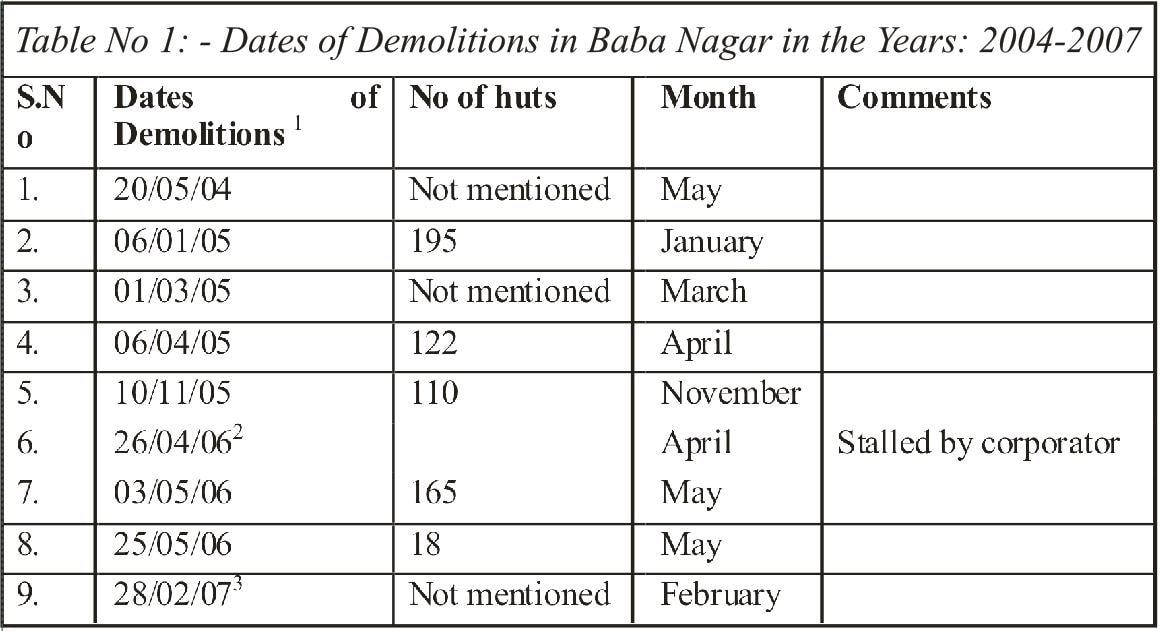

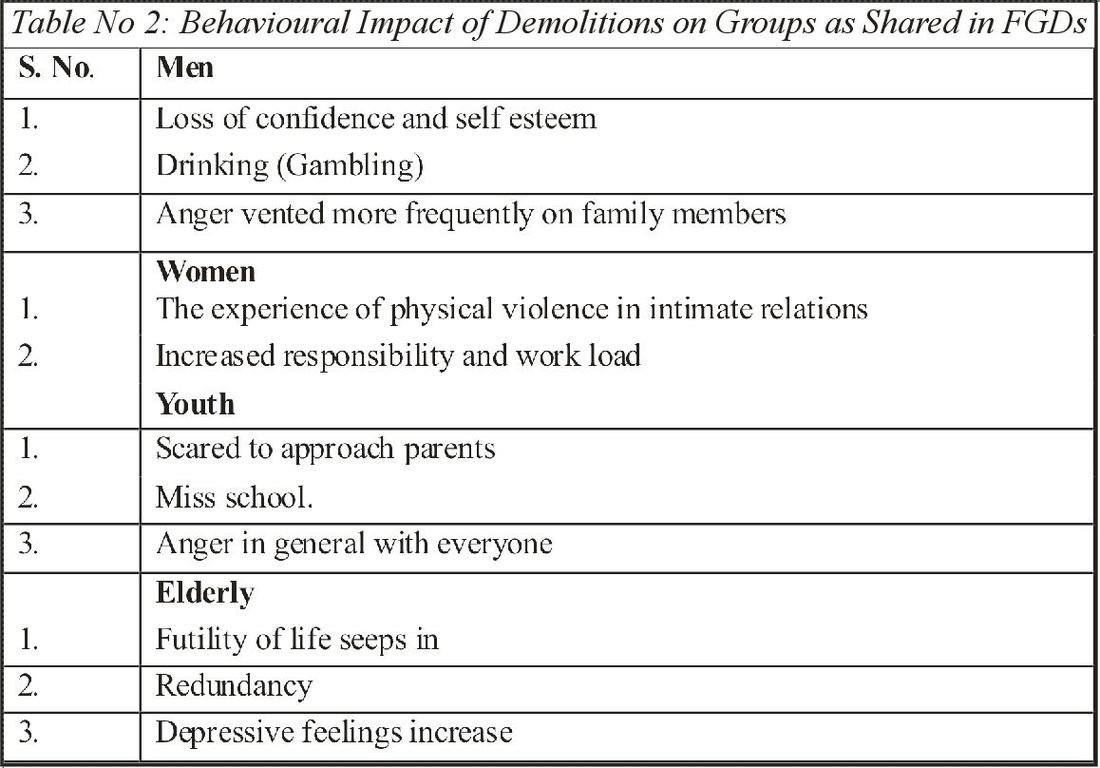

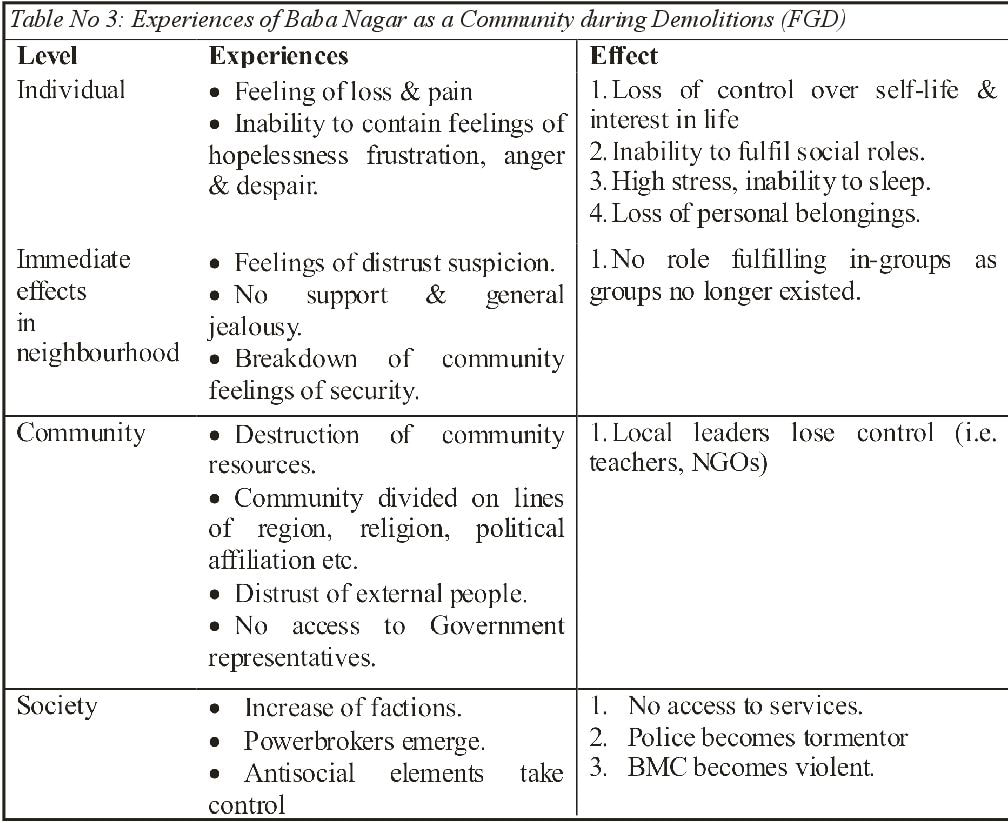

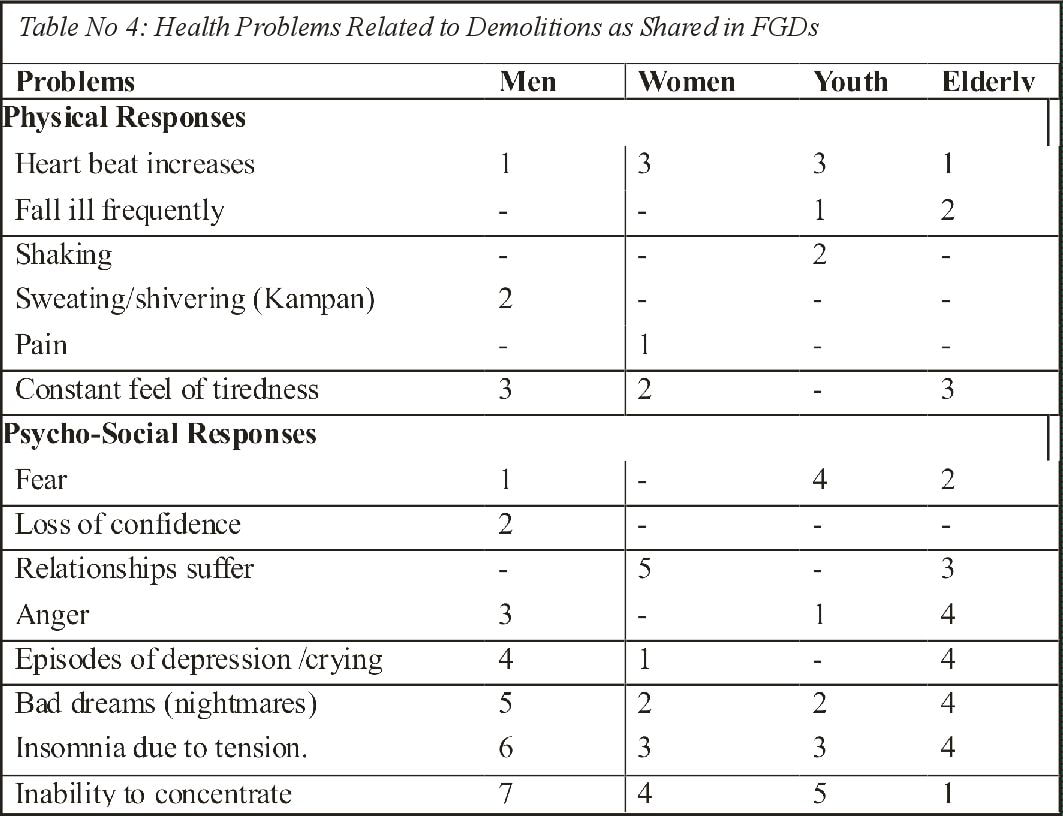

DESPAIR AND HOPE: COUNSELLING NEEDS OF THE ELDERLY IN AN URBAN SLUM EXPERIENCING DEMOLITIONS10/21/2017 Abstract: Elder neglect is a serious problem, however it is not a priority in the public health domain. This paper highlights the neglect the elderly experience slum demolitions which requires a structural analysis of various forces, the systems, structures and mechanisms that has a direct impact on their health and well being. It illustrates through a slum in an eastern suburb of Mumbai how elders on an average face more and some unique challenges besides lower incomes and higher health care costs, the problems they face in times of slum demolitions and the impact of reduced community support for the elderly. Qualitative data from a doctoral thesis , further explicates the experiences of elders residing in an urban slum who are forced to cope in the midst of inadequate social support and social isolation. On a concluding note, the author discusses how with the diminishing family's role as the major caregiver there is a need to evolve counselling services as a major component within the ambit for protection of the rights of the elderly. Keywords: violence, demolitions, elderly neglect and counselling needs. Introduction: The present paper is based on the experiences of elderly residing in a slum pocket - Baba Nagar, located in a cluster of slums collectively called Shivaji Nagar, Mumbai, established in 1974. Shivaji Nagar was developed as a slum by the Brihan Mumbai Corporation (B.M.C) or the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (M.C.G.M) for Project Affected Persons (PAP) from the main city. The land belongs to the municipality and is called ‘municipal land’. The entire area has both declared and undeclared slums. A ‘declared’ slum has legal recognition and hence is provided with some civic amenities such as street light, common water taps, a stand post meter for 10 persons/households and garbage disposal facilities. All the slums pre-1995 are recognized and post 1995 are deemed illegal and liable to be demolished by the authorities. Baba Nagar or Rafiq Nagar II is an extension of Rafiq Nagar I, which is recognized. All the residents of Rafiq Nagar I have photo passes and have been assured of ‘legal’ water and electricity connection in the future. With the coming of the Shivaji Nagar Bus Depot, the roads surrounding the slum have been paved thereby providing better accessibility and connectivity to other parts of the city/area. On the other hand, since Rafiq Nagar II or Baba Nagar came up after 1995, it is not recognized by BMC as ‘legal’. Baba Nagar covers approximately an area of 15,300 square meters, with over 1000 hutments. The BMC staff alleges that Baba Nagar has encroached on the land, which was allocated for the dumping ground. The dumping ground is located on land leased by BMC and is a prohibited area. The residents however vehemently refute this and claim that they have reclaimed the land by filling in the creek and are located on the fringe i.e., 10 meters away from the Deonar Dumping ground (the basic area for a no man zone around the dumping ground). The elderly residing in Baba Nagar, experience various forms of violence, from systemic to personal pervasively in their everyday lives and as stark events or outbursts of physical violence. In this paper they make sense of violence and explain it themselves in this paper. Elders for this paper are broadly defined as vulnerable adults having physical and cognitive characteristics that necessitate a specialized response strategy. While culturally, in India elders were respected for their wisdom and experience today these very elders are neglected, which impacts their ‘well being’ profoundly. As a result , they require varying degrees of assistance with activities of daily living, such as eating, dressing, bathing, grooming and toileting. Some suffer from incontinent of bowel and/or bladder or have chronic physical conditions that require ongoing monitoring. For some, cognitive decline may affect their ability to express him/herself to process information. They may have difficulty in articulating their needs and at times have problems in understanding the context of present issues. As a result,elders often tend to wander, have poor impulse control, or resist medical care or assistance with personal care tasks such as bathing or toileting. Issues which Impact the 'Well being' of Elders in Baba Nagar- To understand the issues that most impact the elders of Baba Nagar, a focus group discussion (FGD) was conducted with thirty elders, fifteen each of both genders. In the FGD, they instantly stated that the degenerating values in the present ‘kalyug’ are the most disturbing thing that affects them. The elders feel that they are often referred to as burdens by their family and hence consulted in limited community issues. Thus they feel they have limited social powers which often is over ruled by external political or economic power. They expressed concern over increased violent incidents both at the social and personal level. The elders felt that giving respect and the tradition of serving the elders has gone and is replaced by money power. One elderly lady shared ‘pehle to chua choot hoti thi to aana jana sab jagah kabool nahin tha, par aab to ye khud par ye rok tok lakar haram ki zindagi jite hai’ (in the earlier days untouchability restricted ones movement but in today’s time they put restrictions on themselves and live a stressful life). Thus, indicating that in olden time’s social interaction was regulated by sanctions imposed by the caste system, but these have diminished in the urban context as they are getting replaced by the younger generation’s frustrations and anger. The elder men also talked of erosion of values and thereby the increase of abuses. As one man shared ‘pehle to pyaar mohabat ki baatein sunne mein aati thein par aab to khali mar pit aur irshya ki baateein hi chaaron taraf phel rahi hein’ (In our days we heard about love and respect but these days one hears only of violence and jealousy everywhere). Many group members talked of ‘zahan aur mann mein bahut dukh dard hai’ which roughly translated means in my mind and heart there is a lot of sadness and pain. They emphasised on the lack of respect and created structural social inequalities, which unnecessarily isolated people. This was agreed upon by everyone, thereby endorsing that the prevailing culture has become in many ways one of violence rather than of caring. The elderly were the only group within the larger study which mentioned untouchability as a form of violence as it had deprived them of many opportunities because of which they feel not only are they suffering but along with them an entire generation is suffering too. Thus earlier untouchability was a crucial issue but now they seem to indicate that other issues occupy immediacy. Elders also mentioned general violence as an issue and were visibly disturbed by the increase in general violence, in the community. The hurt and resentment was evident when they stated family violence as being the most common form of violence. They stated that the old and the young (children) are the most vulnerable and thus most abused in the community. The elderly pondered over the causes of violence for quite some time and then came up with some astute observations. They shared that not only has manifest violence increased but the number of people being harmed under the guise of ‘mazhab aur tehzeeb’(religion and social regulations) has also increased. ‘Apne time mein aurat aur bachoon ko sarak par to haath nahi uthta tha…ghar mein chahe jitna bhi bair ho’(in our time women and children were not hit on the streets...no matter what tensions existed at ones home). They stated personal violence was hidden in their times and that getting personal violence out in the open was equivalent to suicide. They however quite aggressively denied that this could be the reason of the low visibility of violence in their times. Thus for the elders breakdown of families followed by general violence were two forms of violence which they clearly linked to systemic causes. This was followed by demolitions which they linked to poverty and unequal distribution of resources. The elderly saw criminal violence and communal violence also as an expression of lack of resources, inequalities and wide disparities. They said that when people see others having more than what they have, the whole mind set shifts from us to them and then to ‘mera aur tera’ (mine and yours). The elder women also saw domestic violence and prostitution as being linked to poverty. They said that those men who can’t support their families tend to be more violent and women who have been deserted have no option but to kill their ‘sharam’ (shame) to feed her family. Its apparent from the above that there are patterns of neglect experienced by the elderly due to the fall in values and the decline of respect for elders which included - not being informed of family decisions (isolation), no access to money, facing jibes from family members etc. It also reveals that elderly men were seen as more interfering and rigid in comparison to elderly women who were regarded as an asset for child care and whose interference was broadly limited to household chores. The sentiments shared by the elderly in the FGDs and shows how things could to be taking a turn for the worse in the years to come. Experience of Demolitions: Elders shared that demolitions was a form of violence that came into existence for them recently (as in the past 15 years). They described the days when Baba Nagar was a slushy area and they either with parents, as children or as young adults, hauled mud and concrete to fill up the area so that they could provide for the very children who now called them ‘useless’. They also stressed that as earlier the place was slushy, ‘the government would not want to risk dirtying their shoes’ coming and demolishing the place. This gives an insight as to how demolitions have become a tool ‘to remove unwanted people from wanted land after they have toiled to make unusable land usable’. This response clearly elucidates a deeper dimension of violence. They equated demolitions to a disaster. The difference being that most natural disasters are sudden where as demolitions are pre-planned and executed with the intent to cause damage. During Demolition it is often seen that people whose houses were demolished most often are taken by surprise and hence are completely unprepared to respond to the situation. As soon as the first house is demolished there is a collective cry of despair and helplessness. As the bulldozers wreak havoc one can sense the pain, loss and distress of the people who often try to break the police cordon to save their homes. One can see heated exchange of words turning into physical blows, women wailing, some are just too numb with shock to respond, children trying to find their parents for comfort which they are unable to provide, the elderly become mute spectators as they are unable to do much and the youth vent their anger by throwing stones at the bull dozer. As a result, the police arrests them and detains them for a day. Thus besides dealing with the trauma of demolitions one has to deal with random arrests by the police. The above experiences of demolition alert us to the powerful mechanisms of structural violence that create and maintain inequities over generations to produce suffering and damage which is slower, more subtle and more difficult to repair than direct violence alone. Elders shared that demolitions before 2004 were conducted by a demolition squad who would manually break down structures, with sticks and axes, which gave people time to save their belongings. They admitted that they were used to their hut being partially destroyed in these summary demolitions as they never ever constituted full scale eviction. In the recent demolitions, which took place with bulldozers and earthmovers, huts were flattened within a few hours, providing little time for people to save their belongings. With the methods and tools of demolitions becoming more powerful and harsher as seen in the 2004 demolitions, the violent intent of the state becomes clearer, as it is a change, which ensures damage that is more permanent. The timing of demolitions further elucidates state apathy. A majority of the people, 98% stated that demolitions happened every year in the monsoons (May-September) and summers (February-April). The official information on the dates of demolition (Table No: 1) shows that demolitions do happen approximately in the same months as reported by the people. Thus demolitions during monsoons are more traumatic as their belongings normally are lost in the creek and the chances of retrieving, repair and reuse is lesser for them. Living Conditions Post-Demolitions: Demolitions were often referred to as a nightmare and the trauma was visible every time the elderly talked about it. The first obvious action that most people took on getting to know of demolitions was to try to save their belongings. In the frantic scramble to save their belongings, one young girl stated that ‘the police beats everyone... children, elderly and women…in the process we get hurt and can’t retrieve our belongings.’ Demolition thus, further taxes the extreme critical situation and diverts the scarce resources available for food, health care and education. Post demolitions people stated they live under the open sky irrespective of the heat and rain, without food and water. The worst affected are the elderly and young children. This shows that people who in the normal course of life have limited access to basic services during demolitions, have even lesser food, no clean water, and are wilfully exposed to harsh weather conditions. Post 2004 the entire area was flattened and garbage dumped in the area demolished. Demolitions lead to competition for scarce resources and hence exploitation increases, personal security decreases and violence escalates. This, when coupled with a weak social support system and poor health care measures, contributes to the desperate plight of people. It leads to a complete breakdown of the social support system, thereby increasing the victimization, especially of the children, women and the elderly. It is evident that, with demolitions the already poor conditions of people of Baba Nagar are further exacerbated; violence here is difficult to measure/quantify as living in uncertainty for virtually indefinite periods can be an extremely torturous experience. The helpless feeling of not knowing how to handle the situation, in itself, proves to be very traumatic. This is further examined and elucidated in the next section. Self Reported Impact of Demolitions: When asked to enumerate the problems that the elderly associate with demolitions they reported feeling gloomy, angry and irritated at the entire situation. They said seeing the house that they had painstakingly built reduced to rubble and being covered with garbage was too much for them to endure. With tears in their eyes they recounted the painful days when along with the hardships at the work front they would still find time to build a part of their house every day. They all shared that they saw no point in living any longer, shows that thoughts of death were not uncommon. Thus, along with the obvious physical hardship, increased harassment by the ‘government agencies’, the episodes of violence and experience of trauma simply escalate during demolitions. Demolitions it is obvious affects people differently. Justifiably the coping mechanisms resorted by each group is also diverse. Data from the FGDs (Table No 2) which, at a very rudimentary level reveal that the elders understandably were visibly helpless, but felt more helpless when they had to bear the brunt of their children’s anger. They had to face ridicule from the younger ones for not being able to provide them with a ‘decent’ place to live. This made them feel redundant. They reported experiencing long periods of depression which made them want to end their lives soon. The group simultaneously reported experiencing anger and insecurity, but at the same time were hesitant to approach anyone for reassurance, thereby showing how violence increases the vulnerability of the already vulnerable adults. Thus, suppression at home and frustration with self all leads to violence towards self and others. It is apparent that the trauma of losing their fragile world to the bulldozer is no less than the trauma of any disaster. Facing demolitions regularly sometimes as often as every six months can be a terrifying experience for anyone. In the FGD the elderly group enumerated concerns ranging from lack of shelter, sanitation, health, education, employment and infrastructure post demolitions. After which the discussion elucidated (Table No: 3) how demolitions affected the lives of people. It was seen that demolitions not only changed lives of individuals, but also changed the way the community functions. Due to demolitions, family networks were severed; people reported feelings of tremendous distrust of immediate surroundings and external agencies. People admitted that in ‘normal times’ one is not consciously aware of the others origins. But after demolitions due to insecurity, one feels safe in one’s own ‘jamat’ or community. This further accelerates feelings of distrust and prejudices, which exaggerates cultural and political differences. Table 3 summarizes people’s experiences immediately after demolitions as shared by different groups in the FGD. From the discussion a structural understanding of the complex effects of demoliton as a form of violence emerges. It was evident that the internal structure of the whole community was destroyed and that people, especially children are living a life of instability, struggling to get some semblance of order in their lives. Life, according to them, has become doubly difficult. Elders in the community as a whole experienced emotional problems, trauma related symptoms, increased incidence of abuse, lower health status and exposure to harsh conditions. It leads to feelings of worthlessness and uselessness thereby disempowering people. Some shared experiencing a feeling of worthlessness and depressive feelings (kya mein itna bekar hoon, gya guzara hoon??-Am I so useless and inadequate?). Or an inability to sleep (ek to chain nahi, upar se khambakhat neend ur gayi hai…aur jisko neend garimat se aa bhi gayi to darawne sapne aaate hai- One there is no peace on top of that I have lost sleep and if by mistake I do get sleep its full of nightmares) as well as the inability to express grief (kya karoon, mein ro bhi loon to kya hoga..thak gaya hoon dukhi ho kar bhi- what should I do? Even if I cry what will happen.....I am tired of being sad). It is evident that demolitions affected the lives of people at different levels. The FGDs revealed that the same violent incident experienced by the same community has a different impact for every individual and group; with the same outcome i.e. all felt equally victimized. Specifically when asked to enumerate health issues related to demolitions the responses as shown in Table No: 4 clearly show that immaterial of gender and age, the community as a whole has suffered extensively due to demolitions. In the FGD, the elderly shared falling ill frequently. This indicates that elderly post demolitions when exposed to unusually long periods of heat and cold, their physical capacity to withstand stress and strain reduces considerably which results in frequent episodes of illnesses. The responses of the elderly reveal that they are most affected by demolitions and experience a higher impact psychologically. They reported having episodes of depression and crying, suffering from nightmares and insomnia due to excessive tension. They were the only ones to admit that because of these tensions, relationships between family members deteriorate considerably. They too reported experiencing an increase in heartbeat and a constant feeling of tiredness, besides an increase in their illnesses after demolitions.

The problems enumerated above show people post demolitions experience symptoms related to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), after experiencing a visibly traumatic event such as an accident or even war. Thus demolitions are not only traumatizing but also life threatening. When placed on a continuum, the effects of demolitions range from a deep sense of individual and communal helplessness, leading to high levels of aggression, violence and abuse. Literature in the area of traumatic experiences deals with a broad range of human responses to exposure to life threatening events. The dominant problem in available literature on traumatic experiences are that they are dominated by western experiences’, where violence is seen as a single event occurring within a relatively safe ‘society’ and thus assumes it is possible to move trauma survivors to a safe place in which they can recover. This is impossible for people experiencing demolition as a manifestation of structural violence. People experiencing demolitions have a long history of stress, violence, insecurity experienced against a background of threat and danger. Thus, victims of motor vehicle accidents, singular violent crimes and natural disasters cannot be compared with victims of demolition, xenophobia, ethnic conflicts etc. Henderson (1998) elucidates this while describing the experience of civil conflict as a complex layering of broken bonds and the accumulation of betrayals of trust. She explores Reynolds’s work, which has cited a wide range of experiences of people in South Africa during civil conflict which, ranged from family fragmentation, family violence, state violence such as forced removals, detentions, torture and more recently civil violence. According to Henderson then, civil war thus becomes the very context in which healing must take place. The same holds true for the people of Baba Nagar. Chikane (1986) introduced the concept of CTSD – i.e. continuous traumatic stress disorder as a contrast to PTSD where as Herman (1992) on the other hand, speaks of complex traumatic stress Disorder as a term which encapsulates some of the difficult realities of individuals who are exposed to repeated, multiple and prolonged trauma. This concept breaks the important assumption that traumatic stress results from a single shocking event in an otherwise safe environment. It, however, stops short of grappling with the complexity of inter-relationship of all kinds of violence occurring simultaneously. Thus, the stresses emerging from leaving a safe haven cannot be equated to a singular experience of illegal detention in a police station. This highlights the fact that violence cannot be a simple matter of degree of difference. It has to go a step beyond. A realistic understanding of a violent situation thus would be where one recognizes that a person would have to remain in the same situation and the person’s own resourcefulness in the face of violence is important. This view emphasizes upon the fact that any intervention which disrupts coping mechanisms rather than strengthening them, no matter what they intend to do is potentially dangerous. These are the very underlying assumptions of structural violence and this very approach was missing in the strategy of NGOs who were constantly projecting prevalence of malnutrition and rise in infections, while mobilising relief post demolitions. The responses of people clearly show that they had experienced trauma and for them, emerging from these symptoms was more difficult that the ones the NGOs were summarily targeting. Thus demolition is a continuous and complex situation of violence within which people have to cope with the stress and impact of violence. This paper shows through the experiences and symptoms shared by the elders in the FGDs clearly reveals that just as in any other traumatic event, post demolitions not everyone experiences the event in the same way. Elders vis-a-vis others continue to experience symptoms months and even years after the traumatic event. People of Baba Nagar post demolitions traverse a broad range from retrieval of horrific memories, including intrusive thoughts to flashbacks and nightmares. The paper only gives an overview of the combination of mechanisms underlying demolitions and its effect on the elders of Baba Nagar. This is evident from a statement made by an elder woman who said ‘roz ka marna, marna nahi hai…..shamshan ghat pe rehna ulfat nahin hai… muut (excreata) ka kahna uljhan nahin hai par yeh roz ka marna maut se badtar hai’. She says that the death that they die every day is not seen as death despite the fact that they stay on the cremation ground, eat filth, live a life worse than death and this life is worse than death. The paper thus, illustrates the need to evolve multiple counselling strategies for the community in general and for elders in specific who till date have not emerged from the trauma of demolition’s. Conclusion Demolition as it can be seen triggers a host of other issues, which lead to conflicts and has become synonymous with being uprooted and experiences of violence. Demolition has aggravated the already fragile situation, and has become a ripe ground for ethnic/religious/caste tensions. Traumatized by the recurrent demolitions, elderly especially, are deprived of an opportunity to function normally. The article stresses the necessity of counselling to reach out to the needs of frail elders who required special support during demolitions as they could not carry out their daily life functions after the demolitions not only due to due to mental and physical health issues but due to depression and trauma. This section of the slum population has been overlooked as many elders, are so debilitated and neglected that they do not advocate for themselves or access the on-site services. They languish on their cots unnoticed, usually suffering in silence as busy volunteers and staff attended to the needs of more able-bodied evacuees. References

Dr. Ruchi Sinha Associate Professor and Chairperson, Centre for Criminology and Justice. Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, India. |

Categories

All

Social Work Learning Academy50,000 HR PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS. MHR LEARNING ACADEMYGet it on Google Play store

|

SITE MAP

SiteTRAININGJOB |

HR SERVICESOTHER SERVICESnIRATHANKA CITIZENS CONNECT |

NIRATHANKAPOSHOUR OTHER WEBSITESSubscribe |

MHR LEARNING ACADEMY

50,000 HR AND SOCIAL WORK PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed