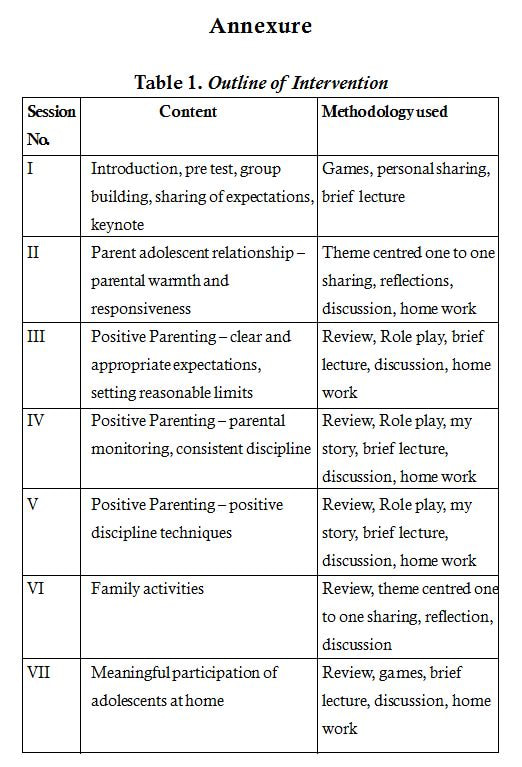

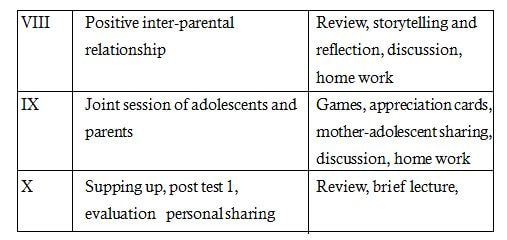

Changing Family Context and Adolescent Wellbeing: Relevance of FamilySocial Work Interventions12/23/2018 Abstract Adolescence is a transition period where adolescent children become increasingly independent from their families but the existing literature reiterates that family is central to the healthy development and transition of adolescents. But, adolescents as well as the families today, are in a fast paced changing society which significantly influences both. The changes in the society not only pose a threat to family as a primary social environment for human development but also present demands on it to function better. In this article, the authors take a closer look at the demands and challenges of the family context today and analyses the effect of a social work family intervention for strengthening family as a critical context for healthy adolescent development. Keywords: Family context, adolescent well being, family strengths, family intervention. Introduction Family is regarded as the primary social system in a society. Family is also traditionally considered as the primary socializing agency for children and adolescents which were effective instruments in preparing young people as responsible citizens. A healthy family, thus, is crucial for developing a healthy society. This has been reiterated by the background report of United Nations on trends affecting families, which states that family is an institution which resolves or eases a large number of social problems (UN, 2006). The literature of the last two decades explicitly shows this increasing recognition of the significance of family today (Moore, Lippman and McIntosh, 2009, Benard, 2006, Zarret et al., 2008). One reason for the renewed interest in family could be the rising problems among children and adolescents. After a systematic review of literature on mental health issues of children and adolescents in 21st century, William Bor and colleagues reported that internalizing symptoms are increasing among children and adolescents suggesting prevention and early intervention approaches (Bor et al, 2014). Mental health practitioners and public health researchers also acknowledge the increase in problems due to the deteriorating indices of the adjustment of children and young people, in response to social and family changes (Fukuyama 2000 cited by Vimpani G. et al., 2002). The World Health Organisation, after reviewing the mental health programmes in different countries strongly recommends mental health promotion and prevention of mental disorders among children and adolescents (WHO, 2008). Family Context and Adolescent Wellbeing The resilience researches clearly show that family is a critical protective factor in the well being of adolescents providing a secure base characterized by caring relationships, feeling of connectedness, support etc (Benard, 2006; Robinson et al., 2011). According to Santrock, family provides a positive support system for young people to explore their changing identity (Santrock, J.W. 2014, cited in Sacks, V et al, 2014). A longitudinal study among the US adolescents reported that adolescents who felt highly valued and were able to confide in family members at age 15 had substantially reduced risks for mental illness at age 30 (Paradis et al., 2011). Researches also shows that the role of a supportive adult, through quality time and warm communication, provided by the parent is regarded as highly beneficial for adolescents in resolving their conflicts and successfully moving into adulthood (Vassallo et al, 2009). They also found that the support offered by the parents was highly valued by the young people. Family as a social system also serves as a protective factor for healthy adolescent development. Researchers of the national level longitudinal 4-H study on positive youth development in U.S. after examining an array of assets within the family, school, and neighborhood of adolescents found that eating dinner together as a family was one of the most important factors associated with positive adolescent development. They also found that this collective activity among family members was the strongest predictor of positive adolescent functioning, irrespective of the influence of sex, race, and family household income (Zarret et al., 2008). Joint activities of parents and children during adolescence have much more far reaching positive effects on healthy adolescent development like fostering autonomy, skill development, conflict resolution and team work in addition to the improved relationships. Changing Family Context Families, as fundamental unit of a society, have been significantly affected by the rampant socio economic and technological changes today. Apart from the structural changes, families are also affected by the stabilized changes in the functioning of families. Increased participation of women in workforce is one such prominent change, the effects of which is exacerbated by the longer working hours, highly demanding jobs of both spouses. The overturned priorities and lack of quality time with children coupled with poor parenting skills and inadequate social support system makes parenting and family life exhaustive and too demanding. The extensive non moderated media exposure has also resulted in reorientation of social values and changing life styles. Families are being exposed to wider and attractive choices with fewer stigmas attached. One of the dangerous emerging trends in modern families is the shrinking of families within the households, with less social and intra family relationships. Today’s family life became much more home centered (UN, 2006), rather TV centered or room centered which does not foster interaction among the members, otherwise consciously attempted. The ever increasing rates of divorce, child maltreatment and violence at home are evidences for the imbalances our families are facing under these multiple pressures. Though inversely affected by these challenges, families have never been considered as those in need of support in effective functioning. Parents especially need help since they are the primary persons performing the functions of a family and thereby sandwiched between the demands. Just like children need help in nurture and protection, parents also need support in order to fulfill their adult roles in the family (Hobbs et al, 1984 cited in Dunst et al, 1994). As natural settings for promoting well being of children and adolescents families need to be helped to recognize the strengths or protective factors inherent in them and nurture them so that it helps in enhancing the wellbeing of both the family as a whole and its individual members, especially the children. Strengthening Families for enhancing Adolescent Well Being Family is by far the most enduring and central institution in society throughout human history. It is a dynamic system with evolving capacities in response to the constant demands placed on it. A vast majority of our children and adolescents are successfully growing into responsible and productive adults itself is a clear evidence of this wonderful ability of family. Public health and social science researchers who were working on child and family problems for a long time has now shifted their focus to promoting positive development of children within the families and neighbourhood (Moore et al, 2009). Existing evidence also shows that adolescent-parent attachment is a determinant of health during the developmental period and point towards the need of support required by the parents of adolescents in facilitating the transition of their children through adolescence and keeping them connected to the family (Moretti et al, 2004). Family strengthening interventions with a strengths focus are based on the perspective of environmental strengths and supports which are fostered to enhance both family and adolescent well being. This is based on the growing evidence that it is the positive factors within and in the immediate environment of adolescents that are predictive of better outcomes in them (Zirpoli, 2005, Gottfredson, 2001). This approach is supported by an increasing body of research on families, schools, and neighborhoods as a cutting-edge approach for enhancing adolescent development, and for helping youth reach their full potential (Zarret et al., 2008). The basic foundation of this approach is the fundamental belief that children and families have unique talents and skills and that they are resourceful in dealing with their problems which can be tapped from their own life events and previous experiences. Hence the emphasis is on what works in a family so that they could be replicated in strengthening the family. The present study was done with the objective of finding the effectiveness of a social work family intervention focusing on family strengths in families with adolescents. Overview of Intervention The intervention made use of social group work techniques and skills with a firm belief in the inherent strengths in the adolescents, parents and family as a social system. The intervention package comprised of ten weekly sessions of two hours each for mothers including one joint session of adolescents and mothers. The methodology of the intervention was designed in such a way to promote collaborative practice with the mothers and made use of group as a mutual aid system in enhancing the strengths. Mothers’ experiences in dealing with their adolescent children were highly valued and discussion was a dominant method used in eliciting their views, experiences and expertise. Every session began with a review of the practice of family strength discussed in the previous session and ended with a home assignment related to the particular family strength discussed in the session. The methodology included role play; theme centred one to one interaction, games, sharing of previous success stories, positive reframing, appreciate and supportive inquiry and discussions. The mothers were given space for adding value to the programme through their suggestions, which they effectively used. An overview of the content of the intervention is given in Table 1. Method The researcher used a one group pre-test post-test pre experimental design without control group for conducting the study. The intervention was conducted as a school based programme where parents from similar socio economic background have easy access to, and acceptance of the programme. After having initial briefing sessions with all the students studying in 8th and 9th standards in the school and their parents, twenty adolescents and their mothers who expressed willingness to be part of the intervention by setting apart twenty hours were included in the intervention programme. Out of the 20 families who registered for the intervention programme, 16 families including 16 mothers and their adolescent children who successfully completed the ten intervention sessions (spread along two and a half months) were taken as the experimental group for the research. Four mothers who could not attend two to three sessions due to personal inconvenience were omitted from the study, though they participated in the rest of the sessions. Measures Quantitative data on four family strengths; positive parenting, family activities, adolescent participation in family and parent adolescent relationship were collected from the participant mothers before and after the intervention using self administered tools. The tool consisted of the following measures,

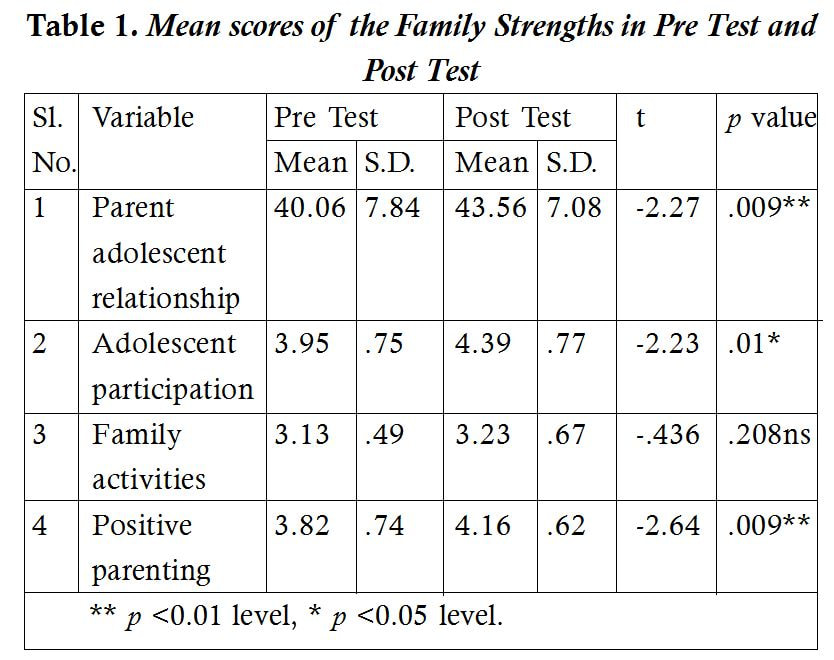

Analysis of the quantitative data was performed by utilizing SPSS 17.0 and the qualitative data was analysed using manifest content analysis. The effectiveness of the intervention on the participant families was done by comparing the pre test and post test mean values of the family strengths using dependent T test. The researcher also did a comparative analysis of the distribution of the participant families along the different levels of family strengths. Findings The participant group consisted of 16 parents, all of whom were mothers; and their 16 adolescent children. Out of 16 adolescents, eight were males and the remaining eight were females. The mean age of the adolescents was 13.3. Twelve out of the 16 families were Christians, three were Hindus and one family belonged to Muslim community. The mean age of the mothers was 38.9. The mean duration of married life of the parents was 16.18 years. The median education level of the mothers was higher secondary level. The mean differences in three test variables, parent adolescent relationship, adolescent participation and positive parenting were found statistically significant (see Table 2) which means that there was a significant change in those family strengths after the intervention. Family activities did not show any significant change after the intervention. The researcher also compared the frequency distribution of the participant mothers with respect to the different levels (very high, high, moderate and low levels) of the family strengths. It was found that the number of families with very high level of parent adolescent relationship was doubled after the intervention, due to the upward movement of the families from the lower levels. Among the 16 participant families, there was not a single family having very high level of family activities before the intervention. But three families moved up from high level to a very high level of family activities after the intervention. The number of families having moderate level of family activities remained the same, after the intervention. Regarding the increase in family activities in different areas, though changes were visible in all eight areas investigated; playing together (both indoor and outdoor play) became the area with considerably high increase after the intervention, which was the area with the least joint activity during pre test. Regarding adolescent participation in family, half of the participant families were having moderately low level of adolescent participation in their families before the intervention while it was changed to moderately high level of participation in seven families after the intervention. The number of families with high level of participation was also doubled after the intervention. But, the number of families with low level of adolescent participation remained the same throughout the period. The researcher also compared the meaningful participation of the adolescents in family matters before and after the intervention. This comprised of the moderately low level to very high levels of adolescent participation where adolescent opinions are sought, considered and even have joint decision making. The highest increase in meaningful participation of the adolescent occurred in the area of family rules where six families in the pre test was increased to eleven families after the intervention, which was the area with the least meaningful participation during pre test. This was followed by family budget and expenditure and recreational activities. On comparing the number of families in different levels of positive parenting before and after the intervention showed that those who fall in the category of very high level of positive parenting was increased from seven to nine, those who fall in the high level of positive parenting was also increased from five to seven families while there were no families in the moderate level of positive parenting, after the intervention. This finding was complemented with the high increase in adolescent participation in family rules and also the increase in the different dimensions of parent adolescent relationship. Findings from Qualitative Data The manifest content analysis of the qualitative data elicited from the adolescent children revealed three themes evident in the expressions used by the adolescents. The themes were, 1. Parental warmth and understanding: All 16 adolescents reported that their mothers became more responsive to them and were spending time with them. They also expressed their happiness in the changes they observed in their mothers. The expression used by majority of adolescents was ‘caring’. Some of them used the word ‘understanding’ in describing the change they felt in their mothers’ behavior. One adolescent used the phrase, ‘I got more love’ while another adolescent used the expression ‘friendliness’ in describing the change. Some of the adolescents also said that their mothers became more appreciative of them and had become calmer in their mutual interactions. This might be because of the mutual understanding developed between the mother and the adolescent through open communication during the time they spent together. This is again indicated by another excerpt which expressed better communication between the mother and adolescent, which in turn, led to fewer conflicts between them. Some of the excerpts are, Excerpt 1:”Some changes are there, mom is more caring now, spends more time with me, we celebrated Christmas together, felt more close to each other. I also am caring my father and mother more”. Excerpt 2: “More communication is there now; my home is more peaceful now” 2. Reciprocal Changes in Adolescents: All the expressions elicited from the adolescents denoted a reciprocal change in the adolescent behavior in response to the changes they observed in their mothers. Some of the adolescents said that they started caring their parents more while one adolescent expressed that he started thinking along with his parents while another adolescent said she now feels for her mother. Majority of the adolescents reported that they have their usual behavior and responses at home. They started joining their mothers in household tasks voluntarily. One adolescent also reported that he had his anger outbursts reduced. Some of the excerpts are, Excerpt 3: “We sat and talked with each other, my parents are caring me more, spend more time with me. I join in household tasks. When I got more love I also care them more” Excerpt 4: “I started thinking positive, I’m doing things which are appreciated, I started praying and helping parents. It was a special programme” According to Lamanna and Reidmann, the sense of respect that grows out of mutual acceptance contributes to better parent child relationships and improved self images for both parents and children (Lamanna & Reidmann, 1988). The adolescent expressions on change in their thinking and behavior could possibly have resulted out of this improved parent child relationships. This also shows that parents can influence adolescent’s behavior positively. Adolescents want to be cared for, to be listened to and be valued as a young adult. A responsive and supportive parent is a strong protective factor in the life of an adolescent. When parents make positive attributions to their children…..children internalize them (Laing, 1971 cited in Lamanna & Reidmann, 1988). 3. Joint activities: Another important outcome as reported by the adolescents was the increased joint activities of parents and adolescents. Many adolescents reported of having joint activities with all family members which they enjoyed well. Some of the excerpts also showed that the fathers who did not participate in the intervention were also positively influenced indirectly by the programme. Some of the excerpts are, Excerpt 5: “I enjoyed the programme, papa now takes us together for outing” Excerpt 6: ”There are changes in my parents’ behavior, they are not blaming me now, became more loving. We prepared food together for Christmas and celebrated well. I understood my mother’s difficulties, feel more obedience and love for my mother” Discussion The study was undertaken by the researcher to find out whether strength based social work interventions in a group of families would result in enhancement of family better well being of families and adolescents. The findings clearly show that the family strengths, parent adolescent relationship, positive parenting and adolescent participation in family were significantly improved. The findings go well with the existing literature on family strengths and adolescent well being. The multi cultural study done by Phinney and Ong on adolescents, after controlling socio economic status, gender, and cohort, found that the main effect of adolescent-parent relationship on life satisfaction was significant (Phinney & Ong, 2002). Another correlational study conducted in Kerala itself reported that parent adolescent relationship and positive parenting were significant predictors of adolescent well being (Thomas & Joseph, 2015). The present findings are more significant since the intervention was done in a general non clinical group in which all the family strengths (except adolescent participation) were reported to be high before the intervention. This is again confirmed by the findings on the ascending changes in the distribution of families along the different levels of the family strengths. In the case of all four family strengths, those parents who were in the high level moved up to very high level after the intervention, those in the moderate level moved up to either high or very high level and some families in the lower level moved up to moderate or high level. This shows that, irrespective of the situations, strengths based interventions are helpful for families to enhance their level of family strengths. This reveals the utility of strength based interventions, with less stigma attached, as universal level or developmental interventions to promote or enhance adolescent and family well being. Parents are willing and wanting to get help in becoming better and effective parents provided there are fewer stigmas attached to it. Such universal interventions conducting as school based programmes increases its attractiveness and acceptability among parents (Shek, 2004). But, it should also be noted that though the number of families in the low level of family strengths became nil or reduced, one or two families remained in the low level category even after the intervention. Since the participant group was taken from a general population without any inclusion criteria, these families could be those which require additional help so that they could experience the benefit of the intervention. In such situations, the intervention programme can also be a screening platform for identifying families and children at risk so that they could be further helped through other individualized strengths based services. An evaluation of the modality of the study highlights the importance of the language of strengths, as experienced by the researcher and the participant families. The continued focus on strengths helped the parents to be active participants in the programme. Change becomes possible through the identification of the system’s strengths (Germain, 1991). The strengths focus might also be the reason for the positive adolescent outcomes as reciprocal changes in the adolescent behavior, as revealed from the qualitative data. This is very much in congruence with the ecological systems perspective in which the nature of relationships between systems is seen as reciprocal exchanges between entities in which each entity changes or otherwise influences the other (Germain, 1991). The data also showed some evidence of positive reciprocal changes occurred in the fathers of adolescents, who were not part of the programme. Greene and colleagues (2005) describe this language of strengths and empowerment in terms of the languages of collaboration, ownership, possibilities, solution, elaboration and clarification. This include positive reframing, helping clients to look up towards identifying, amplifying, and reinforcing their existing strengths and resources and also helping them to broaden their view of the resources and options they have and rediscover the strengths which are either forgotten or never used (Greene et al, 2000 cited in Greene et al, 2005). This was found particularly useful in getting parents active collaborators of the programme, who themselves were following up each other to come for each subsequent sessions. The conduct of the programme as a group intervention also helped in getting active response of the parents. The feedback from the participant mothers clearly point to the benefit of group as a mutual aid system in experiencing multiple helping relationships, accelerating the changes in them, building confidence in them and finally building sustained network of relationships among the mothers. Several mothers reported of the benefit of these relationships with other participant mothers in monitoring their adolescent children. Since the study lacked a control group for comparison the findings need to be validated by subsequent studies using control groups. Even then the study was useful in highlighting the need to look into the utility of family interventions for enhancing adolescent well being, which are explicitly strength based and are school based interventions. Another limitation of the study was the length of the intervention. The participant parents of the programme also suggested the intervention to be conducted in brief mode consisting of two days, in which both parents can take part without much difficulty. But, the effectiveness of such brief model need to be explored and experimented since the weekly sessions helped parents to go and try out what they have discovered and then return to the subsequent session with their feedback. This sort of reflection-action-review process may be difficult in brief sessions. Conclusion Family, as an external asset is a significant context for healthy adolescent development. Hence, families need to be acknowledged and utilized in promoting adolescent well being, rather than investing in treatment of adolescent issues. The study on strength based family social work intervention for enhancing adolescent well being was done to understand the possibilities of having universal or developmental interventions for promoting adolescent well being utilizing the strengths of their natural developmental context. The study has brought to light the need for such interventions as well as the far reaching effects of strengths focus in developmental/ primary prevention interventions. References

Nycil Romis Thomas, MSW, PhD,

Asst. Professor, Department of Social Work, Rajagiri College of Social Sciences, Rajagiri P. O., Kochi, Kerala. Mary Venus Joseph, MA(SW), PhD Dean (Research), Rajagiri College of Social Sciences, Kochi, Rajagiri P. O., Kochi, Kerala. |

Categories

All

Social Work Learning Academy50,000 HR PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS. MHR LEARNING ACADEMYGet it on Google Play store

|

SITE MAP

SiteTRAININGJOB |

HR SERVICESOTHER SERVICESnIRATHANKA CITIZENS CONNECT |

NIRATHANKAPOSHOUR OTHER WEBSITESSubscribe |

MHR LEARNING ACADEMY

50,000 HR AND SOCIAL WORK PROFESSIONALS ARE CONNECTED THROUGH OUR NIRATHANKA HR GROUPS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

YOU CAN ALSO JOIN AND PARTICIPATE IN OUR GROUP DISCUSSIONS.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed