|

Abstract We live in a world that is increasingly interconnected through the processes of globalization. The processes are bringing together people from many different cultures and the interactions that take place can often lead to conflict if not managed properly. Further, globalization can also lead to increasing marginalization of the weaker sections of society and conflicts around basic resources such as water and food. In this paper, the role that community development can play as an effective response to some of the negative impacts of globalization is examined. It is argued that traditional forms of community development have to be critically examined in the light of new and emerging forms of community and that more inclusive forms of community development have to be developed. The model of culturally competent community development is suggested as an effective approach in this context. Keywords: Community Development, Globalization, Culture, Cultural Competency. Introduction Over the last millennium and the beginning of the present one, human interconnectedness and interdependence are increasing at an extraordinary rate and have become a part of daily life and all that happens in this planet is no longer a limited local event leading to a reorganization of lives, actions, organizations and institutions along a local-global axis (Beck, 2000). This paper begins with a discussion of the phenomenon of globalization and focuses on some of the key aspects of it that impact negatively on the lives of poor and marginalized communities across the world, including aspects that are based on neoliberal ideology and those based on global risk. The last aspect of globalization examined in this section is that involving the movements of people as migrants both internally and externally to the nation-state. The concepts of cultural identity and cross-cultural conflict are introduced as issues that need to be addressed so as to enable communities to manage the negative impacts of globalization. Community Development is then looked at as one of the commonly used approaches that can facilitate communities to develop power and establish some level of control over their own lives. Some of the strengths of community development are discussed and also some of the issues in present-day practice. Significant focus areas for future practice are also identified. A model of cultural competence that has recently been developed by the author is then presented and its application to community development discussed. The paper closes with the argument that community development needs to incorporate ideas of social inclusion and cultural competence if it is to continue to be relevant in the changing global context. Globalization A number of different concepts have been used to explain the nature of these interconnections. Some of these include Wallerstein’s notion of a World System, Roland Robertson’s ‘Glocalisation’ and Arjun Appadurai’s ideas of a range of ‘scapes’ involving the movements of people, finances, media, technology and ideas (Gopalkrishnan, 2003). At the simplest level, globalization can be understood as the ‘widening, intensifying, speeding up and growing impact of world-wide interconnectedness’ (Held, 2010). While globalization is a very complex process involving a number of actors interacting at a number of levels, there are many scholars who would argue that one of the primary drivers of present-day globalization is neoliberal ideology, which has become the predominant ideology of our times in most parts of the world (Heron, 2008; Mendes, 2003). This ideology focuses on the centrality of the free market and strongly suggests that most, if not all, social problems can be managed by the ‘invisible hand’ of the market. Further, it also recommends that economic forces need to be insulated from the State as stable markets can only be assured when economic decisions are removed from politics (Gill cited in Harmes, 2006). The term ‘Neoliberal globalization’ is an appropriate one that will be used in this article to focus on those aspects of globalization that are clearly driven by the neoliberal agenda. Also the terms Minority World (referring to the per-capita income-rich highly industrialized countries where the minority of the world live) and Majority World (referring to the per-capita income-poorer, less industrialized countries where the majority of the world live) will be used rather than the traditional and rather inaccurate ‘developed/underdeveloped’ or ‘West/East’ terms. These terms were developed in the early nineties by Shahidul Alam, a writer and activist photographer from Bangladesh, and challenges some of the assumptions that are inherent in the other terms (Bowen, 2009). Clearly, the rapid advances in information and communication technology and infrastructure have been central to the rapid growth of globalization in general and neoliberal globalization in particular. However in the case of the latter, the structures that emerged out of the Bretton Woods conference in 1944, such as the International Monetary Fund and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (part of the World Bank Group) and others that followed such as the Asian Development Bank, continue to act as the cutting edge of neoliberal globalization and push its agenda across the world (Beck, 2000). There are a number of processes involved in terms of furthering the neoliberal agenda including Structural Adjustment Programs that are imposed on debt-ridden, and often poorer, nations; the flows of Foreign Direct Investment that take their signals from international credit ratings; as well as international trade agreements like GATT and TRIPS that allow for governments to be sued for infringing on corporate rights (Harmes, 2006). The ability of the nation-state to take decisions on behalf of their citizens is increasingly being circumscribed by a number of these processes, and many governments are implementing neoliberal policies that involve deregulation of markets, privatization of public enterprise, reduction in direct taxes and cuts in public spending (Dominelli, 2010). Neoliberal globalization has considerable impacts on the communities across the world. George Soros, who has profited enormously from global flows of currency, especially in crises like Black Wednesday in the UK and the Asian Financial Crisis, has this to say about neoliberal globalization: First, many people, particularly in less-developed countries, have been hurt by globalization without being supported by a social safety net; many others have been marginalized by global markets. Second, globalization has caused a misallocation of resources between private goods and public goods. Markets are good at creating wealth but are not designed to take care of other social needs. The heedless pursuit of profit can hurt the environment and conflict with other social values. Third, global financial markets are crisis prone. People living in the developed countries may not be fully aware of the devastation wrought by financial crises because……..they tend to hit the developing economies much harder. All three factors combine to create a very uneven playing field. (Soros, 2002, pp. 4-5) In hindsight, as Soros wrote this prior to the Global Financial Crisis, the impacts on the poor and marginalized in the richer countries are also very significant and point to ‘new forms of inequality which, increasingly, will have to be tackled transnationally (Beck, 2007b, p. 1). The vision of the 20:80 society raised by the 1995 International Forum organized by the Gorbachev Foundation in San Francisco is one where 20 percent of the world, irrespective of the country, will participate in life, earnings and consumption, while 80 per cent of the population will have no work and will not participate in society as we know it today (Martin & Schumann, 1997). The reality of this becomes more stark when we consider that Dominelli’s (2010) criticism of the fact that the top 20 percent of the world’s population has already accumulated 86 per cent of the wealth while the bottom 20 per cent have to make do with 1.3 per cent of the total wealth. Another aspect of globalization that presents significant challenges to communities in both the Majority and Minority Worlds is the globalization of risk, where risks are no longer local and the impacts of crisis are not localized (Beck, 2007a). The world is facing a number of overwhelming problems, such as climate change, energy and food insecurity, loss of biodiversity, poverty and population growth, all of which have global impacts and shape the way that we lead our lives (Beddington, 2009; Coates, 2003). Further, these issues are further problematic in that they impact disproportionately on the poor and marginalized in society as well as disproportionately on nation-states in the Majority World. Doherty and Clayton (2011) point to this in the impacts of climate change where they argue that the impacts fall more on the poorer sections of society. Similar issues are raised in disaster intervention research where poorer people, ethnic and racial minorities, people with disabilities as well as those living in the Majority World as against the Minority World are more likely to experience more severe impacts of disasters (Haskett, Scott, Nears, & Grimmett, 2008). Another area of note in the notion of global risk is the concept of the ‘export of risk’ from privileged societies to less privileged ones, both within and across national borders. Ulrich Beck (2007a, p. 693) provides some examples of these including the export of toxic and other wastes, export of dangerous and/or polluting industries, as with the export of controversial products and research as well as the export of torture and suggests that ‘the poorest of the poor live in the blind spots which are the most dangerous death zones of world risk’. The globalization of the movements of people is another aspect of globalization that is intrinsic to this discussion. Arguably, migration of people is the most visible of the forms of global movements and is the one that is most controversial in terms of communities as well as the nation-state (Turner & Khondker, 2010). The International Office of Migration (2011) states that there were over 214 million international migrants in 2009 as against 191 million in 2005, and that internal migrants account for over 740 million migrants. These figures are probably on the lower side, given the difficulty of identifying internal migrants and the rapid increases in movements of people from rural areas to urban areas across both the Minority and Majority Worlds. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees also identifies over 35.4 million people of concern across the world including refugees and internally displaced people (UNHCR, 2011). Besides the movements of people forced to migrate due to crises like war and natural disasters, as globalization makes the relative differences in income levels more visible to greater numbers of people and national economies are less able to provide for their citizens due to the adoption of neoliberal approaches, there are increasing pressures of people wishing to move between nations in search of better paying work (Solimano, 2010). However, Cohen (2006) suggests that their movements continue to be constrained by institutional migration arrangements that only allow certain kinds and numbers of migration flows to take place. Increasingly the movements of skilled migrants in categories that are valued, such as business and information technology, are privileged while the movements of unskilled workers continue to be restricted (Castles, 2013). International migration flows have also become increasingly complex with movements from the Minority World to the Majority World, extensions of the sex trade across international borders, movements of contract labor on short-term contracts to countries such as those in the Middle East, as well as illegal and hidden forms of migration (Turner & Khondker, 2010). Esipova, Pugliese, and Ray (2013) report that internal migration does not draw as much attention due to its impact within nation-states rather than across them and the difficulty of identification, but internal migration has significant impacts on both those that move and the host populations. In India, for example, where the population according to the 2011 Census is 2.1 Billion, internal migrants represent 28.5 percent of the population or 326 million people (UNICEF, 2012). These are large numbers and represent significant impacts on the receiving populations and communities. Castles has argued that migrant populations are often different from the receiving populations on many counts, such as differences across the rural/urban divide, different cultures, different languages, dress codes and sometimes even in legal status, as with guest workers in countries like Turkey (2000, p. 278). These differences can impact on the nature of ethnic relations within society and can even lead to conflict based on cultural difference. The term ‘culture’ is used here is in its broadest sense as ‘an abstract concept that refers to learned, shared patterns of perceiving and adapting the world which is reflected in the learned, shared beliefs, values, attitudes, and behaviours characteristic of a society or population’ (Fitzgerald, Mullavey-O’bryne, & Clemson, 1997, p. 3). It includes the total cultural domain of a society including language, race (as a cultural construct and not as the antiquated biological one), religion, nationality and socio-economic status as some of the factors of differentiation that are incorporated into the term, and app of which then provide a shared worldview (Bean, 2006). Cultural identity is also dynamic and flexible and can involve the notion of multiple identities that people slip in and out of depending on the context. In another publication (Gopalkrishnan, 2013), the author has explored this idea of dynamic cultural identity in the context of Indian ethnic identity where identities grounded in caste, in religion, in language, in tribes, and in Aryan/Dravidian differences were described with the argument that communities and individuals within them may change identities for a number of reasons. But, as that may be, governments of counties across the Majority and Minority World continue to have to deal with populations and communities that are increasingly culturally diverse (Castles, 2000) Cultural differences assume major significance when globalization causes cultures to interact more closely. Some of these are in the form of increasing interactions as through the media and through communications and the Internet, which can be turbulent and in some cases, lead to cross-cultural conflict (Cottle, 2006). But other interactions, such as those between migrants and receiving populations and between different groups of migrants, can lead to conflicts for scarce resources and cultural conflicts (Demeny, 2002). Robert Putnam describes this in the context of the Minority World as: Ethnic diversity is increasing in most advanced countries, driven mostly by sharp increases in immigration. In the long run immigration and diversity are likely to have important cultural, economic, fiscal, and developmental benefits. In the short run, however, immigration and ethnic diversity tend to reduce social solidarity and social capital. (Putnam, 2007, p. 137) The movements of migrants, accompanied by their own cultures and stories can lead to new forms of social exclusion based on cultural interpretations of who is in and who is out, a widespread example of which can be seen in the form of attitudes towards migrants of Islamic background particularly in countries of the Minority World (Hage, 2002). Babacan (2005) argues that racism and discrimination also play their roles in terms of escalating the differences between individuals and groups in society. The development of racist movements across the world can often to be linked to the fear of the ‘Other’ which comes into play in the context of migration, and the development of the ‘One Nation’ Party in Australia is one such example of migration politics (Quinn, 2003). Similar examples of the construction of the ‘other’ as the hated, often perceived as inferior, people in society may be drawn from countries in the Majority World, such as the identity politics centred on religion that has resulted in thousands of deaths in India over the last few decades (Gopalkrishnan, 2013). The attacks on Bengali Muslims in Assam and the xenophobic political attacks on Bihari migrant labour in Mumbai are some recent examples of the effects of fear-mongering against the other in the context of internal migration that are drawn from India (OADBS, 2012). These issues gain greater significance as the rate of interactions that are part of the globalization paradigm increases exponentially. The preceding discussion on the complex nature of the impacts of globalization involving issues of equity, management of risk and cultural diversity raises the need for effective responses that can help to manage or at least alleviate many of the negative impacts on individuals, families and communities. These approaches need to be socially inclusive so that those marginalized in society on various grounds can be involved as part of the process. One such approach is discussed in the next section. Culturally Competent Community Development Many of the problems described earlier are related to power or the lack of power in society. Ife and Tesoriero (2006) point to the issues of lack of power in many communities that is inherent in the present global society and discuss eight aspects of power including: Power over personal choices and life chances; Power over the assertion of human rights; power over the definition of need; Power over ideas; Power over institutions; Power over resources; Power over economic activity; and power over reproduction. They argue that class, gender and race/ethnicity are three key elements that must be viewed in terms of structural disadvantage and lack of power in society. Community development approaches that espouse values of empowerment and ant-oppressive practice are a major force in terms dealing with these issues of lack of power and can enable communities to react effectively to the problems inherent in a globalized world. Susan Kenny (2011b, p. i7) describes community development as ‘born out of a commitment to practicing ways of empowering people to take collective control of their own lives’. The focus on transformational practice that is inherent in community development approaches, practice that is based on a clear set of values, involves collaboration between stake holders and is democratic in nature, makes these approaches very effective to resist the negative aspects of globalization (Forde & Lynch, 2013). Community Development can be seen to be the ‘process of establishing , or re-establishing, structures of human community within which new ways of relating, organizing social life, promoting human rights and meeting human needs becomes possible’ (Ife & Tesoriero, 2006, p. 2). Bhattacharya further attempts to bring together a conceptualization of what community development is and what it strives towards by describing community development as solidarity and agency, where solidarity refers to a shared identity (derived from place, ideology, or interest) and a code of conduct or norms, while agency is the ‘capacity of people to order their world, to create, reproduce, change and live according to their own meaning systems…’ (2004, p. 12). While the sentiments presented in these definitions are very attractive, the reality is that community development practice does not often live up to the vision. The reasons for this are many and some of these are embedded in the ways in which neoliberal ideology has co-opted non-governmental organizations (NGOs) through inflexible funding arrangements (Ledwith, 2001). At another level, the very term as been co-opted by the mainstream to refer to governmental programs (often based on top-down decision making) such as the large Community Development Programs of the Indian Government that seek to achieve developmental goals while maintaining the status quo in the context of power relationships in society (Andharia, 2007). Interestingly enough, it is in the countries of the Majority World that small-scale community-based and community-driven development approaches have been demonstrated to have been very successful such as the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) in India, the Orangi slum improvement project in Pakistan and the Iringa Nutrition project in Tanzania (Mansuri & Rao, 2004). While projects like that of SEWA have grown considerably over the years and do not necessarily reflect the traditional concepts of community, they continue to represent new opportunities for communities to engage with the globalized world. In earlier work (Gopalkrishnan, 2003), the author has argued that community development has an extensive role to play in terms of managing the negative impacts of globalization especially the trends towards marginalization of the weakest sections of world society. As Joseph Stiglitz, former Chief Economist at the World Bank, has stated, globalization has had a devastating effect especially on the poor in the Majority World, and yet there is enormous potential for good in what he calls ‘globalization with a human face’ (Stiglitz, 2002). Community Development as an approach can work towards this if focus is maintained on the following: • The mandate of the people it represents: For any action to be effective it must have the mandate of the people it represents. This would mean using clearly defined principles of people’s participation to gather information and directions for work (Cornwall, 2008). Structures of participation have to be created that empower the individual and the community and enable their concerns to impact on macro-economic policy (Bhattacharya, 2004). • The effective use of technology: Some of the strengths of technology are its ability to inform as well as to bring similar-minded people together. Television, radio, the telephone and the Internet provide numerous opportunities that need to be exploited more in the pursuit of a more equitable world. On the negative side, it must be noted that some channels of communication, such as newspapers and television, are tightly controlled in private hands, and also that millions of poorer people around the world have no access to most forms of technology (Castells, 2003). While this presents difficulties of access, there have been numerous cases of mass movements across the globe that have used technology to their advantage such as the Indigenous communities and the S-11 anti-globalization movements (Held & McGrew, 2002). • Global Civil Society: Communities must not only work at the local level but work towards a global civil society bound by codes of global governance and working towards a more equitable society (Bhattacharyya, 2004). International governance has to function under the same principles that democratic national governments do (Held & McGrew, 2002). Global governance has to protect the interests of the less powerful and not just those of the rich and powerful nations. Global movements need to be distinguished from market economics and used to strengthen those initiatives that are already working globally to improve the quality of life of every person. These include the United Nations, environment movements, human rights movements and other international social movements. In addition to these focus areas, the concepts of social inclusion and cultural competence need to be included in community development approaches to make them more effective. In the first section of this paper, issues of cultural conflict, social exclusion, racism and discrimination were raised as intrinsic to the globalization paradigm. Based on my many years of community development experience across countries in both the Majority World and the Minority World, I would argue that traditional community development approaches, workers and organizations are ill-equipped to deal with these issues. Communities can be very insular and can develop capacity within themselves at the cost of the outsider or the marginalized ‘other’. Much of the literature in the field tends to focus on the primacy of Indigenous knowledge and ideas of multiculturalism (Ife & Tesoriero, 2006), both of which are highly desirable aspects of community development. However, they do not work well towards ensuring social inclusion in the context of cultural diversity. The term ‘social inclusion’ used here refers to people being able to participate as ‘valued, appreciated equals in the social, economic, political and cultural life of the community (i.e. in valued societal settings) and to be involved in mutually trusting, appreciative and respectful interpersonal relationships at the family, peer and community levels’ (Crawford, 2003, p. 7). When cultural identity creates divides within and across communities, social inclusion becomes very difficult to achieve, even in rural Indigenous communities that have solidarity among most of their members but have a few that are not part of the mainstream. As an example, when the author was working with remote communities the State of Orissa in India, caste would often provide a reason for otherwise cohesive village communities to try and exclude some of the families from community-based housing projects. In other cases, differences in tribal identity would cause similar situations. It is in this context that I would argue that the inclusion of ideas of cultural competency in community development can make for better outcomes in terms of social inclusion. One of the earlier explorations of cultural competence, which has considerable relevance today, describes cultural competence as ‘a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes and policies that come together in a system, agency, or amongst professionals and enables that system, agency or those professionals to work effectively in cross-cultural situations… A culturally competent system… acknowledges and incorporates- at all levels- the importance of culture, the assessment of cross-cultural relations, vigilance towards the dynamics that result from cultural differences, the expansion of cultural knowledge, and the adaptation of services to meet culturally-unique needs’ (Cross, Bazron, Dennis, & Isaacs, 1989, p. iv). Several other scholars have defined cross-cultural competence more recently but this early examination continues to be the most comprehensive and most cited in the literature. Cross-cultural situations that arise with increasing frequency in a globalized world essentially bring two or more worldviews into close contact, and cultural competence can provide the bridge between these worlds in terms of the requisite structures, attitudes, knowledge and skills. It exists in within a process of interactive learning across cultures and is an ongoing process or as Lum (1999, p. 175) says, cultural competence “is a process and arrival point.” Most of the models of cultural competence focus on four areas of cultural competence: • Self-awareness of the worker’s own values, biases and power differences with clients. This includes recognition of the worker’s own worldview, that they are also culturally constructed, and how that impacts on the interaction with the client, levels of ethnocentrism, an understanding of power and how it shapes thinking as well as an understanding of how this self-awareness will lead to more meaningful interactions. • Knowledge of the practice environment, the helping methods and the client’s culture. This would include knowledge about the culture that the client comes from as well as more generalized knowledge about how cultures vary and interact with each other. A common problem here is of cultural stereotyping which has the implicit assumption that all people from one culture share the same characteristics, an assumption that is often incorrect and leads to cross cultural conflict. • Skills in verbal and non-verbal communication and • Inductive learning based on the worker- client interaction (Bean, 2006; Gopalkrishnan, 2006; Lum, 1999). While these levels of cultural competence are a good starting point in the discussion, there are other aspects that need to be further unpacked to develop this concept further and to make it more effective in different contexts. For example, it could be argued the basic attitude of the worker of worker or of the organization, non-governmental or otherwise, could be problematic and this would not be dispelled by the traditional means of knowing about the client’s culture and developing the skills to work with it. Further, the knowledge has to extend to the historical context so as to understand the power differentials that exist in society and how they impact on different sections of the community (Ife & Tesoriero, 2006). The skills that are discussed in the literature are also inadequate in that communication skills are only one kind of skill required by the culturally competent worker. Also as suggested by Graf (2004) cultural competence must have the affective dimension (as related to the emotions), the cognitive dimension(as related to knowledge and reason) and the behavioral dimension ( as related to skills and practice). The literature also maintains the focus of development of cross-cultural competencies on the worker and the agency, while I would argue that in the context of community development it is important for people in the community to develop these competencies too. To address the inadequacies of the present models the author has developed the AKS model of cultural competence that clarifies some of these issues. The AKS model of Cultural Competence (Bean, 2006; Gopalkrishnan, 2006; Graf, 2004)

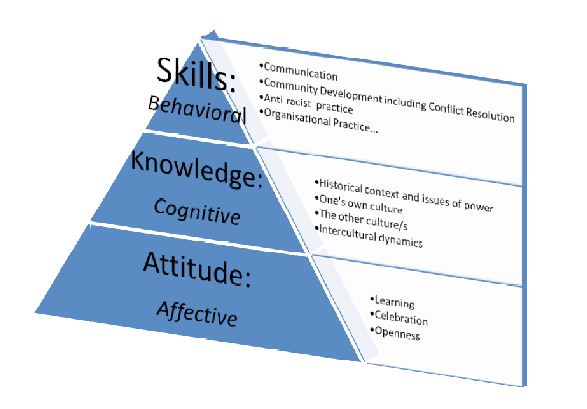

The nature of this paper does not allow for a lengthy analysis of this model but a brief summary is presented for clarity. This model begins with the affective dimension as there is considerable scholarship to show that the right attitude is central to the development of cultural competence (Bean, 2006; Gow, 1999; Landis, 2008). While the literature suggests that appropriate attitudes have to be developed through training, I would recommend that attitude be a starting point, a part of the process as well as an end point. An interactive learning attitude is one part of this where all parties are constantly learning, whether in a training environment or in a real-life interaction (Gow, 1999). Also attitudes of openness to difference and celebration of difference are central to this, as against many officially stated and very patronizing attitudes of tolerance of difference (Babacan H., Gopalkrishnan N., & Trad-Padhee J., 2007). The second aspect of cultural competency relates to the cognitive dimension or knowledge, beginning with that already mentioned earlier regarding the individual’s own culture, values, biases, and position of power as well as knowledge of the other culture/cultures that they will be interacting with (Bean, 2006). Knowledge of ethnocentrism and stereotyping is also part of this. Knowledge of history of the cultures and their experience of colonization and racism and discrimination is also important to get a true understanding of the present (Hollinsworth, 2006). And finally, the knowledge of how the cultures have been interacting and the dynamics of the present interactions needs to be explored. In the behavioral dimension there are a range of skills needed. Some of these are the micro-skills of communication that can be adapted to work across cultures (Ivey, Ivey, & Zalaquett, 2010). Others are more broad based skills required to enhance community development through increased participation, building community capacity and social inclusion (Kenny, 2011a). Work involving the challenging of racism and discrimination has its own need for a range of skills (Gopalkrishnan, 2008). And for the workers within organizational structures such as NGOs and government departments, the skills of organizational practice to enable them to work effectively within the organizations and ensure that the organizations are also culturally competent (Nybell & Gray, 2004). In the field of community development, these areas of attitude, knowledge and skills need to be developed at several levels including the individual, the professional, the organizational and the systemic (NHRMC, 2006). This could be through several processes including training, inclusion in participatory processes like PRA, or as part of organizational change processes. At the individual level, cultural competence can be nurtured among all stake holders including people in the community, especially the leaders and the gatekeepers, community development workers, support staff as well as senior staff of the various organizations involved such as NGOs and funding agencies. At the professional level, professionals working with communities such as social workers, public health workers, doctors, community development and rural development workers, among others, need to have cultural competence standards as part of professional standards and also have cultural competence built into the curriculum of their professional degrees. At the organizational level the organizational culture should value cultural diversity and the management of the organization is encouraged to develop diversity within the organization as well support work across cultures outside the organization. Ideas around community participation in organizations would be very useful in this context. And finally, at the systemic level, there is a concerted effort to develop appropriate resources, policies and procedures and also provide sufficient resources to support culturally competent practice. Community development practice that incorporates these dimensions of cultural competence is likely to prove to be able to work effectively with many of the impacts of globalization and ensure that the poor and marginalized in society do not get left behind in the race towards a better future. As discussed earlier, the economic effects of neoliberal globalization can and does have disastrous impacts at the local level, impacting most grievously on the poorer sections of societies or those marginalized due to lack of power (Soros, 2002). The lack of distributive justice is exacerbated by the extension of risk at a global level, where the poor and marginalized are affected the most by global problems like climate change and also by the export of risk from wealthier nations to poorer ones and from wealthier neighborhoods to more marginalized neighborhoods (Beck, 2007a). Increasing cross cultural interactions caused by the processes of globalization, such as migration, can lead to further issues of conflict and struggle within and across communities that are rapidly changing in the face of global forces. Culturally competent community development practice provides the opportunity to facilitate the growth of socially inclusive communities that are capable of drawing on their own resources to gain power over resources and decision-making that impact on their lives. It can strengthen the basis for movements that work towards ‘globalization form below’ or the notion of ‘globalization with a human face’. It can challenge many of the disturbing trends that we see of political power built on racism, discrimination and hate of the ‘other’. And finally, it can work towards the vision of a better, fairer and more just society. References 1. Andharia, J. (2007). Reconceptualizing Community Organization in India. Journal of Community Practice, 15(1-2), 91-119. doi: 10.1300/J125v15n01_05 2. Babacan, H. (2005). Challenges of Inclusion: Cultural Diversity, Citizenship and Engagement. refereed proceedings of International Conference on Engaging Communities. Retrieved from http://www.engagingcommunities2005.org/ab-theme-10.html 3. Babacan H., Gopalkrishnan N., & Trad-Padhee J. (2007). A Guide for Community Workers in Building Cohesive Communities. Australia: Multicultural Affairs Queensland 4. Bean, R. (2006). The Effectiveness of Cross-Cultural Training in the Australian Context. Canberra: Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs. 5. Beck, U. (2000). What is Globalization? Cambridge: Polity Press. 6. Beck, U. (2007a). Beyond class and nation: reframing social inequalities in a globalizing world1. The British Journal of Sociology, 58(4), 679-705. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00171.x 7. Beck, U. (2007b). In the New, Anxious World, Leaders Must Learn to Think Beyond Borders. The Guardian, (13 July 2007). Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2007/jul/13/comment.politics 8. Beddington, J. (2009). Food, Energy, Water and the Climate: A Perfect Storm of Global Events? Sustainable Development UK 09 Retrieved 12/09/2011, 2011, from http://www.dius.gov.uk/ news_and_speeches/speeches/john_ beddington/perfect-storm.aspx. 9. Bhattacharyya, J. (2004). Theorizing Community Development. Journal of the Community Development Society, 34(2), 5-34. 10. Bowen, A. (2009). The Privileged Westerner’s guide to talking about the rest of the world. THIS Retrieved 26/7/2013, 2013, from http://this.org/magazine/2009/07/16/third-world-developing-vocabulary/ 11. Castells, M. (2003). Global Informational Capitalism. In D. Held & A. McGrew (Eds.), The Global Transformations Reader (pp. 311-334). Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. 12. Castles, S. (2000). International Migration at the Beginining of the Twenty-First Century: Global Trends and Issues. International Social Science Journal, 52(165), 269-281. doi: 10.1111/1468-2451.00258 13. Castles, S. (2013). The Forces Driving Global Migration. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 34(2), 122-140. 14. Coates, J. (2003). Ecology and Social Work: Towards a New Paradigm. Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing. 15. Cohen, R. (2006). Migration and its Enemies: Global Capital, Migrant Labour and the Nation-state. Aldershot: Ashgate. 16. Cornwall, A. (2008). Unpacking ‘Participation’: models, meanings and practices. Community Development Journal, 43(3), 269–283. 17. Cottle, S. (2006). Mediatized Conflict. Maidenhead, England: Open University Press. 18. Crawford, C. (2003). Towards a Common Approach to Thinking about and Measuring Social Inclusion Draft (pp. 1-18). Canada: Roeher Institute. 19. Cross, T. L., Bazron, B. J., Dennis, K. W., & Isaacs, M. I. (1989). Towards a culturally competent system of care. Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Chid Development Centre. 20. Demeny, P. (2002). PROSPECTS FOR INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION: GLOBALIZATION AND ITS DISCONTENTS. Journal of Population Research, 19(1), 65-74. doi: 10.2307/41110739 21. Doherty, T. J., & Clayton, S. (2011). The Psychological Impacts of Global Climate Change. American Psychologist, 66(4), 265–276. doi: 10.1037/a0023141 22. Dominelli, L. (2010). Globalization, contemporary challenges and social work practice. International Social Work, 53(5), 599-612. 23. Esipova, N., Pugliese, A., & Ray, J. (2013). The demographics of global internal migration. Migration Policy Practice, 3(2), 3-5. 24. Fitzgerald, M. H., Mullavey-O’bryne, C., & Clemson, L. (1997). Cultural issues from practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 44, 1-22. 25. Forde, C., & Lynch, D. (2013). Critical Practice for Challenging Times: Social Workers’ Engagement with Community Work. British Journal of Social Work, 1-17. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bct091 26. Gopalkrishnan, N. (2003). Seeing the Elephant: The Tale of Globalisation and Community Development. New Community Quarterly, 1(2), 20-23. 27. Gopalkrishnan, N. (2006). Rethinking Child Protection: Issues of Cultural Competence. Paper presented at the National Conference on Multicultural Families: Investing in the Nation’s Future, Maroochydore. 28. Gopalkrishnan, N. (2008). Anti-Racist Cultural Competence: Challenges for Human Service Organizations. In H. Babacan & N. Gopalkrishnan (Eds.), The Complexities of Racism: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on “Racisms in the New World Order”. Qld.: University of the Sunshine Coast. 29. Gopalkrishnan, N. (2013). India: A Country Report. In H. Babacan & P. Hermann (Eds.), Nation state and Ethnic Diversity. New York: Nova Science Publishing. 30. Gow, K. M. (1999). Cross-cultural Competencies for Counsellors in Australasia. Paper presented at the Culture, Race and Community Conference, Melbourne. 31. Graf, A. (2004). Assessing intercultural training designs. Journal of European Industrial Training, 28(2/3/4), 199-214. 32. Hage, G. (2002). Arab Australians Today: Citizenship and Belonging. Carlton South: Melbourne University Press. 33. Harmes, A. (2006). Neoliberalism and multilevel governance. Review of International Political Economy, 13(5), 725-749. doi: 10.1080/09692290600950621 34. Haskett, M. E., Scott, S. S., Nears, K., & Grimmett, M. A. (2008). Lessons from Katrina: Disaster Mental Health Service in the Gulf Coast Region. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39, 93–99. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.1.93 35. Held, D. (2010). Cosmopolitanism: Ideas, Realities and Deficits. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. 36. Held, D., & McGrew, A. (2002). Globalization/Anti-Globalization. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. 37. Heron, T. (2008). Globalization, Neoliberalism and the Exercise of Human Agency. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 20(1), 85-101. doi: 10.1007/s10767-007-9019-z 38. Hollinsworth, D. (2006). Race and Racism in Australia. South Melbourne: Thomson. 39. Ife, J., & Tesoriero, F. (2006). Community Development: Community Based Alternatives in an Age of Globalisation (3 ed.). Frenchs Forest: Pearson Education Australia. 40. IOM. (2011). World Migration Report 2011. Geneva: International Organization for Migration. 41. Ivey, A. E., Ivey, M. B., & Zalaquett, C. P. (2010). Intentional Interviewing and Counseling: Facilitating Client Development in a Multicultural Society. Boston: Cengage Learning. 42. Kenny, S. (2011a). Developing Communities for the Future. South Melbourne: Cengage Learning. 43. Kenny, S. (2011b). Towards unsettling community development. Community Development Journal, 46(suppl 1), i7-i19. 44. Landis, D. (2008). Globalization, migration into urban centers, and cross-cultural training. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 32, 337-348. 45. Ledwith, M. (2001). Community work as critical pedagogy: re-envisioning Freire and Gramsci. Community Development Journal, 36(3), 171-182. 46. Lum, D. (1999). Culturally competent practice: A framework for growth and action. Pacific Grove CA: Brooks/Cole. 47. Mansuri, G., & Rao, V. (2004). Community-Based and -Driven Development: A Critical Review. The World Bank Research Observer, 19(1), 1-39. doi: 10.2307/3986491 48. Martin, H., & Schumann, H. (1997). The Global Trap: Globalization and the assault on prosperity and democracy. New York: Zed Books Ltd. 49. Mendes, P. (2003). Australia’s Welfare Wars. The Players, the Politics and the Ideologies. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press. 50. NHRMC. (2006). Cultural Competency in Health: A Guide for Policy, Partnerships and Participation Retrieved 16/11/2010, 2010, from http://www.nhmrc.gov.au 51. Nybell, M. L., & Gray, S. S. (2004). Race, Place, Space: meanings of Cultural Competence in Three Child Welfare Agencies. Social Work, 49(1), 17-26. 52. OADBS. (2012). INDIA: Internal migration trends portend new risks (pp. 1-n/a). Oxford: Oxford Analytica Ltd. 53. Putnam, R. D. (2007). E Pluribus Unum : Diversity and Community in the Twenty-first Century: The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian Political Studies, 30(2), 137-174. 54. Quinn, M. (2003). Immigrants and Refugees: Towards Anti-Racist and Culturally Affirming Practices. In J. Allan, B. Pease & L. Briskman (Eds.), Critical Social Work: An Introduction to Theories and Practices. Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin. 55. Solimano, A. (2010). International Migration in the Age of Crisis and Globalization : Historical and Recent Experiences Retrieved from http://jcu.eblib.com.au/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=542896 56. Soros, G. (2002). George Soros On Globalization. New York: PublicAffairs. 57. Stiglitz, J. (2002). Globalization and its Discontents. London: Penguin Books. 58. Turner, B. S., & Khondker, H. H. (2010). Globalization East and West Retrieved from http://jcu.eblib.com.au/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=537763 59. UNHCR. (2011). UNHCR Statistical Yearbook. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 60. UNICEF. (2012). Overview of Internal Migration in India Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/india/1_Overview_%2803-12-2012%29.pdf Narayan Gopalkrishnan Dr Narayan Gopalkrishnan teaches Social Work at James Cook University, Australia. narayan.gopalkrishnan@jcu.edu.au |

Categories

All

Social Work Learning Academy50,000 HR PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS. MHR LEARNING ACADEMYGet it on Google Play store

|

SITE MAP

SiteTRAININGJOB |

HR SERVICESOTHER SERVICESnIRATHANKA CITIZENS CONNECT |

NIRATHANKAPOSHOUR OTHER WEBSITESSubscribe |

MHR LEARNING ACADEMY

50,000 HR AND SOCIAL WORK PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed