political and cultural life, and even alienation and distance from mainstream society (Duffy, 1995). Disability is the result of those actions of the non-impaired majority in society that inhibit the lives of people with impairment (Drake, 1999). Disability or diabolism joins racism, sexism, and homophobia as a form of social oppression (Thomas, 2003). Persons with Disabilities in India The Census of India estimated 26.8 million persons with disabilities in the country in 2011 out of the total population of 121 billion. They constituted 2.21 percent of the total population. The types of disabilities and their frequencies in the country were as follows (punarbhavain): These statistical data is definitely an underestimate. A large number of persons with disabilities are not properly enumerated by the persons retained for census enumeration. Social worker and researcher, Professor T.K.Nair narrates his experience during the 2011 census enumeration. During the two rounds of enumeration he repeatedly asked the enumerator whether he would need the data on disability for which he mentioned that there was no provision in the census forms. On further enquiry, he admitted that he was doing the work on behalf of the real enumerator, a female relative.

Indian Society and Disability Indian society has never been an inclusive society. The dominant, higher castes excluded the lower castes; the rich always exploited the non-rich and the poor; the non-disabled always marginalized the persons with disability. Hindu scriptures enjoin upon the followers to believe in the Karma (deeds) of the previous births of the individuals or the parents. Other religions also explain poverty, serious illness and disability with past sinful deeds in some form or the other. Persons with disability are referred to by the disability and addressed contemptuously. Hindi and languages with Sanskritic origin classify the persons with disability as “Vikalang” while other regional languages use the variants of this distasteful categorization. While in English, there has been progressive changes in referring to the persons with disability from “handicapped” to physically or mentally challenged as well as to differently abled, the Indian regional languages remain static indicating the perpetuation of the social prejudices towards disability. These prejudices are also reflected in implementing measures for the mainstreaming of persons with disability in the Indian society. Disability movement is of very recent origin in India starting from the beginning of the 21st century. Former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi issued an order after the1971 War against Pakistan reserving 3 percent in government jobs for persons with disability. The positive gesture of the Prime Minister was sabotaged by the negative minded bureaucracy which interpreted that only C and D categories of jobs would fall under this reservation. According to this interpretation, persons with disability were eligible for the posts of peons, attenders, sweepers, etc. What a perverted mind of the bureaucrats? There were widespread protests against the abuse of the 3 percent reservation. Finally. The Persons with Disabilities Act was passed in 1995. Though it was a weak legislation the Act was hailed as a path breaking one. The Act specified that 3 percent reservation of jobs in all kinds of government jobs and in educational institutions including professional colleges, IITs and IIMs would be mandatory. Till that time not even one student with disability was admitted in any professional college in the country. This was the initial phase of the disability movement in India from charity to rights. Javed Abidi, who at that time was with the Rajiv Gandhi Foundation, is one of the architects of this shift in emphasis in the struggle for justice for persons with disability. The “invisible minority” of the large number of persons with disability was never considered important by the Census administration and it refused to include disability in the 2001 Census. The disability activists took the protest to the streets. L.K.Advani, the then Home Minister, intervened and for the first time disability was counted by the Census authority. However, there is gross under-enumeration of persons with disability even in the 2011 Census. The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, which became operative from April 2011, provides constitutional right to all children in the 6 to 14 age group in a neighbourhood school, suffers from half-hearted implementation and many loopholes for the reluctant elite schools to evade the statutory provisions to admit children with disability and children from poor economic background. The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2014 superceded the 1995 Act and it is considered a landmark law. But the critics say that the Act was sloppily drafted and was passed in a hurry keeping the 2014 elections in sight. One example is the 3 percent reservation for persons with disability in jobs and in promotions including entry to civil services. The government of India adopted a hyper-technical view and argued before the Supreme Court that reservation in promotions would affect the prospects of the persons with merit. The Supreme Court expressed its displeasure with this approach of the government and ordered that reservations would be applicable in promotions also. The UN General Assembly adopted the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities on 13th December, 2006. On October 1, 2007, India ratified the U N Convention which lays down the following principles for empowerment of persons with disabilities:

The 2014 Act is based on the principles of the UN Convention. But its implementation leaves much to be desired as was evident from the regressive stand taken by the government (both UPA and NDA) on the reservation issue before the Supreme Court. Malcolm Gladwell’s famous book “David and Goliath” (2013) has given impetus to persons with disability and other “underdogs and misfits” to face difficulties with courage, and spurred disability and other minority movements .Sudha Menon and Ferose wrote the book “Gifted” (2014) narrating fifteen inspiring stories of persons with disabilty, who transformed challenges into great opportunities with grit and determination. Malavika Iyer, who lost her hands and legs in a freak accident, has become a professionally qualified social worker and a designer of fashions ; Siddharth with cerebral palsy and “70 percent disability” always tried to cross the 70 mark in academic and professional life, whom former President Dr.Abdul Kalam addressed at a public gathering as “my friend ,the banker from Chennai” ; and Javed Abidi, despite being restricted to a wheel chair, is a leading figure of disability activism in India are some role models illustrated in the book. Fortunately these motivated persons have had the benefit of family support and financial backing. But there are many “Davids” without financial support to gain access to technology and quality medical care. Outside these circles of success are millions without any opportunity to overcome the challenges of disability. Recently, a political leader of great stature and a former Chief Minister of the state of Tamilnadu for the longest period M. Karunanidhi refused to attend the Assembly proceedings as there was no “disabled -friendly” facility for him, being bound to a wheel chair for the past few years. It is an irony that as Chief Minister he piloted the policy for the differently abled in the state. The present government led by the former opposition party ordered in February 2013 that all public buildings should have a slew of access-friendly facilities ranging from ramps to handrails within six months. But only about 1 percent of the public buildings in the capital city Chennai is disabled -friendly and not a single public transportation (bus) in the city is access-friendly to persons with disability. There is a huge gap between the promises of the central and state governments, and the ground reality. Recently the government of India announced a massive campaign “Sugamya Bharat” (Accessibility India) to sensitize people on accessibility issues concerning persons with disability, besides creating awareness on improving facilities for them. No doubt, it is a laudable initiative. But, like all other initiatives, will this also go the usual way? “While the Rest of the world has taken great strides in mainstreaming the differently abled into the larger contours of their society, life continues to be an uphill struggle for the differently abled in India (Menon & Ferose, 2014). Will the differently abled continue to be overburdened with the “handicapped” tag and live a life on the fringes, largely ignored by the Indian society and its political masters and the bureaucratic bosses? References 1. Albert,B., & Hurst, R. (2005). The Social Model and Poverty Reduction: Disability and the Human Rights Approach to Development. London: Department For International Development. 2. Charlton, J.L. (1988). Nothing About Us Without Us: Disability Oppression and Empowerment. Oakland: University of California Press. 3. Donnellan, C. (1982). Disabilities and Discrimination Issues for the Nineties. New York: McGraw Hill. 4. Drake, R.F. (1999). Understanding Disability Policies. London : MacMillan Press. 5. Duffy, K. (1995). Social Exclusion and Human Dignity in Europe. Strasbourg : Council of Europe . 6. Gladwell, M. (2013). David and Goliath :Underdogs ,Misfits and the Art of Battling Giants. New York: Little, Brown and Company. http://punarbhavain/index.php?option=com.content&view=article. Retrieved on 17-12-2014. 7. Laderchi ,C ., Ruggeri ,R., & Stewart ,F . (2003 ). “Does It Matter That We Do Not Agree on the Definition of Poverty ?: A Comparison of Four Approaches”. Oxford Development Studies, 31 (3):243-274 . 8. Langtree ,I . “Definitions of the Models of Disability”. www.disabled-world.com/ definitions/ disability models - php. Retrieved on 18-12-2014. 9. Menon ,S.,& Ferose,V.R. (2014). Gifted :Inspiring Stories of People with Disabilities. Gurgaon: Random House India . 10. Morris,J. (1991). Pride Against Prejudice: Transforming Attitudes to Disability. London : The Women’s Press . 11. Stewart ,F.,Barron, M .,Brown,G.,& Hartwell ,M. (2006). Social Exclusion and Conflict: Analysis and Policy Implications, CRISE Policy Paper. Oxford: Oxford University . 12. Thomas,C. (2003). Defining a Theoretical Agenda for Disability Studies. London: Disability Studies Association. www.mymdrc .org /models-of-disability .html Retrieved on 18-12-2014. www. plato.stanford. edu / entries/disability/ Retrieved on 18-12-2014. 13. World Health Organization. (1996). The World Health Report 1996 :Fighting Disease, Fostering Development. Geneva: WHO. Deepti Nair Secretary, CEWA, Chennai |

Categories

All

Social Work Learning Academy50,000 HR PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS. MHR LEARNING ACADEMYGet it on Google Play store

|

SITE MAP

SiteTRAININGJOB |

HR SERVICESOTHER SERVICESnIRATHANKA CITIZENS CONNECT |

NIRATHANKAPOSHOUR OTHER WEBSITESSubscribe |

MHR LEARNING ACADEMY

50,000 HR AND SOCIAL WORK PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed